I don’t know when production began on John Frankenheimer’s “The Fourth War,” but its timing is interesting: In period, it’s the last Cold War movie, and in spirit, the first post-Cold War thriller. The suspense centers on whether someone will screw up detente. Some of the new geopolitical dialogue sounds a little strange to the ear, as when an American colonel stands near the border between West Germany and Czechoslovakia and fearlessly barks, “What we have here is primarily a public relations role!” No specific reference is made in the movie to the Gorbachev era, but it’s clear that the primary purpose of the American border patrols is to avoid shooting themselves in the foot.

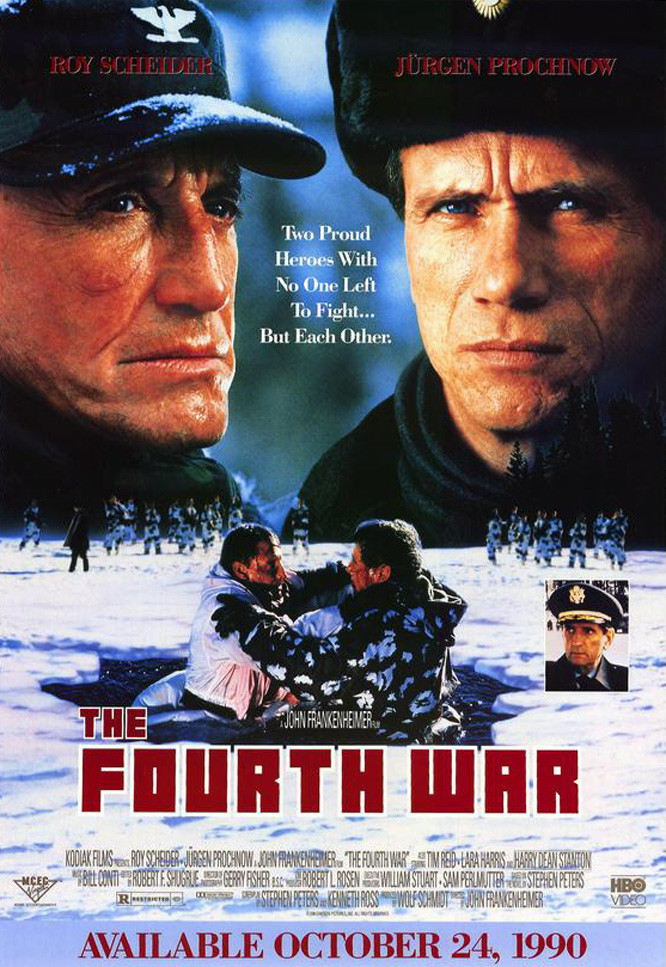

That prepares the canvas for the arrival of Col. Jack Knowles (Roy Scheider), who has been the Army’s loose cannon and maybe its loose screw ever since the war in Vietnam. Knowles has so many decorations you can’t see his uniform, but he has never been known for his sound judgment in command positions. The Army has posted him as far away from trouble as possible – Guam was a typical duty – but now he has finally been returned to a front-line command. It has something to do with how an old Vietnam buddy, Gen. Hackworth (Harry Dean Stanton), has faith that he has regained his senses.

The faith is premature. Knowles is a hothead and a lone wolf, and his war, as they like to say in the movie ads, is not over. It is his misfortune, and perhaps the misfortune of the entire planet, that he has been positioned on the Czech border exactly opposite an equally short-tempered Russian named Col. Valachev (Jurgen Prochnow). On the first day of his new command, Knowles has to stand by impotently and watch as a would-be refugee is shot down within yards of freedom. Then Valachev hovers overhead in a Soviet helicopter and, in Knowles’s words, “sticks his rockets in my face.” Nobody sticks his rockets in the face of Col. Jack Knowles, and before long Knowles is sneaking across the border on unauthorized solo missions to sabotage enemy installations and stick his own rocket, so to speak, in Valachev’s face. Knowles’s dangerous activities do not go unnoticed by his second in command (Tim Reid), and there are reprimands from Hackforth back at division headquarters, but now Valachev has engaged himself in the dangerous game, and the two men refuse to back down. There are moments when the possibility of accidental war seems very real.

“The Fourth War” is essentially a psychological study of a man coming apart at the hinges. Knowles, played by Scheider, is an embittered, alcoholic loser who was a hero once, a long time ago and far away. Now appropriate conditions no longer exist for his kind of hot-dog heroism. Although the movie centers on well-made action scenes and contains a couple of tidy surprises, its strength comes from the portrait of this soldier on the edge. Scheider has a role not unlike Laurence Harvey’s in Frankenheimer’s masterpiece “The Manchurian Candidate.” He is a victim of his programming. He reacts to Soviet troops the way Harvey reacted to a hand of solitaire.

The supporting performances are where the movie’s sanity resides.

Reid, as the second in command, plays the role as a textbook officer who knows he’s on thin ice and does everything by the book. Stanton, as the general, has a long, angry speech in one scene, and as he slams his words into Scheider’s silence, we’re reminded of what a powerful actor he is.

Movies like “The Fourth War” are a reminder that Hollywood is running low on villains. The Nazis were always reliable, but World War II ended 45 years ago. Now the Cold War is winding down, and just when “Lethal Weapon 2” introduced South African diplomats as bad guys, de Klerk came along to make that approach unpredictable. Drug dealers are wearing out their welcome. Bad cops are a cliche. Suggestions?