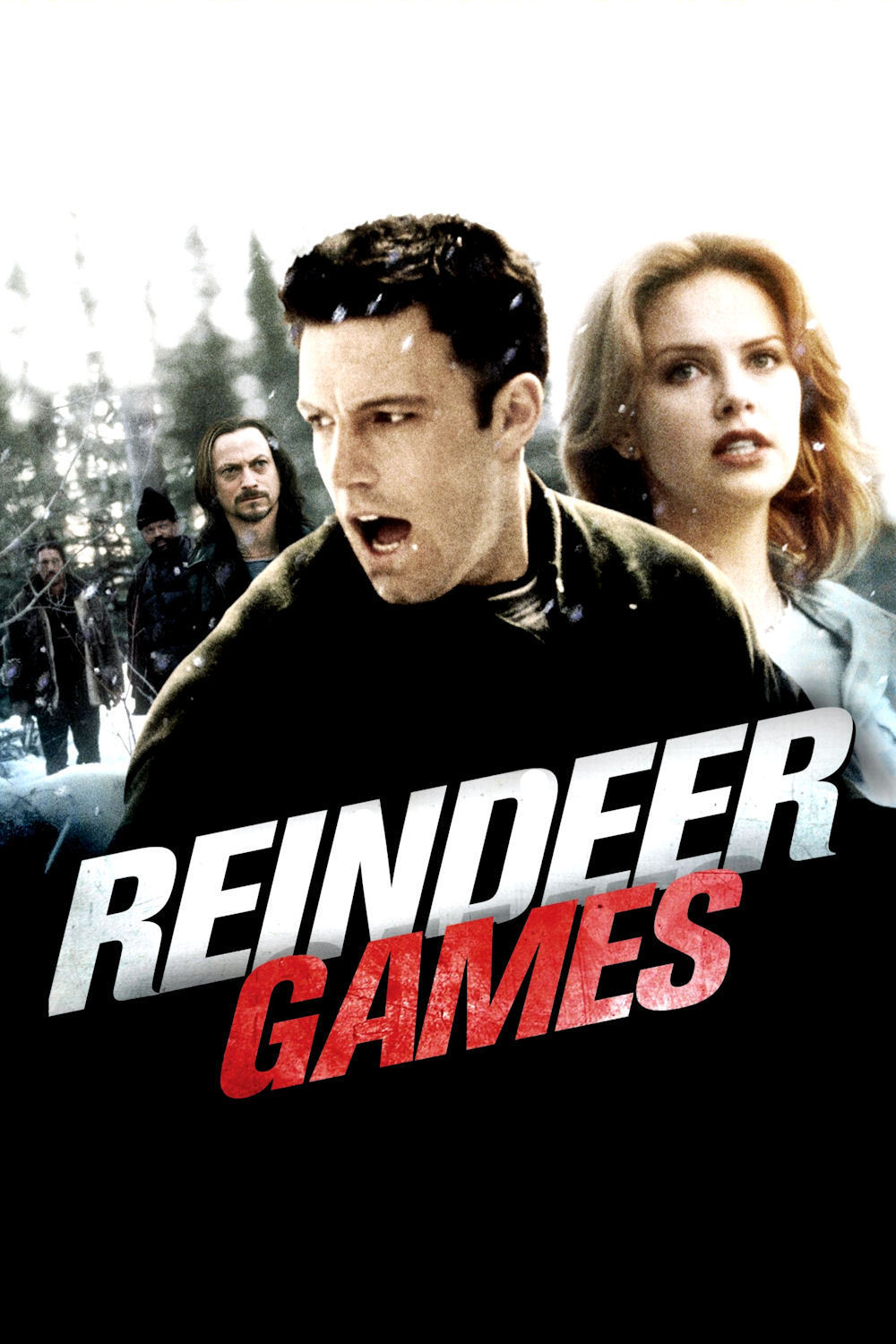

John Frankenheimer Movie Reviews

Blog Posts That Mention John Frankenheimer

Another Chance: On the Sustained Power of John Frankenheimer’s Seconds

Wael Khairy

John Frankenheimer: A master craftsman

Roger Ebert

Interview with John Frankenheimer

Roger Ebert

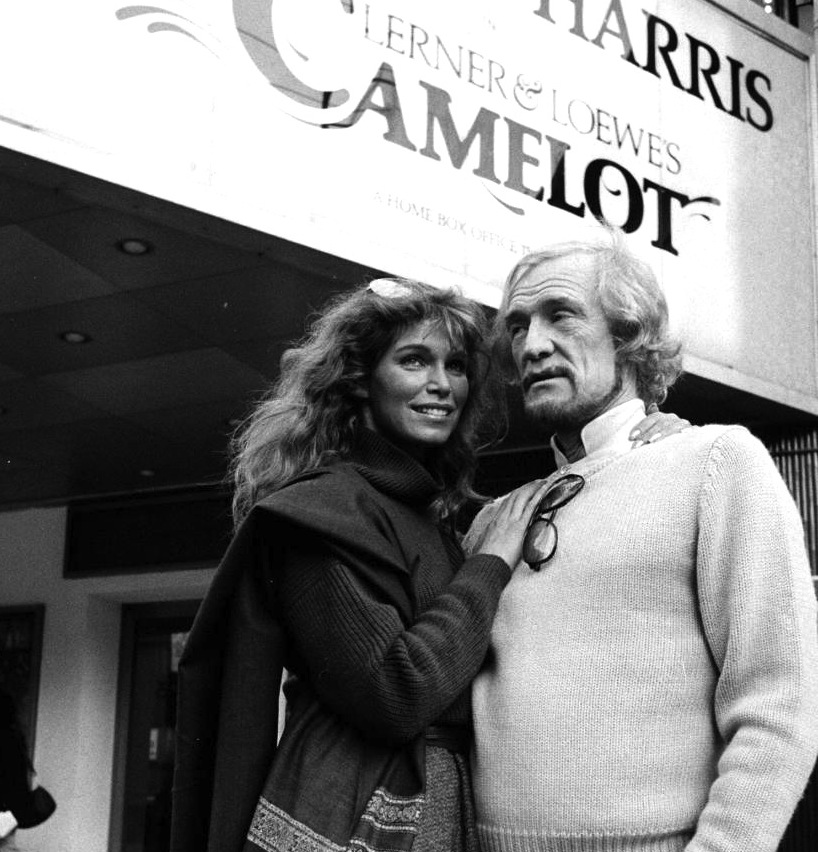

Richard Harris: Don’t let it be forgot

Roger Ebert

KVIFF 2025: Stellan Skarsgård on “Sentimental Value,” Ingmar Bergman, and Cinematic Empathy

Isaac Feldberg

Lookin’s Free: Joe Don Baker (1936-2025)

Scout Tafoya

The Most Unsung Leading Man of His Generation: Val Kilmer (1959-2025)

Scout Tafoya

I Think Of Them As The Work: Gene Hackman (1930-2025)

Scout Tafoya

How Cold War Thrillers Expressed Presidential Campaign Concerns

Bijan Bayne

An Unforgettable Performer: Piper Laurie (1932-2023)

Dan Callahan

He Did It All: William Friedkin (1935-2023)

Scout Tafoya

The Ranown Westerns Join the Criterion Collection

Walter Chaw

Don’t Forget Your Place: On Joseph Losey’s The Servant

Walter Chaw

A Disappearing Act: David Warner (1941-2022)

Simon Abrams

Uncanny Talent: Clarence Williams III, 1939-2021

Matt Zoller Seitz

Jessica Walter: 1941-2021

Roxana Hadadi

The Joke’s On Him: Tom Cruise and Eyes Wide Shut

Matt Zoller Seitz

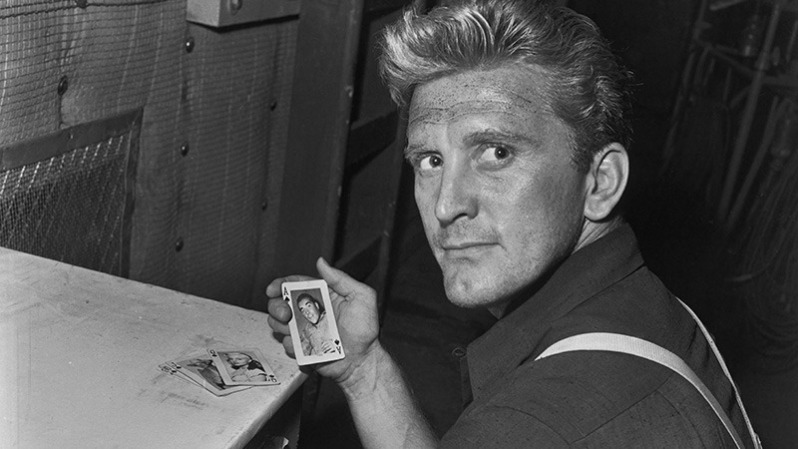

Kirk Douglas: 1916-2020

Peter Sobczynski

Beata Virgo Viscera: a Feature-Length Unloved Video Essay by Scout Tafoya

Scout Tafoya

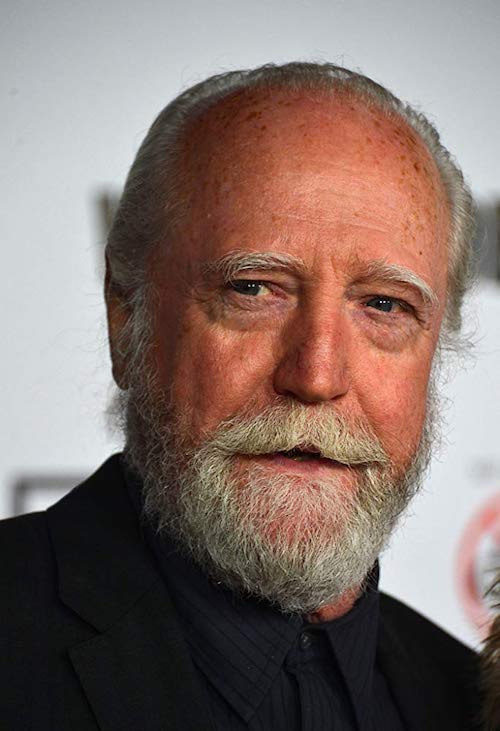

Scott Wilson: 1942-2018

Peter Sobczynski

A musical soul: Jonathan Demme, 1944-2017

Matt Zoller Seitz

The Unloved, Part 30: Torn Curtain & Topaz

Scout Tafoya

Moving Pictures: A Recap of the 2016 TCM Classic Film Festival

Laura Emerick

An Overview of the 18th Annual Ebertfest

Peter Sobczynski

Home Entertainment Consumer Guide: March 17, 2016

Brian Tallerico

Thumbnails 5/7/15

Matt Fagerholm

Beyond Narrative: The Future of the Feature Film

Roger Ebert

Reverse Trip: Charting the History of Bong Joon-Ho’s “Snowpiercer”

Scout Tafoya

Thumbnails 10/4/2013

The Editors

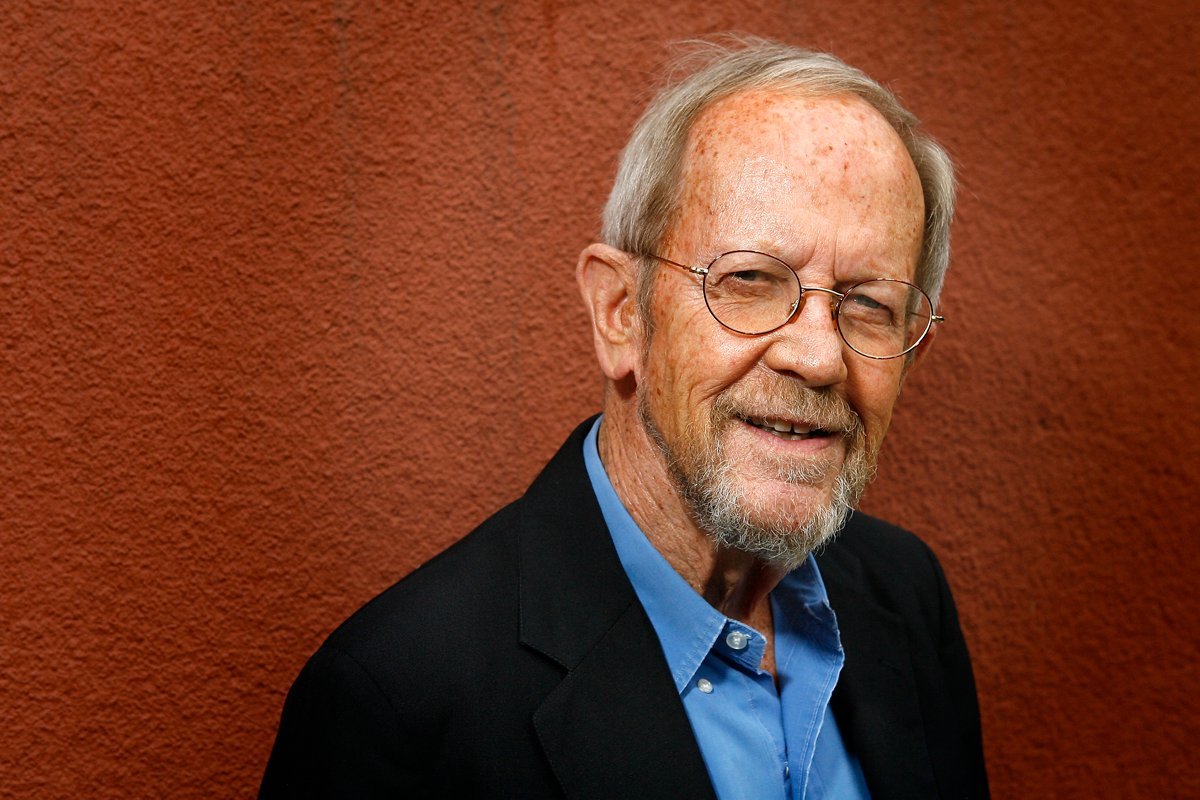

Elmore Leonard, 1925-2013: An Appreciation

Odie Henderson

Why most modern action films are terrible

Nick Schager

“Die Hard” in a building: an action classic turns 25

Matt Zoller Seitz

Looking back at 1968, through a lens

Roger Ebert

What is the Cold War good for? A director’s career

Roger Ebert

The Best 10 Movies of 1988

Roger Ebert

101 102 Movies You Must See Before…

Jim Emerson

The great movies (almost) nobody voted for

Jim Emerson

Name That Director!

Jim Emerson

You better you better you best: The better of the best lists

Jim Emerson

Agents of chaos

Jim Emerson

Raccoon Nation: The hep cats of the ‘hood

Odie Henderson

Telluride #3: Mickey in the limelight

Roger Ebert

Cable goes where studios fear to tread

Roger Ebert

Sidney Lumet: In Memory

Roger Ebert

Janet Leigh dies at age 77

Roger Ebert

Frank Sinatra’s legend lives on in films

Roger Ebert

Robert Evans: Life is suite

Roger Ebert

Richard Harris: Don’t let it be forgot

Roger Ebert

James Wong Howe, Master of Lights

Roger Ebert

By the time we get to Phoenix, he’ll be laughing

Roger Ebert

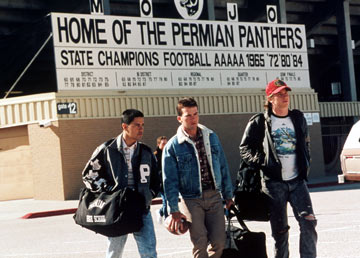

We’re not in Texas anymore… are we?

Roger Ebert

Popular Reviews

The best movie reviews, in your inbox