“It goes on and on and on and on…”

It was 1991 and we were talking about “Barton Fink”:

Joel Coen: … I also don’t think it’s as difficult as some people think it is. I mean, some people come out going, ‘I don’t get it.’ And I don’t quite know what they’re trying to ‘get,’ what they’re struggling for.

Ethan Coen: It’s a weird story, but it’s a fairly straightforward story that I think can be enjoyed on its own terms… ‘Barton Fink’ does end up telling you what’s going on to the extent that it’s important to know — you know what I mean? What isn’t crystal clear isn’t intended to become crystal clear, and it’s fine to leave it at that.

Joel Coen: But we have had the reaction where people leave the movie sort of uncomfortable and befuddled because of that. Although that wasn’t our intention to do that. I was going to say that maybe our telling of the story wasn’t as clear as it should have been, but I don’t think that’s true. In terms of understanding the story, it comes across.

The question is: Where would it get you if something that’s a little bit ambiguous in the movie is made clear? It doesn’t get you anywhere.

Where would it get you? That’s what I was thinking about after the “Sopranos” finale last night, and I remembered this conversation. What if Barton had opened the box? What then? I’ve mentioned the ways “The Sopranos” has paid tribute to the Coens’ “Miller’s Crossing” (particularly in “Pine Barrens,” the whacking of Adriana, the lawyer named Mink), right down to the ambiguous (and perfect) ending. Which is also in the spirit of “Barton Fink.” I can’t imagine anything more true to the show, or more dramatically satisfying, than what happened Sunday night. (I’m also reminded of those who were desperate to know, once and for all, if Julia Sweeney’s Pat character on “SNL” was a man or a woman — when it was perfectly obvious that the whole conception of the character was that there was no answer to that question. The question is the character. That’s not only the joke, it’s the punchline.)

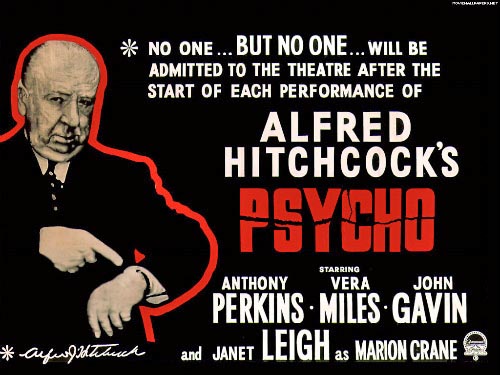

What if you could open this? Then what?

So, for those who wanted to “know what happened” in Episode 86 of “The Sopranos” (and apparently there are lots of them — evidently casual “fans” of the show who haven’t been paying any attention to what it’s about for eight years), I have to ask: What did you want? If any or all of the things you expected happened, then where would that get you?

Series creator David Chase obviously knew that if he provided one or more of the usual denouements, it would color everything that came before. So, Tony gets his comeuppance, by getting whacked, or losing family members, or going to jail, or going into the Witness Protection Program like that schmuck Henry Hill in “GoodFellas.” Aha! That’s what this has all been leading up to! What could be more anti-climactic than any of those trite outcomes? You’ve seen them all before in other movies, anyway. To me, they would have spoiled “The Sopranos” by arbitrarily assigning it a hackneyed and finite “moral lesson” end-point.

“The Sopranos” has always been founded on the proposition that human nature, character arcs (Christopher: “Where is my arc?!?!”) and narrative structures are roughly the shape of… I don’t know, onion rings. People have breakthroughs, illuminations (Tony: “I get it!”), vow to change their ways, think they have changed… and then fall back into their old ways. Because that, fundamentally, is who they are.

AJ winds up being the same spoiled brat he was in Season One. Meadow continues to be the mildly rebellious princess (and she’s the only one in the house who seems to unambiguously acknowledge and even accept what Tony does for a living — hence her not-so-subtle dig at her father about why she wants to become a lawyer), but within bounds that will still win parental approval. Christopher straightens out, and then relapses. Carmella leaves Tony on principle, and then succumbs to the same old pattern of denial and expensive kickbacks that formed the basis of her marriage from the beginning. Dr. Melfi convinces herself that she’s helping Tony, and then dumps him in an unprofessional huff when publicly exposed, simply because she got “caught,” as if she were one of his mistresses. Tony the sympathetic sociopath learns to blame everything on his mother as his latest way to avoid reforming or taking any responsibility for his own behavior… Will the circle be unbroken? No way.

Remember Charles Foster Kane. Thompson, the reporter (William Alland), gives his eloquent speech: “Mr. Kane was a man who got everything he wanted and then lost it. Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn’t get, or something he lost. Anyway, it wouldn’t have explained anything… I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life. No, I guess Rosebud is just a… piece in a jigsaw puzzle… a missing piece.” And then, in the final seconds, we discover what “Rosebud” is, even if nobody in the movie ever does. And where does that get you? The real ending of “Citizen Kane” is Thompson’s speech. The revelation of “Rosebud” is great showmanship, the final piece of the jigsaw puzzle, all right, but it doesn’t really explain anything we didn’t already know.

So, I ask you again: Whaddaya want?

www.neomyz.com/poll

Create your own web poll in less than 3 minutes,

and gain valuable feedback from your site visitors.

Your browser does not seem to support JavaScript,

the poll will not be displayed.

December 14, 2012