Nicole Kidman: David Thomson’s plaything

David Thomson, or “David Thomson”? Critic or stalker?

David Thomson is often described as a “film critic,” but film criticism is not quite what he does. Nor is he a journalist or a biographer or a historian by any traditional definition of those terms. Thomson is a cinephile, a fantasist and an autobiographer, who writes about movies — and the characters in them, and the people who make them — as his possessions, imagined aspects of himself.

In the introduction to his best-known book, the idiosyncratic and provocative “A Biographical Dictionary of Film,” he admits that, in writing about movies, he is unavoidably writing about himself — and, indeed, the book might be better titled “An Autobiographical Dictionary of Film.” All film criticism (and all writing, fiction or “non-fiction”) is to some degree autobiographical, and Thomson has been more aggressive and up-front about his obsessions with his fantasy-objects, from Warren Beatty to Nicole Kidman, than most. But I’m not sure his treatment, or imaginative possession (sexual and otherwise), of his not-at-all-obscure objects of desire is any less tabloid-creepy because it is presented as critical nonfiction rather than as gossip or on some fanatical fan blog, except that Thomson’s writing is better.

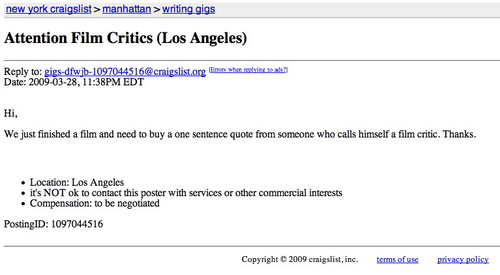

Last week, Kidman’s reps said Thomson had misrepresented himself in the one telephone interview he did with Kidman for his ostensible biography, being sold under the title “Nicole Kidman.” From The Daily Mail:

According to the star’s publicist Wendy Day: “Nicole has never met David Thomson. She has only spoken to him briefly on the phone about her acting processes and various films.

“He’s a well-respected film writer and she accepted the interview only because she was under the impression he was writing a series of film essays.”

So, if Thomson is going to write about movie-fed fantasies, and he’s decided to focus his on Nicole Kidman, what are his ethical responsibilities when it comes to soliticiting her unknowing cooperation in his enterprise? A review in the New York Times, which calls the ostensible biography “a weird and unseemly mash note,” offers several quotes from the book, including:“I should own up straightaway that, yes, I like Nicole Kidman very much. I suspect she is as fragrant as spring, as ripe as summer, as sad as autumn and as coldly possessed as winter…. That’s why I’m writing this book, I think, to honor desire.”

“Just as I take the breakup with Cruise as the liberating and altering experience in Kidman’s life, so we have to see that Tom was changed, too.”

“I dare say she wakes up some nights screaming because she felt it [aging, losing her looks] was about to happen. (Not that I can be there to witness it — or stop imagining it.)��?

Thomson also speculates about what might have happened on the set of “Eyes Wide Shut,” in this excerpt from the book published in the Sunday Times of London: