John Frankenheimer’s “The Horsemen” is about the most dangerous game in the world, which, in case you don’t have your Guinness Book of World Records handy, is buzkashi. It is played in Afghanistan, and the object is to pick up a headless goat at full gallop (you are galloping, not the headless goat) and carry it all the way around an enormous field and back to the charmed circle.

While you are doing this, the other players are trying to snatch the headless goat away from you, and they are whipping you and your horse with short, mean whips. It takes a real man to play buzkashi, a point that (in case it doesn’t occur to you) the dialog makes maybe a dozen times.

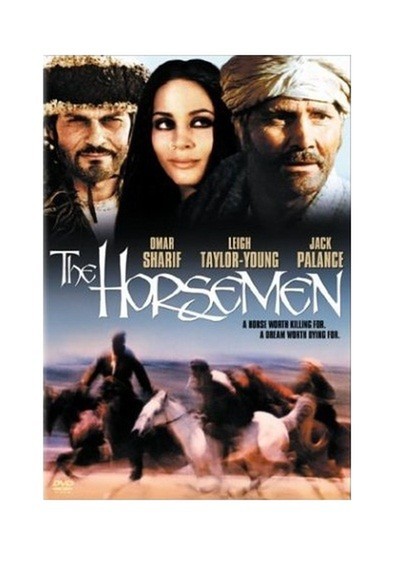

The real man this time is Omar Sharif, he of the deep-set, melancholy eyes and the face of courage and suffering. He lives in the 20th Century, and yet he is obsessed with the greatness of past buzkashis. His father (Jack Palance) was the greatest buzkashi player in the province, so it is said, and if the son can win the great buzkashi that has been decreed by the emperor to be held in the capital city, his prize will be the father’s white stallion. That is no mean reward; the white stallion is valued above everything else in the province, including women, children and Land Rovers, and men are willing to kill for it.

All of this is Frankenheimer’s preparation for a long and spectacularly photographed buzkashi, which is violent, bloody and desperate. There hasn’t been a sustained action sequence on this scale since the chariot race in “Ben Hur,” which you may be reminded of. But Frankenheimer’s movie isn’t really about the buzkashi itself, but about the character of the men who play it.

After he breaks his leg and is meanly treated by the other players, Sharif does somehow fail to win the buzkashi (although, wouldn’t you know, a teammate leaps aboard the prize white stallion and does win.) Filled with remorse, Sharif determines to return home by the old mountain road, where, if I recollect correctly, the days are filled with the heat of a thousand suns and the nights are cold enough to give pause to a brass monkey.

This endurance test is designed to convince Sharif that he is still a man, still worthy of his father’s honor, still deserving of the prized great white stallion, etc. After he wards off a couple of murder attempts by his trusted valet (who covets the prized great white stallion), his broken leg becomes infected and has to be chopped off with an ax by a mountain veterinarian.

Sharif stuffs a hanky in his mouth, grits his teeth and bears it. Then he binds the stump, sticks it into his boot and rides off nonchalantly so no one will know he’s lost a leg. If he’s not convinced by now that he’s still a man, worthy of his father’s honor, etc., I don’t know how we’re going to bring him around.

“The Horsemen,” as you may be gathering, is a film out of its time. We live in an age of movie antiheroes, when the word “losers” in a title sells more tickets than the word “sex,” and it is a little hard for us to sympathize with a man who would deliberately seek out the heat of a thousand suns, etc., when we pine for Lincoln Park whenever the temperature hits 85. The character is basically unlikely (even though buzkashi may indeed still be played by men like gods in Afghanistan), and neither John Frankenheimer’s spare, heroic direction nor Claude Renoir’s spectacular photography can quite bring this horseman to life.