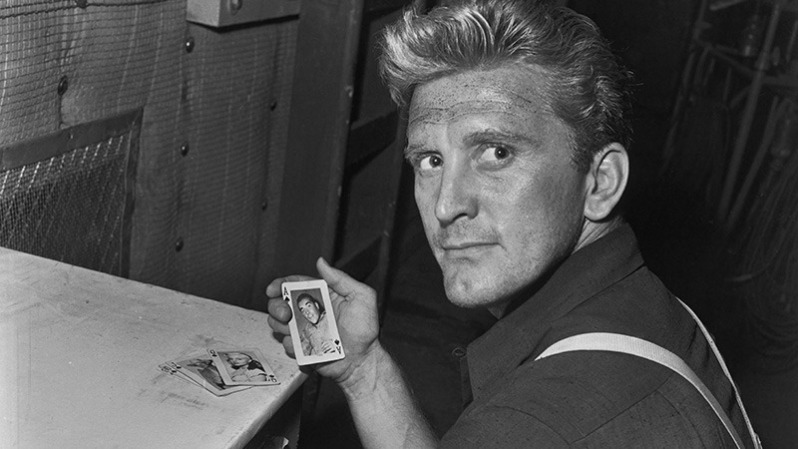

As a result of having caught the movie bug at a very early age, I must confess that in many cases, I cannot specifically remember when I first encountered many of the greats of the silver screen for the first time—I have adored the Marx Brothers for as long as I can recall but I could not tell you the exact circumstances of that initial encounter. In the case of Kirk Douglas, however, I actually do recall what I believe was the first time I saw him, certainly the first time on the big screen. For reasons that remain lost in the mists of time, my parents took me and my younger brother out one evening in the summer of 1979 to go see “The Villain,” a slapstick Western comedy clearly intended to suggest a live-action version of the old Road Runner cartoons that was directed by Hal Needham and featured Douglas alongside Ann-Margaret, Paul Lynde, Strother Martin and a muscleman with the unlikely name of Arnold Schwarzenegger.

At this point, many of you might reasonably ask why I would kick off a tribute to one of Hollywood’s most celebrated screen icons on the occasion of his passing yesterday, at the age of 103, by bringing up what could charitably be described as one of the lower points of a filmography stretching over seven decades. Here’s the thing—even at the tender age of seven or so, I kind of recognized just how stupid this movie was. At the same time, I still got a few chuckles out of it and they were almost entirely due to Douglas’s turn as the hapless bad guy. As bad as it was, he threw himself into the part with such incredible energy and determination that he took a nothing part and made it occasionally work. Even as a kid, I was able to recognize this on some fundamental level and appreciate his efforts. This also set me up for a pleasant discovery a couple of years later when I began seeing some of his other films and watched as he applied those same talents to slightly more elevated material and created one of the most indelible bodies of work by any actor to ever grace the big screen.

He was born Issur Danielovitch Demsky in Amsterdam, New York on December 9, 1916, one of the seven children born to Jewish immigrant parents from the Russian Empire. He grew up poor and discovered an interest in acting in high school that he continued while studying at St. Lawrence University, where he graduated in 1939. From there, he went to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and then went on to join the Navy in 1941 following the United States entering World War II. Returning to New York after being discharged in 1944, he worked on the stage and on the radio until another former classmate from the American Academy, Lauren Bacall, recommended him to producer Hal B. Wallis, who was looking for a new face to appear opposite Barbara Stanwyck in his upcoming dark drama, “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers” (1946)

Although this was only Douglas’s first film, people took notice of his appearance and he was soon working steadily as a supporting actor in films like the noir classics “Out of the Past” (1947) and “I Walk Alone” (1948)—the latter would find him appearing opposite Burt Lancaster for the first of seven films, and the soapy melodrama “A Letter to Three Wives” (1949) and making his Broadway debut in a 1949 production of “Three Sisters.” 1949 was also the year that he first achieved leading man status with “Champion,” in which he played a ruthless boxer who will go to any lengths to make it to the top. Doing the film was a bit of a risk—few actors at the time wanted to play a character as resoundingly unlikable as Michael “Midge” Kelly and to take the part meant turning down a role in an MGM production that would have paid three times what producer Stanley Kramer was asking—but it wound up paying off with rave reviews and an Oscar nomination for Best Actor. Building upon the success of “Champion,” Douglas began to seek out parts that allowed him to demonstrate his intensity as an actor and his willingness to play less-than-heroic parts. In 1950, he portrayed a musician inspired by Bix Beiderbecke in “Young Man with a Horn” and appeared in a screen adaptation of “The Glass Menagerie.”

1951, however, would prove to be the year where he solidified his stardom for good. In “Along the Great Divide,” he portrayed a federal marshal trying to bring back a suspected cattle rustler and murderer to trial in the face of a lynch mob. Although the least of the films he made during this year, it was his first Western, a genre that he would return to time and again over the years. He then delivered one of his greatest performances as an unscrupulous news reporter who goes to outrageous lengths to create and extend a story that he sees as his ticket back to the big time, no matter who else suffers as a result, in Billy Wilder’s still-corrosive and biting drama “Ace in the Hole.” Although a notorious critical and commercial flop when it was first released, the film has gone on to be regarded as one of the great Hollywood films of the era and a good deal of that reappraisal is due to the almost terrifying amount of craven energy that Douglas brought to the role of Charles Tatum—he never once tries to make viewers find any sympathy for him and makes the character all the more fascinating as a result. Although now considered a master class in acting, Douglas did not even earn an Oscar nomination for this film. He completed the year with “Detective Story,” an intense noir from William Wyler in which he played a New York cop whose relentless pursuit of the city’s criminal element winds up coming back to haunt him in unexpected ways.

Over the next few years, Douglas would continue to be ranked among the most popular movie stars of his time. He received his second Oscar nomination for his performance as a manipulative film producer who exploits everyone around him in his quest to succeed in “The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952). He portrayed Odysseus in a screen version of “Ulysses” (1954) and showed a lighter side in the enormously successful underwater fantasy epic “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” His third and final Oscar nomination came in 1956 for his portrayal of Vincent van Gogh in “Lust for Life” and played another famous name from the past a year later when he appeared as Doc Holliday in the Western favorite “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” (1957). Inspired by the example set by Lancaster, Douglas decided to form his own production company, Bryna Productions, in 1955 and signed a distribution deal with United Artists.

One of those films that emerged from that deal came about when the filmmaking team of director Stanley Kubrick and producer James B. Harris, who had a critical success with their crime drama “The Killing” (1956), contacted Douglas with a screenplay that Kubrick and Calder Winningham had adapted from a 1935 novel by Humphrey Cobb based on a true incident during World War I in which four French soldiers were executed on trumped-up charges that were essentially an excuse by their general to inspire their fellow troops to try harder. Despite the bleak subject matter, Douglas was able to secure a $1 million budget—with a third reportedly going to him for portraying the lawyer who gives the accused a defense despite pretty much knowing that his efforts are in vain—and “Paths of Glory” came into being. The film was a resounding box-office flop but it was instantly hailed as one of the great war movies of all time—albeit one banned or censored in numerous countries for its anti-military tone—and it is one of those films whose power and resonance has only grown over the years. Kubrick and Douglas would collaborate again when Douglas brought Kubrick in to replace Anthony Mann as the director of the epic “Spartacus” (1960) after a week or so of shooting but the collaboration this time was less felicitous—although the film is easily the best and most artfully conceived of all the epic productions of that era, the two clashed over control issues to such a degree that Douglas vowed never to work with Kubrick again.

As the Sixties came around, Douglas began branching off into a wide variety of film genres. “Strangers When We Meet” (1960) was a suburban-based melodrama in which he and Kim Novak play neighbors who wind up having an affair. There were the Westerns “The Last Sunset” (1961) and “Lonely Are the Brave” (1962)—the latter was often described by Douglas as his favorite of all his films. “Two Weeks in Another Town” (1962), sort of a spiritual continuation of “The Bad and the Beautiful,” found him as a washed-up actor trying to restart his career after spending three years recovering from a nervous breakdown. He turned up in John Huston’s offbeat mystery “The List of Adrien Messenger” (1963), though to say as who would ruin the film’s bizarre gimmick. He collaborated with rising director John Frankenheimer for 1964’s “Seven Days in May,” in which he play a military official who happens upon evidence that the Joint Chiefs of Staff (led by Lancaster) are plotting a coup against the president for signing a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union. He also purchased the rights to Ken Kesey’s celebrated counterculture novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and starred in a Broadway adaptation that lasted for five months. Over the next several years, he tried to get a film version done but when he was unable to pull it off, he passed the rights on to son Michael, whose 1975 version was an Oscar-winning hit.

Although he continued to retain his star status over the years, the films were getting a little dodgier, though you rarely ever saw him sleepwalking through anything in exchange for a paycheck. There were numerous Westerns, such as “The Way West” (1967), “The War Wagon” (1967), “There Was a Crooked Man. . . “ (1970), “Scalawag” (1973) and “Posse” (1975), the latter two of which he also directed. In 1977, he moved into horror with “Holocaust 2000” (1977), a genuinely insane Italian knock-off of “The Omen” that is almost beyond description, and followed that up with the cult favorite “The Fury” (1978), Brian De Palma’s audacious followup to “Carrie” that saw him trying to rescue his son from a covert organization hoping to exploit his incredible telekinetic powers. Douglas would reunite with De Palma in 1980 for “Home Movies,” an odd and often-overlooked comedy in which he delivers a funny performance as a film school instructor imparting his dubious wisdom upon his students. And yes, there were movies that not even his still-considerable presence could save, such as the ridiculous sci-fi thriller “Saturn 3” (1980) and “The Final Countdown” (1980), a cheesy time-travel thriller in which he plays the captain of the U.S.S. Nimitz who, along with his crew, travels back to Pearl Harbor before December 7, 1941 and is torn over whether or not to stop the attack he knows is coming.

For the remainder of his career, which ended with his retirement after the 2004 drama “Illusion,” Douglas worked less and did more television parts (including an episode of “The Simpsons”) but still demonstrated his undeniable screen magnetism. He was good in a double role in the quiet Australian Western “The Man from Snowy River” (1982) and reunited one last time with Burt Lancaster for the cheerfully silly comedy “Tough Guys” (1986), in which they play a couple of guys trying to adjust to the changes in the world after spending 30 years in prison. He turned up in a funny cameo as Sylvester Stallone’s dying father in “Oscar” (1991) and as the dying patriarch of a largely avaricious family in the comedy “Greedy” (1994). “Diamonds” (1999) was a largely dreadful drama in which he plays an elderly former boxer, largely incapacitated by a stroke, who convinces his estranged son (Dan Aykroyd) and grandson to help him find diamonds that he supposedly his decades earlier after throwing a fight, a journey that culminates with the three of them visiting a brothel run by Lauren Bacall. “It Runs in the Family” (2003) was another tale of differing generations coming together that was of interest because it marked the first time that he and son Michael appeared in a movie together—his grandson Cameron and his first wife, Diana Douglas, turned up as his wife. (They divorced in 1951 and he went on to marry second wife Anne Buydens in 1954, a union that lasted until his death) In 1988, he wrote his autobiography, “The Ragman’s Son,” and proceeded to write another ten books between then and 2014.

Over the years, Douglas would receive any number of awards celebrating both his film career and philanthropical efforts ranging from an Honorary Oscar in 1996 to a Kennedy Center Honor in 1994 to the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1981. He has also been celebrated as one of the people who helped bring an end to the Hollywood blacklist of talent accused of having Communist ties when he insisted on giving writer Dalton Trumbo full credit for the screenplay for “Spartacus.” At the same time, Douglas was also connected with allegations that, while never leading to any formal charges, would continue to be whispered about for decades. During the filming of “Young Man with a Horn,” actress Jean Spangler, who had a bit part, disappeared and when her purse was found, it contained a note addressed to “Kirk”—Douglas denied any involvement with her still-unsolved disappearance while friends said that she was pregnant and had been talking about getting a then-illegal abortion. It has long been rumored that in 1954, he invited actress Natalie Wood, then 16, to his room at the Chateau Marmont hotel for an audition and proceeded to brutally rape her. There were no charges—her mother supposedly convinced her not to report it for fear that doing so would harm her potential career in an industry where he was among the biggest names—but it was not a secret either and as late as 2018, when he appeared at the Golden Globes, there were complaints about his presence.

Now he is gone and with him goes one of the last connections with the Golden Age of Hollywood, a time when an actor of his caliber and popularity would use those traits to put together challenging and ambitious projects instead of simply looking for the biggest paycheck. On the screen, he could work in any genre—action, comedy, Westerns, even a viking film (1958’s “The Vikings”)—and succeed more often than not. Off the screen, it seemed as if he could overcome most any obstacle as well, managing to survive a 1991 helicopter crash and a severe stroke in 1996. He may no longer be with us but the artistic legacy he leaves behind is one that will provide future moviegoers with an astonishing array of films to explore. One pro tip—don’t start with “The Villain.”