Popeye Doyle, the New York narc created by Gene Hackman in “The French Connection,” was the most compelling of characters, a man driven by violent hungers that had little to do with his job as a cop. He needed the violence, maybe, to survive the toughest beat in town. He had such presence, such a capacity to explode, that when he ran a bust on a bar, the patrons — pretty tough themselves — were actually intimidated. Popeye was something unique among film characters, and Hackman deserved the Oscar he won for the performance.

But whatever Popeye was, he wasn’t a clown, and that’s what he comes disturbingly close to looking like in “French Connection II,” John Frankenheimer’s continuation of the story. This isn’t really a sequel, it’s a fresh start with the same character, and it’s not a rip-off of William Friedkin’s 1970 film. It leans over backward, indeed, to avoid yet another version of that car-train chase that inspired so many imitations. Frankenheimer apparently wanted to get inside Popeye, to understand him more completely. But if that was his purpose, then he made a mistake by moving the action from New York to Marseille.

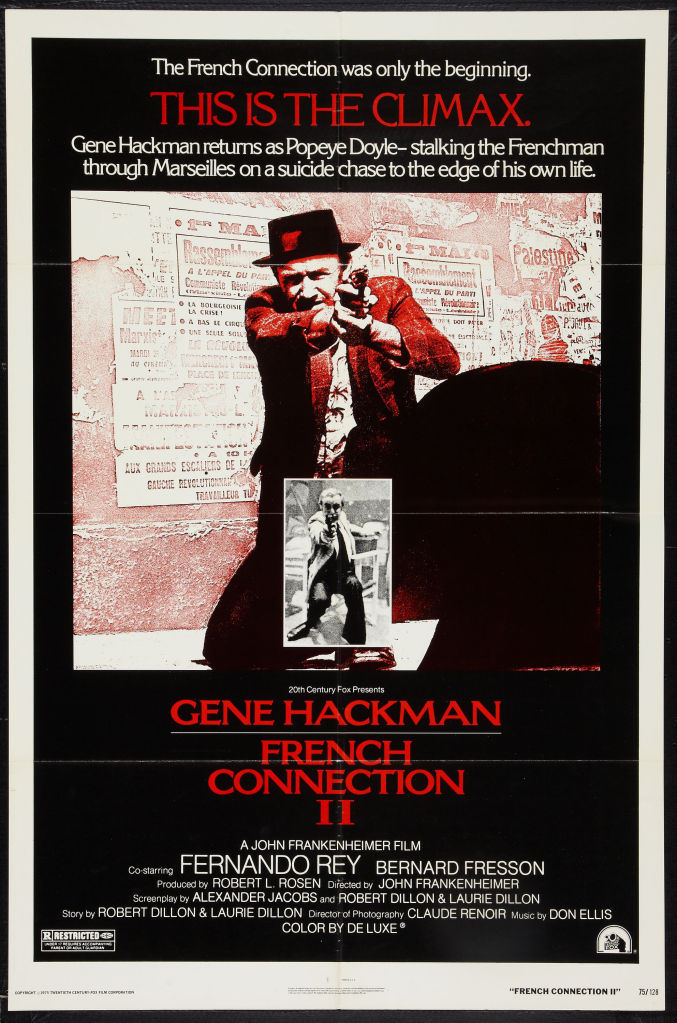

Frankenheimer obviously knows Marseille, and his portrait of the city is sharply seen. But it’s not Popeye’s city, and that’s the trouble. On his own turf, Popeye either ran things or knew what made them run. In Marseille, he’s hopelessly stranded — an awkward, confused, highly visible American with that silly little porkpie hat and about three words of French. He’s been sent to Marseille (very implausibly) to capture the Frenchman of the first movie, the master criminal of the heroin trade. But this far from home, he can barely function as a tourist, much less as a cop, so the movie shows him in a different light than the original Doyle.

He has conversations with the French that apparently are inspired by Mark Twain’s assertion, in ‘The Innocents Abroad,’ that anyone can understand English if it is spoken slowly enough and loudly enough. He has run-ins with local cops, who assign him a desk next to the men’s room and won’t let him carry his pistol. He plunges into the case with the grace of a beached whale, and in no time at all, he’s been kidnaped by the heroin smugglers. With exquisite irony, they keep him a prisoner by hooking him on heroin.

And then we get an extended central section of the film devoted to Hackman’s addiction and (after the French cops get him back) his cold-turkey ordeal. There’s a lot of good acting here by Hackman, who leaves no emotion unchurned, and there are good laughs in a virtuoso sequence (written by an uncredited Pete Hamill) in which he gets drunk and launches into a discussion of the New York Yankees with his uncomprehending guards. But the movie comes to a standstill. The plot, the pursuit, the quarry, are all forgotten during Hackman’s one-man show, and it’s a flaw the movie doesn’t overcome.

We find it a little difficult to get involved in the plot anyway, since it’s a bit confusing. I may be impenetrably dense, but I couldn’t figure out what was being carried around in the white flight bags that seemed so important (money, I guessed, but I wasn’t sure). And I was thrown off the pace by a scene in which Hackman, trying to order Scotch from a French bartender, has no luck.

Now every French bartender knows the English word “whisky,” thank heaven, because the French use the same word. So when the bartender didn’t understand, I figured he was deliberately playing dumb — especially since he inexplicably seemed to understand what Hackman was saying when he offered to buy the bartender a drink. It’s a trap, I thought. But it wasn’t. It was just a loophole.

Scenes like that, with the audience invited to laugh at Popeye’s discomfort, just don’t feel right. Here’s a guy whose competence, whose ability to function at a gut level, whose street instincts made him a new and original kind of movie cop. And now he’s being used for comic relief and stripped of his dignity. I kept wondering why “French Connection II” hadn’t stayed on location in New York, where Popeye belonged, instead of going to Marseille, a place it’s patently clear no sane superior would ever send him.

The movie does have a nice sense of place, though, and the Hackman performance, and a final sequence in which Popeye runs and runs and RUNS and finally nails the Frenchman in a tight little shocker of an ending. If Frankenheimer and his screenplay don’t do justice to the character, they at least do justice to the genre, and this is better than most of the many cop movies that followed “The French Connection” into release. It’s an indication, in a way, of how certain kinds of stock characters have been remade in the last five years. After “The French Connection” and “The Godfather,” with their deeply felt under standing of cops and gangsters, the old stereotypes just won’t do anymore. They’re silly and we’ve seen the real thing.

]]>