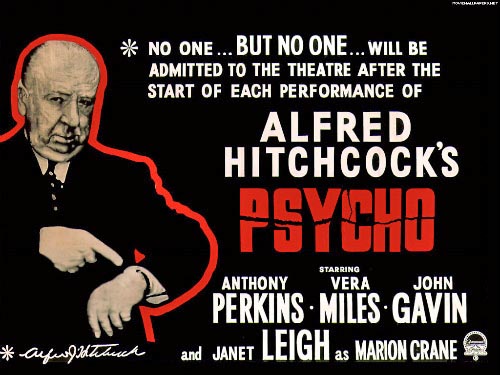

I grew up in a time (the 1960s and 1970s) when commercial, technological and artistic conventions accustomed us to listening to music on LPs and watching movies in theaters. For the most part, we listened to one side of an album at a time (eventually, CDs — although more easily programmable — would play 70+ minutes of uninterrupted music, which changed song-sequencing priorities). And we saw movies from start to finish. I’m too young to remember the original ad campaign for Alfred Hitchcock‘s “Psycho” (1960), but later on (when I got my hands on some original lobby cards — those were the 11″x14″ images displayed with the posters at the entrances or in the lobbies of theaters) I noticed it was built around the apparently novel pitch that audiences had to see the movie from the start.

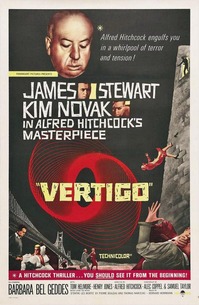

Now, if, like me, you were in college (or university, as they say back East) when Alvy Singer (Woody Allen) in “Annie Hall” announced that he had to see a picture “exactly from the start to the finish,” and you thought that made perfect sense, it seemed bizarre to imagine a time when people had to be encouraged to show up before the feature started: “No one… BUT NO ONE… will be admitted to the theatre after the start of each performance…” (It turns out Paramount had done something similar with Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” just two years earlier: “It’s a Hitchcock thriller… You should see it from the beginning!”) As the proprietor of the Opening Shot Project, which emphasizes the importance of the first shot in setting up and framing certain films, the idea that somebody would watch a movie without having seen the beginning is incomprehensible to me. Why cheat yourself of the joys of discovery and development? Or just knowing what’s going on in the story?

“It is required that you see PSYCHO from the very beginning! The manager of this theater has been instructed, at the risk of his life, not to admit to the theatre any persons after the picture starts.

“Any spurious attempts to enter by side doors, fire escapes, or ventilating ducts will be met by force.

“The entire objective of this extraordinary policy, of course, is to help you enjoy PSYCHO more.”

— Alfred Hitchcock

I think I remember one time when my mom dropped off me and my friends at the budget Lynn Twin theater in the middle of a matinee showing of “Call Me Bwana” (Gordon Douglas, 1963 — must’ve been a re-release) with Bob Hope and Anita Eckberg, which was playing on a double-feature with “Beau Geste” (Doublas Heyes, 1966), with Guy Stockwell, Doug McClure and Leslie Nielsen. But that was a Saturday kiddie matinee, and we all knew it was just a form of weekend daycare. (Incidentally, I thought the Bob Hope movie was terrible — though not as painful for me to sit through as Stanley Kramer’s 1963 “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World,” which also had me cringing and grinding my teeth as a kid.)

For years I’ve heard that it was commonplace in earlier decades for people to simply “go to the movies” — no matter what was playing, or what time it was showing. In my attempts to learn more about this strange ritual from a bygone era, I came across this essay by Gary Cokins on the origin of the phrase, “This is where we came in.” Mr. Cokin writes:

If you are old enough, you will recall this phrase when you went to the movies in the 1950s. That was when during the double-feature era before 1960, movie theatres did not list show times in newspapers. If they did, few paid attention to them. You just showed up and entered the dark theatre while one of the movies was playing. You would wait a few seconds for your eyes to adjust to the dark and then shuffle to empty seats. A few hours later came that memorable moment when you or one of your companions would nudge the others and say, “This is where we came in.” Then you’d shuffle out.

This was common. You were not the only ones. It was an ingrained habit to arrive at any old time. Others who came in at some other time did the same thing. People were continuously entering and leaving the theatre. How could we understand the movie’s plot while watching it beginning at some scene in the middle on to the end, and then from the beginning to the middle? It now seems crazy but our brains seemed to do mental splicing that did not require much effort. But we really lost something in the experience. When you saw the ending prior to the beginning, you did not gain from the introductory set up of the plot and the characters.

I don’t know how accurate this is (and I’m still looking into it, because it’s bugged me for a long time), but Mr. Cokin (I use the courtesy title because in the picture accompanying his column he looks like he should be addressed that way) says the practice ended with Hitchcock and “Psycho.” Can this be true?

I was born in 1957, the age of Sputnik and rock ‘n’ roll on 45 rpm records. Rock was a singles medium until the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967) definitively shifted peoples’ thinking about LPs as something more than a collection of discrete songs, singles and “album tracks” (songs that were deemed to have no hit potential). The iPod and downloadable music formats have put the emphasis back on singles again — just as, I suppose, the repeatability and non-linear capacities of DVDs can bring back something of the “This is where we came in…” experience. You can start somewhere in the middle and watch to the end (whether that’s your original intention or not), then start over again from the beginning, if you like. [As others point out in comments below, repeat showings of movies on cable also have this effect.]

If anyone else has information about, or memories of, this bygone audience behavior, please let me know….