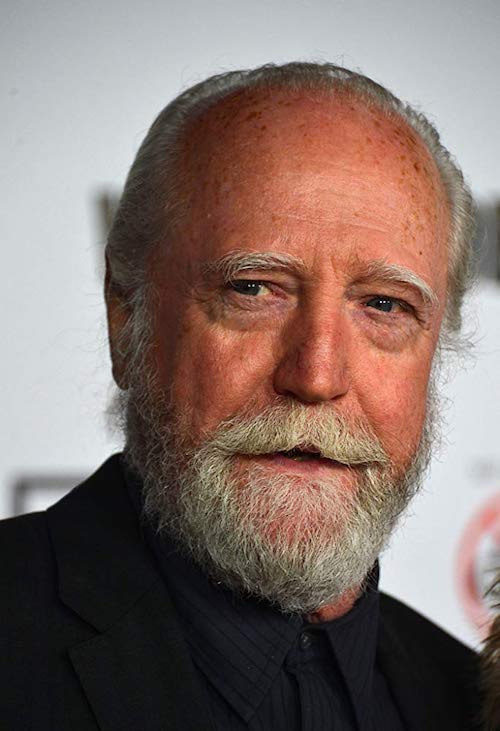

It is hard enough writing a tribute that celebrates the life and work of someone you know only from their work. It becomes exponentially more difficult when writing about someone you have actually met, and therefore know them as more than just a collection of film titles that you have seen and admired over the years. That is the situation that I find myself in writing about actor Scott Wilson, who passed away yesterday at the age of 76 from complications from leukemia. Over the years, I have admired many of his performances. But I was also lucky enough to meet him in person several times, even getting the honor of sitting next to him on a panel at Ebertfest, where he was a regular and much beloved guest. Every time I got to talk to him, he was unfailingly kind and open and, best of all, filled with great stories. I mention all of this here upfront because as you read this, I want to stress the fact that he was not just a great actor but a great guy as well.

Born in Thomasville, Georgia on March 29, 1942, Wilson had originally planned to attend Georgia’s Southern Tech University on a basketball scholarship to study architecture. Instead, in a move that one could see a character of his making in a movie, he elected to hitchhike out to Los Angeles. Once there, he happened to meet an actor in a bar one day who invited him to come along with him to an audition. Wilson didn’t land the part but clearly found his vocation and for the next several years, he supported himself with menial jobs while appearing in local theatrical productions. Unlike a lot of actors, who find themselves slogging through a number of fairly embarrassing movie roles before hitting the big time, Wilson was lucky enough to start his film career as close to the top as possible when Norman Jewison hired him to portray one of the murder suspects in the controversial, award-winning drama “In the Heat of the Night” (1967, pictured above). That same year, director Richard Brooks hired him for his next project, an adaptation of Truman Capote’s landmark work “In Cold Blood” in which he would co-star with Robert Blake as Richard Hickock, one of two men who break into the isolated house of a farm family and kill the four people inside in a robbery gone bad, a crime for which they are eventually captured, tried, and executed.

In making the film, Brooks strove to bring as much authenticity to the project as possible, even going so far as to shoot scenes inside the actual house where the crimes happened and the courtroom where the trial was held. It is entirely possible that he initially cast Wilson for the same reason as he happened to have a striking physical similarity to the person that he was playing. If that was the case, Brooks certainly got a bonus because Wilson’s performance as Hickock is absolutely chilling and wrenching to watch—while co-star Blake is just recognizable enough to remind you that he is acting (not to demean his strong performance at all), Wilson all but disappears into the part to the point where you actually feel at times as if you are watching the real Hickock going through these events. He was so effective in the role, in fact, that an argument could be made that it was actually detrimental to his career as a whole—despite receiving numerous accolades and the cover of Life, he never quite attained the level of stardom one might have naturally expected after appearing in a film where he made such an impact.

Although he would not make a lot of movies in the wake of “In Cold Blood,” he nevertheless found himself appearing in a number of intriguing projects. He turned up in such projects as Sydney Pollack’s surrealistic war drama “Castle Keep” (1969), John Frankenheimer’s period drama “The Gypsy Moths” (1969), Robert Aldrich’s gangster thriller “The Grissom Gang” (1971), the cop drama “The New Centurions” (1972, the weirdo hillbilly revenge saga “Lolly-Madonna XXX” (1973) and the small but undeniably important role of George Wilson in the heavily hyped Robert Redford-Mia Farrow version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” (1974).

His best performance during this period was in perhaps the least seen of the films he made during that time, the genuinely bizarre “The Ninth Configuration” (1980, pictured above), in which writer/director William Pete Blatty adapted his own novel about an isolated castle serving as an asylum for mentally ill US soldiers whose new commanding officer, Colonel Kane (Stacey Keach) allows the patients to embrace their delusions in an attempt to rehabilitate them—the joke is that the guy in charge may actually be just as crazy as the people he is overseeing. Wilson plays Billy Cutshaw, an astronaut who has been sent to the facility after suffering a nervous breakdown that led him to abort a moon launch. The scenes between Cutshaw and Kane in which they debate the existence of God and the afterlife turn out to be the emotional and dramatic anchor of a film that could have spun off into pure weirdness (and believe me, it gets pretty weird) without them and show both actors at their very best. Although it would go on to become a cult favorite, the film bombed when it came out but Wilson’s performance made enough of an impact that he received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Supporting Actor.

The next couple of decades saw him continuing to work in an eclectic variety of films, which kicked off with an appearance in a genuine American classic, Phillip Kaufman’s “The Right Stuff” (1983), in which he played test pilot Scott Crossfield. From there, he turned up in such films as “Blue City” (1986), “Malone” (1987) and Walter Hill’s twisted crime drama “Johnny Handsome” (1989) and then reunited with Blatty on the equally bizarre and underrated “The Exorcist III” (1990), a genuinely creepy and very strange continuation of Blatty’s legendary creation. There were also some instantly forgettable films like “Young Guns II” (1990) and “Pure Luck” and more ambitious projects like the moody drama “Flesh & Bone” (1993) and “Geronimo: An American Legend” (1993). But he found himself in another adaptation of a Truman Capote work, the nostalgic comedy-drama “The Grass Harp” (1995) and stood out as the chaplain in the powerful drama “Dead Man Walking” (1995).

His most significant role during this time would once again come from an unexpected source, an adaptation of the children’s book “Shiloh” (1996), in which he plays Judd Travers, the cruel and abusive owner of the titular beagle who winds up befriending a neighbor boy whose own family has also been terrorized by Judd over the years. Yes, the description may make it sound dull at best and icky at worst but it proved to be a surprisingly effective drama for younger and older audiences alike. Wilson’s performance was a key factor in that—instead of playing the character as some kind of cartoonish monster, he quietly shows us the lifetime of hurt that has caused him to try and inspire as much hurt to others as possible. The effectiveness of his work was best illustrated after a screening of the film at Ebertfest where he was joined on stage by a group of kids with questions for him, the first one being “Mister, why are you so mean?” His perfect response was “Honey, I just don’t know but I learned my lesson.” Indeed, over the course of two sequels, “Shiloh 2: Shiloh Season” (1999) and “Saving Shiloh” (2006), his character would slowly begin to grow past the hatred in his life to the point where it became obvious that the series was really about him all along.

At last, Wilson began working steadily in film projects both big and small. He appeared in historical epics like “Pearl Harbor” (2001) and “The Last Samurai” (2003) and small indie films like Victor Nunez’s “Coastlines” (2002), the celebrated “Junebug” (2005, with the Ebertfest appearance pictured above) and Joey Lauren Adam’s lovely 2006 directorial debut “Come Early Morning.” He had a brief but powerful bit as the final victim of serial killer Aileen Wurnos (Charlize Theron) in “Monster” (2003) and unexpectedly popped up amid the chaos in Bong Joon-Ho’s wild monster movie extravaganza “The Host” (2006). On television, he had a recurring role on “CSI” and appeared on such shows as “The X-Files” and “Law & Order.”

His best performance of this period—possibly my favorite performance of his entire career, to be honest—was in “Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon” (2006), a hilarious mockumentary-style spoof of slasher movies in which a documentary crew follows a would-be psycho killer as he meticulously prepares to slaughter the usual crop of dumb teenagers over the course of one night. The film effectively goofs on all the cliches and tropes of the genre, but hits its high point when Wilson turns up as Leslie’s mentor in murder, a former killer himself (it is implied that he is the one behind the killings in the classic “Black Christmas”) who offers sage advice on how one can survive such an attack (“Run like a motherfucker and don’t stop till the sun comes up”) in such a deadpan manner that practically every line he utters turns out to be gold. When I was on that panel with him, I even made sure to take a moment to praise both that film and him to the skies, and while I suppose that diversion may have perplexed many in the audiences who had not seen it (although a cult favorite now, it received a pathetically tiny theatrical release), I am now happier than ever that I did.

Although Wilson would continue to turn up in films from time to time—he made an especially impressive appearance in “Hostiles” (2017), which would prove to be his final film—the later years of his career would find him working more in television. There, he would become best known for playing Hershel Greene for several seasons of the long-running hit “The Walking Dead” and turned up in episodes of such shows as “Justified,” “Enlightened,” “Damien,” “Bosch” and “The OA.” Because of his association with “The Walking Dead,” it was ensured that his passing would not go unnoticed and I can only hope that the renewed interest in the man will inspire some to go looking at some of his past work to see what a truly gifted and memorable actors he was. He may not have been the most famous of actors but when it comes to the things more important than fame—little things like talent and decency—what he left behind will more than stand the test of time.