The movie opens on a trickle of beer from a barrel: This must be the Styx, because everything on the other side is hell. The camera tracks to the back room of an Irish saloon in Greenwich Village, summer, 1912, where the regulars are tossed about like sleeping rag dolls. Snores, snorts and cries of terror from fearful dreams. In the corner, one man remains awake, his cynicism too deep to allow easy dreams.

The man’s name is Larry, and he used to be a Wobbly before he abandoned the movement for his own personal scorn of faith. The bartender wearily joins him at the table and they wait for the day. There are so many men in the room that is seems impossible we will eventually get to know them all, but we will, and also the three whores upstairs, and especially the man they are all waiting for, the iceman, Hickey.

The owner of the bar is named, ironically, Harry Hope. He has so long ago abandoned any hope that he has not even stepped outside his establishment in 20 years. This place is the end of the road, the bottom of the sea, Larry says. But every man except Larry has a “pipe dream” – something to keep him going. Tomorrow one of them will sober up and get his job back. Tomorrow the assistant bartender will marry one of the whores and make her respectable. Tomorrow. Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh” is the work of a man who has very nearly abandoned all hope. The only characters in it who summon up the courage to act (not to act positively, but to act at all) are Hickey, who kills his wife, and the boy Don, who kills himself. Larry, who is always the most intelligent man in the room, comes to the conclusion at the end of the play that death is not to be avoided but even to be welcomed.

And yet the play sings with a defiant urge to live. The derelicts who inhabit the two rooms of this seedy saloon depend upon each other with a ferociousness born of deep knowledge of each other. The two old soldiers, for example, one British and the other Boer in the South African War, have almost gotten to love each other, so deeply do they depend on their ancient hate.

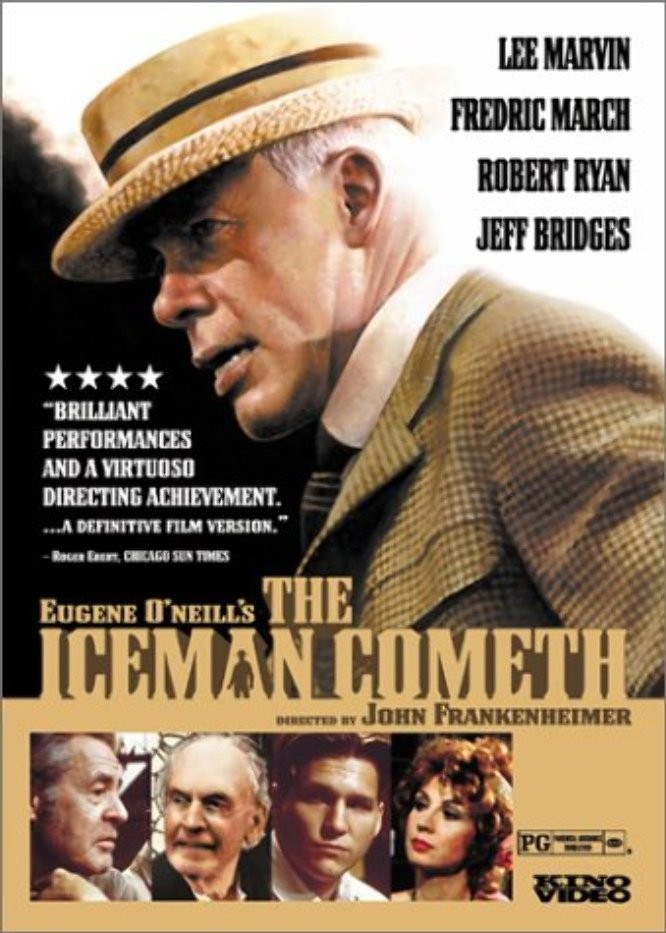

O’Neill’s play was not only so despairing but also so long (four hours and one minute in the film version) that it was not produced on the stage until 1946, seven years after he finished it. It’s staged infrequently, despite its stature as the most ambitious play of America’s ‘greatest playwright. The American Film Theater production of it, directed by John Frankenheimer, is thus all the more welcome. The play was clearly too difficult to be done as an ordinary commercial movie, but now it has been preserved, with a series of brilliant performances and a virtuoso directing achievement, in what has to be a definitive film version.

There isn’t a bad performance in the film, but there are three of such greatness they mesmerize us. The best is by the late Robert Ryan, as Larry, and this is possibly the finest performance of his career. There is such wisdom and sadness in his eyes, and such pain in his rejection of the boy Don (who may possibly be his own son), that he makes the role almost tender despite the language O’Neill gives him. It would be a tribute to a distinguished career if Ryan were nominated posthumously for an Academy Award.

Lee Marvin, as Hickey, has a more virtuoso role: He plays a salesman who has been coming to Harry’s saloon for many years to have a “periodical drunk.” This time he’s on the wagon, he says, because he’s found peace. We discover his horrible peace when he confesses to the murder. Marvin has recently been playing in violent action movies that require mostly that he look mean; here he is a tortured madman hidden beneath a true believer.

I also liked old Fredric March, as Harry Hope. He’s a pathetic pixie who tolerates his customers for the security they give him. To be the proprietor of a place like this is, at least, better than being a customer. But not much better. And so for four hours we live in these two rooms and discover the secrets of these people, and at the end we have gone deeper, seen more, and will remember more, than with most of the other movies of our life.