Scanners

Skyfall: Hey kids, let’s put on a show!

“Skyfall” is a theatrical film in the same way that its director, Sam Mendes, is a theatrical filmmaker. That is, its approach to organizing space for an audience (the camera lens) is noticeably stagey. I mean that in a “value-neutral” way. I just mean the frame is frequently used as a proscenium and the images are action-tableaux deployed for a crowd — whether it’s the designated audience surrogates in the movie (bystanders or designated dramatis personae), or the viewers in the seats with the cup-holders. That’s not to say it’s uncinematic (it’s photographed by the great Roger Deakins!), but many of the set-pieces in “Skyfall” are conceived and presented as staged performance pieces.

Stop thinking! Why don’t you just enjoy it?

From Roger Ebert @ebertchicago: “To people who say ‘Just enjoy! Don’t analyze!’ This speaks eloquently for me.” From Racialicious via io9 (“When Will White People Stop Making Movies Like ‘Avatar’?”):

Of all the varieties of irritating comment out there, the absolute most annoying has to be “Why can’t you just watch the movie for what it is??? Why can’t you just enjoy it? Why do you have to analyze it???” […]

First of all, when we analyze art, when we look for deeper meaning in it, we are enjoying it for what it is. Because that is one of the things about art, be it highbrow, lowbrow, mainstream, or avant-garde: Some sort of thought went into its making — even if the thought was, “I’m going to do this as thoughtlessly as possible”! — and as a result, some sort of thought can be gotten from its reception….

So when you go out of your way to suggest that people should be thinking less — that not using one’s capacity for reason is an admirable position to take, and one that should be actively advocated — you are not saying anything particularly intelligent. And unless you live on a parallel version of Earth where too many people are thinking too deeply and critically about the world around them and what’s going on in their own heads, you’re not helping anything; on the contrary, you’re acting as an advocate for entropy.

And the greatest art work of the 20th century is…

… what? Not “Star Wars”? Not even “The Dark Knight”? (Wait — that’s the 21st.)

See? Cinephiles and music collectors aren’t the only ones who feel the compulsive need to make lists. Though, usually, we flaunt the subjectivity of the exercise (and try not to figure box-office popularity into the equation). But not this University of Chicago economist profiled in Monday’s New York Times:

Ask David Galenson to name the single greatest work of art from the 20th century, and he unhesitatingly answers “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” a 1907 painting by Picasso.

He can then tell you with certainty Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5 and so on, as well. […]

The filmmaker: Wayne Kramer on critics & criticism

Paul Walker is scared. And he’s running.

Wayne Kramer, the director of “The Cooler” and “Running Scared,” took the negative reviews of his last picture pretty hard. They weren’t all negative, though. Roger Ebert gave “Running Scared” three stars and wrote a dizzying description:

Speaking of movies that go over the top, “Running Scared” goes so far over the top, it circumnavigates the top and doubles back on itself; it’s the Mobius Strip of over-the-topness. I am in awe. It throws in everything but the kitchen sink. Then it throws in the kitchen sink, too, and the combo washer-dryer in the laundry room, while the hero and his wife are having sex on top of it.That kind of “pushing the envelope,” as he’s phrased it in interviews, appears to be pretty much what Kramer was going for.

But Kramer evidently felt there was some kind of critical curse on his film, which came out on DVD last week. In an interview with Scott Collura at Now Playing Magazine, Kramer says:

I feel it’s just one of those movies that people are gonna – That the marketing did not create an appealing image of what the film was, whether it be the trailers or posters, or whatever it was. People felt like this wasn’t something they needed to go see. Now, hopefully when they do see it, they’ll go, “Wow! We really misjudged this film,��? Or, “It’s a lot better than I was led to believe.��? We had some good reviews. I don’t mean to say every critic hated the film. We had like Roger Ebert, and Quentin Tarantino’s a big fan of the film and really comes out strongly for it; and Andrew Sarris and guys like Mick LaSalle. But if you check out a site like Rotten Tomatoes — I kind of have mixed feelings about that site because every Internet jerk with a website gets to play film critic. And usually it attracts the more elitist, snobbish sites that I just despise like Slant.com [actually, it’s slantmagazine.com]. Have you ever seen those guys? I mean they hate movies.

NP: Yeah.

WK: And you can print that, too. Please.

NP: I will!

Opening Shots update & lexicon

I still have plenty of excellent Opening Shots submissions to edit and post — and I’m doing my best to get frame grabs to accompany them whenever I can. (Quiz answers coming soon, too.) To no one’s surprise, “Star Wars” (1977) has been the most popular nomination — and for good reasons. But do keep ’em coming. I think of new brilliant opening shots every day, so if your initial ideas have already been mentioned, keep thinking. (Or, if you’d care to add to the discussion of a particular shot, Comments have supposedly been enabled on certain posts — though I have to approve ’em first.)

A few notes about terminology, just so we can be sure we’re all speaking the same language:

shot: a continuous image on film, from the time it begins (when the camera is rolling) until a cut (or fade out or dissolve) takes us to the next image. Sometimes the word “take” — as in continuous shot — is used interchangeably, although it is more specifically used to refer to one of several attempts to “get” a certain shot during filming. The editor often chooses between several takes of a given shot, and may cut them into shorter shots, or inter-cut different takes with other shots.)

pan: when the camera pivots horizontally, usually on a tripod. If a shot is strictly a pan, the camera does not move from its location, it just swivels — as if you were standing still and turning your head. It can, of course, be used in various combinations with any of the other techniques below. The opening shot of “Psycho” is a simple pan. Later, a zoom and a crane shot are used in the opening sequence.

tilt: like a pan, but a vertical movement rather than a horizontal one. The camera does not “pan” up the exterior of a skyscraper from a position on the sidewalk across the street; it “tilts” up. The last shot of Robert Altman’s “Nashville” is a simple tilt up to the empty sky.

dolly shot: a shot in which the camera actually moves — usually when mounted on a dolly or a crane, and often on tracks which have been put down to ensure a smooth-gliding and precise movement.

tracking shot: sometimes used interchangeably with “dolly shot,” but technically a shot where the camera moves with, or “tracks,” another moving object in the frame — whether from above, below, ahead, aside, or behind. (See opening shot of “Birth” — which also appears to use a crane and a Steadicam.)

crane shot: a movement where the camera is mounted on a crane (and sometimes a dolly as well), usually to rise above, or descend to, the scene of the primary action. Lots of movies end with crane shots that raise up on a crane and sometimes dolly back at the same time (think of “Chinatown” or “Silence of the Lambs”).

handheld shot: any shot in which the camera operator simply holds the camera manually, whether standing in one place or moving around within the scene. Often characterized by a certain shakiness that we’re used to experiencing as more immediate, immersive, or documentary-like than a solid, mounted camera, which can feel more detached and “objective.”

Steadicam shot: a Steadicam is a gyroscopic device that, as its name indicates, can be used to eliminate the shakiness of handheld shots for a smoother, more fluid movement — as if the camera is floating on air. (See “Halloween” for a dazzling example.) In a landmark shot at the beginning of Hal Ashby’s “Bound for Glory” (photographed by Haskell Wexler), the Steadicam operator is actually on a crane and lowered to the earth, where he steps off and continues the shot at ground level.

zoom: a zoom lens is simply a sliding telephoto lens that smoothly enlarges or reduces the size of objects in the frame optically, like looking through a adjustable telescope. The camera doesn’t necessarily move (though it sometimes does that at the same time), but appears to magnify or decrease whatever it’s looking at. As you zoom in on something, the image appears to “flatten.” (Recall the famous shot of Omar Sharif riding toward the camera across the desert in “Lawrence of Arabia” — he never really seems to get any closer because of the long telephoto lens that is used.) The dizzying “Vertigo” effect (after Hitchock’s innovation in that film) involves dollying in and zooming out at the same time (or vice-versa) — an effect employed memorably in a shot of Roy Scheider on the beach when a shark is sighted in “Jaws.”

TIFF 2007: The Evil That God Does

View image Song Kang-ho (“The Host”) and Cannes 2007 best actress Jeon Do-yeon in “Secret Sushine.” The use of pastel blues and pinks in this movie is… disturbing.

Lee Chang-dong’s “Miryang” (“Secret Sunshine”) begins with a CinemaScope view of a wide-open landscape beneath a big blue sky, and ends looking into the dirt of a tiny urban courtyard, in a corner with cement bricks, a discarded plastic bottle, a rubber hose, congealed muck and mud. How it makes that trajectory I am not going to say — although, if you were unfortunate enough to read the Toronto Film Festival catalog entry about the film (say, with an eye toward making a decision about whether to see it), you’ll find the film’s single most shocking plot development revealed at the beginning of the third paragraph.

This is criminally unfair to the audience, and another reason why, as I wrote recently, I like to know as little as possible about films before I see them, and engage in my due-diligence research afterwards. You don’t realize how much a film can be ruined even by seeing a few images in a trailer (or production stills) in advance. It’s terrible. Somewhere in your memory, you keep waiting for the images or moments to appear in the film, and too often the stuff the distributor has chosen for public release is designed to sell the picture but not to serve the audience’s appreciation or experience of it once they’ve bought a ticket.

“Secret Sunshine” is the meaning of the name of the South Korean town Miryang, to which Lee Shin-ae (Jeon Do-yeon, best actress at Cannes for this harrowing performance) and her son Jun are relocating in the first shot of the movie. That’s all the story detail you’re going to get from me. Like the first image (which suggests a road behind them that we only learn something about later), the final one indicates that the film is over, but that something continues. (It may also strike you as a miniaturized/essentialized recapitulation of a stunning shot of a lake from somewhere in the middle of the movie.)

The film is brave and unsparing (as is Jeon’s performance) and asks some challenging and disquieting questions, among them whether human values such as love, mercy, morality, meaning and forgiveness still have meaning if we shift the ultimate responsibility for them away from human beings onto some (Christian, in this case) concept of God. What is the significance of these principles if they’re viewed not in human terms but as supernatural absolutes? “Secret Sunshine” is film about hope and despair, about the stages of grief and several of the “Deadly Sins” (pride, most of all), and just how much a person can withstand (think Job) and still hang on to life, to meaning, to sanity.

It’s a hard film to write about without using superlatives.

Toronto Fest award winners

FIPRESCI Critics’ Choice: “D.O.A.P.”

“After 10 days, 352 films, and 27,747 minutes,” a Toronto International Film Festival press release announces, the “People’s Choice Award” (bestowed in recent years upon such films as “American Beauty” and “Tsotsi”), went to “Bella,” an American film directed by Alejandro Gomez Monteverde. The Prize of the International Critics (FIPRESCI Prize) was awarded to the British film “Death of a President,” directed by Gabriel Range “for the audacity with which it distorts reality to reveal a larger truth.”

More prize winners here. And I’ll be posting more of my own thoughts about this year’s frestival in the next few days.

Inglourious Basterds: Real or fictitious, it doesn’t matter…

Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds” is about World War II in roughly the same way that, I suppose, Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” is about a haunted hotel. The war is indeed the setting, but that’s not so much what the movie is about. I also don’t see it as an act of Holocaust denial or an anti-vengeance fable in which we are supposed to first applaud the Face of Jewish Revenge, and then feel uncomfortable sympathy for the Nazis. The movie comes down firmly on the side of the Jews, and of revenge, of an early end to the war and the saving of thousands of lives, with barely a quibble.

But while “Inglourious Basterds” is indisputably a WW II revenge fantasy (and, of course, a typically Tarantinian “love letter to cinema”), a theme that is central to nearly every moment, every image, every line of dialog, is that of performance — of existence as a form of acting, and human identity as both projection and perception. As you would expect from a film that is also an espionage picture and a detective movie, it’s shot through with identity games, interrogations, role-playing and people or situations that are not what they appear to be…

Wi-Fried in Urbana

The Illini Student Union wi-fi network has been down since late Friday/Saturday morning, so I’ll have to file more when I get back home (I’m between planes in Chicago now, on airport wi-fi). I think the Saturday convention of student scientists on the U of I campus (and/or the massive rain-storm the night before) may have overloaded the system.

Overheard in the hall outside one of the science convention meeting rooms, one student to another: “Well, should we just go back to our anti-social lives then?”

The Dilemma of two trailers: Judge for yourself

You’ve heard all the arguments. These two trailers represent two different approaches to selling the same movie. Which plays better for you, and why? Here’s the original:

The Dilemma Trailer – Watch more Movie Trailers

Here’s the substitute:

The only thing I’m going to say (that I haven’t already said here and here) is that neither of them makes me terribly excited to see the movie, which I feel like I’ve already seen several times before.

The world in a frame (or on a disc)

My recent post called “Framed” triggered memories of one the most evocatively titled books about cinema: Leo Braudy’s “The World in a Frame.” (What does it evoke? See quote from Martin Scorsese in upper right corner.) Published in 1976, the sub-title is “What We See in Films,” and re-reading the introduction and early chapters reminds me that we no longer see movies the way we did back then. Technology has fundamentally altered our perceptions of what a movie is. Here’s an observation (true at the time) from the intro, “Movies in Mind,” that I find rather moving:

Incidental talk after a screening, fan magazine biographies, and film criticism — all serve first of all to bring the short-lived image into a continuous world of ordinary discourse, to ensure its life beyond those moments in the dark, to make it exist. Unlike the products of the other arts [musical or theatrical recordings], movies are ephemeral. They aren’t available, at least not yet, for easy reference on bookshelves, in prints, or on records. One of the first problems for the student of film is taking notes in the dark — to catch for a moment the rapidly vanishing sound and image. So, too, the aesthetic situation of the movie audience in general is reminiscent of Homer’s first audiences. Once the bard has sung a line, the audience can’t demand to hear it again; and so the movie audience is passively drawn from scene to scene, with no ready text or score against which to judge their particular experience, with only the experience itself to generate its own standards, for when movies are repeated, unless you have a video-tape machine and can pirate fragments, they must be repeated in their entirety.

What Braudy describes there, of course, is the way all but those who worked in the movie business (from camera operators to editors to projectionists) had always experienced movies — as events that occurred at a particular time in a particular place. When we buy a ticket to a theatrical screening, we’re not purchasing anything concrete (besides the receipt that serves as proof-of-purchase for entry); we’re just renting space — a seat in an auditorium — for a particular length of time while images are projected on a screen, accompanied by synchronized sounds. There’s no guarantee that we will enjoy the images, or that we will find the experience worthwhile, only that we’ll be shown the movie whose title is printed on the ticket.

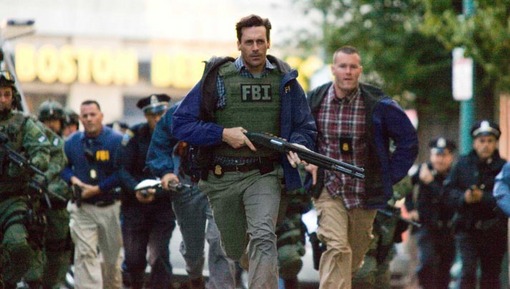

How to direct an action sequence, part 2

In his appreciative review of Ben Affleck’s “The Town” this week, Roger Ebert perfectly describes the feeling of disengagement I often notice in modern action sequences: “… I persist in finding chases and gun battles curiously boring. I realize the characters have stopped making the decisions, and the stunt and effects artists have taken over.”

That is precisely the way I feel about those sections of obligatory, unfocused movement in most movies. They’re almost like little intermissions shot by the B-team to give you a snack and potty break (“Let’s all go to th lobby…”). We know nothing consequence is going to happen. The movie has entered cruise control and for the next few minutes we’ll be watching one near-miss/narrow escape after another.

But this wasn’t (and isn’t) always so. David Bordwell looks to Hong Kong, and compares James Bond and Jackie Chan (by way of Sly Stallone), to show us how it’s done.

Obligatory Oscar analysis!

View image Pan looks into the future. What does he see?

I’m thrilled to report that Roger Ebert will be filing his own analysis of this morning’s Oscar nominations, too. In the meantime, here’s what I got:

Last summer, according to most industry prognosticators, this whole Oscar race thing was supposed to be all over already. Before its release, Clint Eastwood’s “Flags of Our Fathers” was widely expected to be greeted with flowers and statuettes. The combination of Eastwood and Paul Haggis (screenwriter of the last two Best Picture winners, Eastwood’s “Million Dollar Baby” and Haggis’s “Crash”) made the Red Carpet look like a cakewalk. “Letters From Iwo Jima” wasn’t even on the release schedule for 2006, so as not to interfere with “Flags”‘ Oscar chances. Martin Scorsese’s “The Departed” (2006) on the other hand, was cheered as a “return to his (generic) roots, ” a straight-up commercial cops-and-crooks movie to follow up his prestige-picture Oscar bids, “Gangs of New York” and “The Aviator,” but not something seriously For Your Consideration.

Meanwhile, the Christmas roadshow release “Dreamgirls” was positioned as the “Chicago” nominee, a glitzy musical that took years to get to the big screen (the stage version played on Broadway more than 20 years ago), and was thought to be a shoo-in for a Best Picture nomination.

Don’t you love it when the conventional wisdom is just wrong?

Story continued at RogerEbert.com

Intelligent Design: Tried and convicted

… of impersonating a scientific theory. The 2005 federal court case was recounted in a 2007 NOVA documentary called “Judgment Day: Intelligent Design on Trial” that re-aired on PBS this week (and can be viewed online here; full transcript here.) I recommend it as a detoxifying antidote to Ben Stein’s risible 2008 “Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed.” Among my problems with that bait-and-switch doc was that it offered no evidence to suggest that ID should be considered a scientific theory any more than, say, creationism or astrology. Of course, there are good reasons for that — the main one being that it was invented as a hasty response to the 1987 Supreme Court decision that found the teaching of creationism as science in public schools was a violation of the Establishment Clause of the US. Constitution.

“Darwin’s Black Box” author Dr. Michael Behe, a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, which promotes ID, testified under oath that his definition of alternative “scientific theory” would include astrology as well as Intelligent Design (but not creationism). It seems the irreducibly supernatural ID was born under a bad sign.

A few other highlights:

Speaking of framing…

I’m in the process of tracking down, rescuing and reposting all my video essays that disappeared along with iKlipz when the latter died unexpectedly earlier this year. This one, about M. Night Shyamalan’s “Unbreakable,” came to mind when posting Richard T. Jameson’s comments on framing and John Carpenter’s “Halloween.”

TIFF 2007: The rituals of romance

View image People. They can be quite beautiful.

“Love comes in at the eye.”

— William Butler Yeats — and David Cronenberg (“Videodrome”)

Eric Rohmer has made a career out of chronicling the rituals of romance (and Romanticism), from the 6th century to the present, and from his celebrated film series, Six Moral Tales (1963 – 1972), Comedies and Proverbs (1981 – 1986), and Tales of the Four Seasons (1990 – 1998). And then there are those elegantly contrived period pictures that don’t fit into the series, like “Perceval,” “The Marquise of O,” “The Lady and the Duke” (which I haven’t seen) and now “Les Amours d’Astrée et de Céladon” (known in English-speaking Canada as “The Romance of Astrea and Celadon”).

Two of my favorite Rohmer films (perhaps my two very favorites) seem to be among his least-mentioned: “Perceval” and “Summer” (aka “Le Rayon vert”) — the former completely artificial (shot on a painted soundstage) and the latter an equally charming portrait of a romantic klutz.

“Les Amours d’Astrée et de Céladon” is a Rohmerian delight, another ritualized romance (highly mannered behavior, poetic language) played out in a naturalistic pastoral setting (an unblemished slice of French countryside around the River Lignon). It’s all an elaborate game of appearances, deceptions, seductions and betrayals — about what is seen or not seen, what is said or not said, and how love comes in at the eye, but is sealed with the mouth. The characters — high-born and common-folk; shepherds, shepherdesses, nymphs and druids — intermingle in a realm of symbols and prophecies that is both fleshly and spiritual, earthy and philosophical. It’s a moral tale, a comedy, a proverb, and a seasonal story (midsummer, I’d say) that toys enchantingly with the paradoxical nature of love, and the contradictory distinctions between the lover and the beloved.

I don’t even want to try to describe the fantastical plot, but let it suffice to say that young lovers are separated by a misunderstanding, and they must cross the river that flows between them, and flirt with crossing sexual boundaries, in order to reunite as one. The teasing, seductive visual and narrative strategy (adapted from the 17th century novel “L’Astrée” by Honoré d’Urfé), is designed to teasingly delay gratification until it climaxes in a bedroom with three voluptuous women in loose white nightdresses sleeping in one fluffy feather-bed (two shepherdesses and one nymph), and a shepherd disguised as a druidess (but really the long-lost lover of one of the shepherdesses) across the room, alone, in another bed. The sexual tension is ripe and delicious… and as unbearably tantalizing for the audience as it is for the frustrated lover.

Rohmer loves to photograph the most beautiful creatures in the most luminous light, and at age 87 his eye and his sense of rhythm is faultless. Astrée (Stéphanie de Crayencour) is a fair and incandescent beauty, and the strikingly androgynous Céladon (model Andy Gillet) makes as lovely a druidess as he does a shepherd. Not really my type, but I wouldn’t kick this Frog out of a Mistletoe Festival…

(Thanks to Kathleen Murphy for her unprintable shorthand description of erotic storytelling in and about the courts of Henry IV and VIII, which made me appreciate this movie all the more.)

Letting Go of God

View image: Julia’s new CD: A beautiful loss-of-faith story.

A personal note: I hope you’ve seen my dearest friend Julia Sweeney’s “God Said ‘Ha!'” (Roger Ebert’s review here), which is available on DVD. And I hope you’ve seen her stage monologues, “In the Family Way,” about her decision to adopt her daughter, Tara Mulan Sweeney, from China (my photo account of the journey itself is here, with my text written in Borat-esque Engrish); and, especially, “Letting Go of God,” about her messy breakup with the Almighty, which she has performed in LA and New York (she’s about to do nine shows through October 29 at the Ars Nova Theatre — right next to “The Colbert Report”!) — and abridged one-night engagements in a few other cities, including Seattle and Austin, where she did Q&As afterwards with Ira Glass.

You may have heard a small excerpt from “Letting Go of God” on Glass’s “This American Life” NPR show, the most popular episode in that broadcast’s history. But now — for the first time! — you can obtain a double-CD of the whole show (which comes with a beautiful booklet transcription of the piece) — as well as a separate, single-CD recording of “In the Family Way.” I’m so proud of, and moved by, Julia’s accomplishments that I could do a dance — which I indeed do, but in private.

Some of the happiest moments of my life have been working and playing and collaborating and consulting with Julia in various respects over the last 30 years of our enduring friendship — on various projects for stage, print, TV and movies — and I’m delighted to be listed as an Extra Special Creative Consultant on “Letting Go of God.” The CDs go on sale at her web site October 25 (my birthday). “Letting Go of God,” like “God Said ‘Ha!’,” will become a film of some kind (Julia is still playing around with ideas for how to shoot it). Here’s an excerpt — two of my favorite passages (although others are considerably funnier) — that just happen to address this blog’s core subject. No, not movies — critical thinking:

God requires faith. Faith does not require evidence, right? But the more I thought about it, my faith was based on evidence. The evidence of how I felt when I prayed. The evidence of everyone believing in God, almost everyone I had ever met from the time I was a kid. The evidence of what I had been taught by other people I trusted, admired, and who ultimately had authority over me.

So, my faith in God was based on evidence. Well then, how could I not examine that evidence? But how did I examine anything? How did I know what I knew? I had to know! […]

I thought of Pascal’s Wager. Pascal argued that it’s better to bet there is a God, because if you’re wrong there’s nothing to lose, but if there is, you win an eternity in heaven. But I can’t force myself to believe, just in case it turns out to be true. The God I’ve been praying to knows what I think — he doesn’t just make sure I show up in church. How could I possibly pretend to believe? I might convince other people, but surely not God.

And plus, if I lead my life according to my own deeply held moral principles, what difference did it make if I believed in God? Why would God care if I “believed” in him?

It’s a funny, informative, enlightening and suspenseful struggle if, like Julia (and me), you’re inclined to Question Authority and figure things out for yourself. (Which is not to say you’ll necessarily share Julia’s conclusions — and she doesn’t expect you to — just that you’ll appreciate the switches, setbacks, false peaks and hard-won lessons of the journey…)

Barry Levinson on how to handle criticism

In a reply to what he feels is a misleading (nay, delusional) review of his essay film “Poliwood” by New York Times TV critic Alessandra Stanley, Barry Levinson offers this sound advice:

To reiterate, criticism is a part of a filmmaker’s journey. Any time you attempt to tackle a subject that is complicated, one is open to criticism. It comes with the territory. A WARNING: to any thin-skinned filmmaker, get out of this line of work quickly or you’ll die a hemophiliac. But when one’s work is used as fodder for a critic such as Ms. Stanley, then I feel I must speak up… and throw caution to the wind. […]

The New York Times is known throughout the world as one of the leading newspapers in this country. It has excellent film criticism and book reviews. And a very strong op-ed page. Where Ms. Stanley fits into this strong lineup is questionable at best.

As a filmmaker, all you can expect is for your work to be examined for what it is….

The arrival of The Prisoner, then and now: “We Want Information!”

AMC’s re-do of the classic British TV series “The Prisoner” gets under way Sunday night, following the conclusion of “Mad Men”‘s third season last week. The new version stars Jim Caviezel as Number Six and Ian McKellen as Number Two. (The great Leo McKern played Number Two a couple times in the original series, and there were some other repeats as I recall, but generally there was a new Number Two each week.)

From the teasers it appears that the new version (tagline: “You Only Think You’re Free”) takes place in a desert suburb of Dubai rather than a quaint seaside village. (Actually, the new “Prisoner” was shot in Cape Town, South Africa, and Swakopmund, Namibia.) The big white bouncy billowy security devices are back. But I’m most interested in the opening credits sequence, because I became so enamored with the ritualistic nature of the earlier one, as you can see from the following obsessive video analysis originally published in 2008:

(Rescued and reposted months after the death of iKlipz caused all my video essays to disappear from the web. Originally published — with more on “The Prisoner” here.)