Blog Posts That Mention Amy Irving

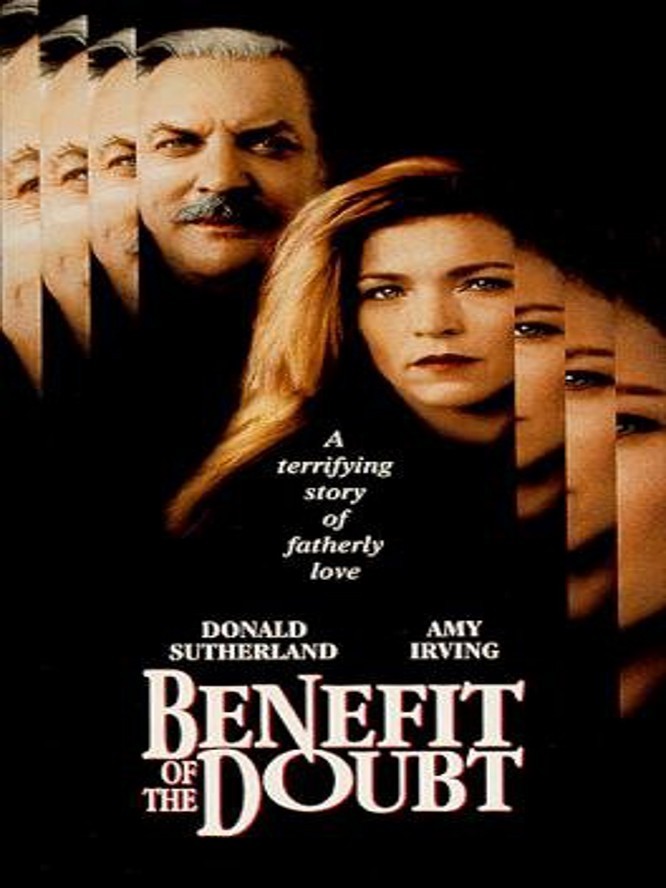

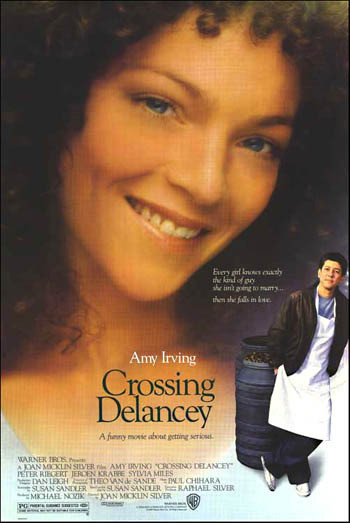

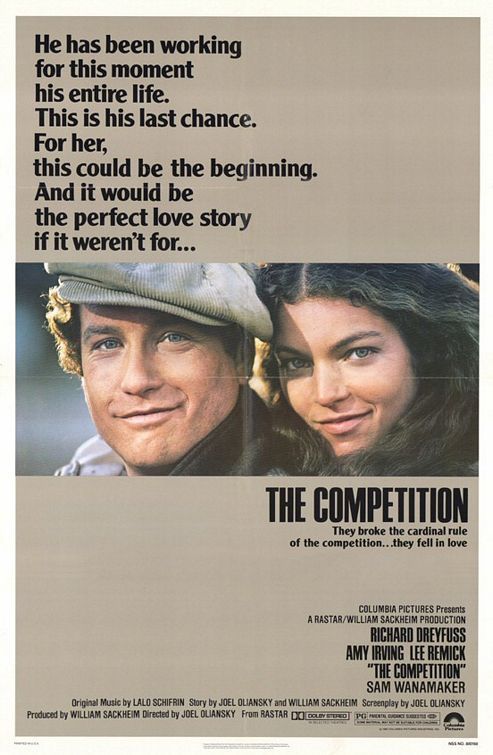

Sex, Love and Pickles: Amy Irving, Peter Riegert and Susan Sandler on “Crossing Delancey”

Marya E. Gates

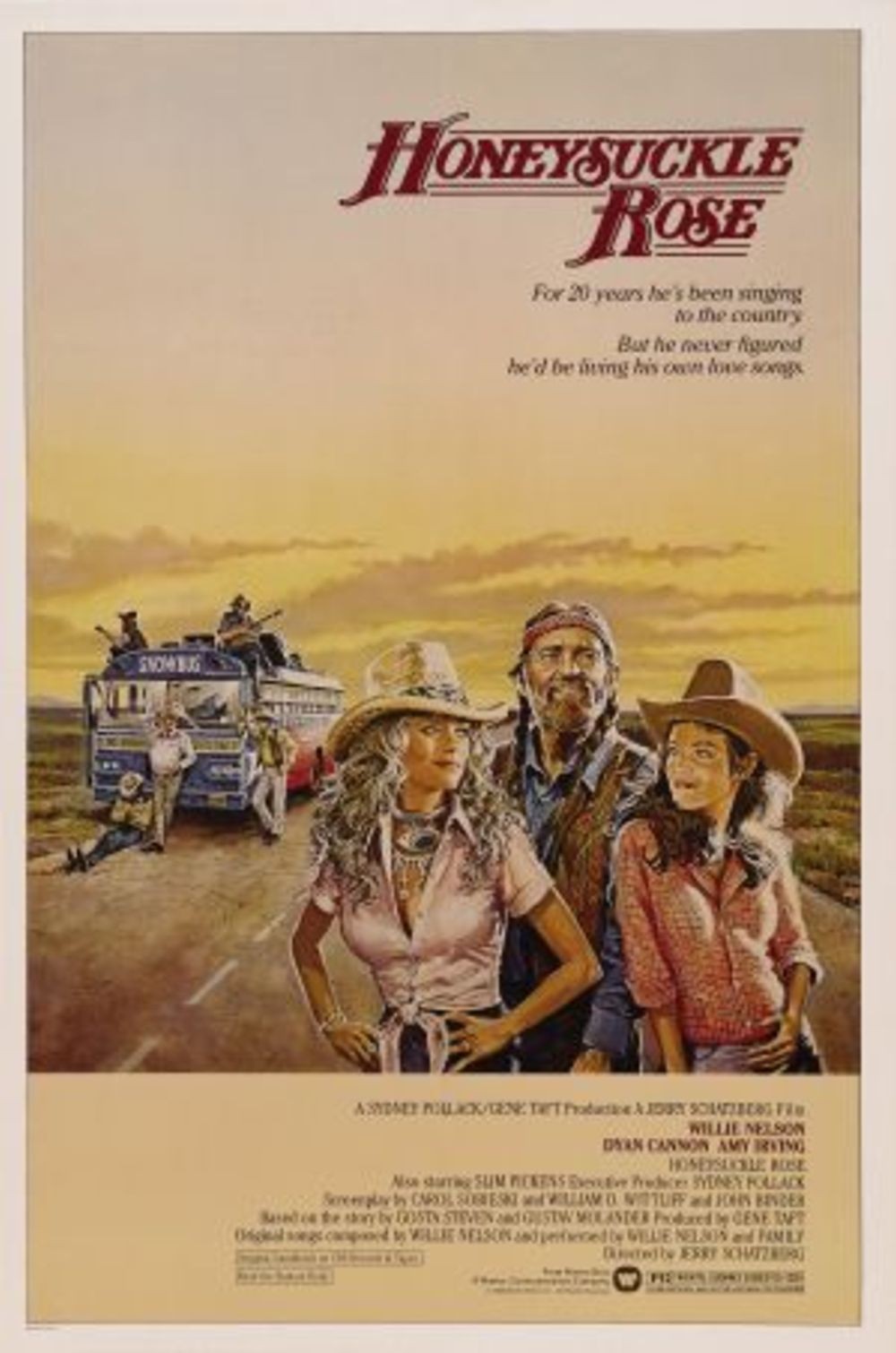

Happiness is being on the road again

Roger Ebert

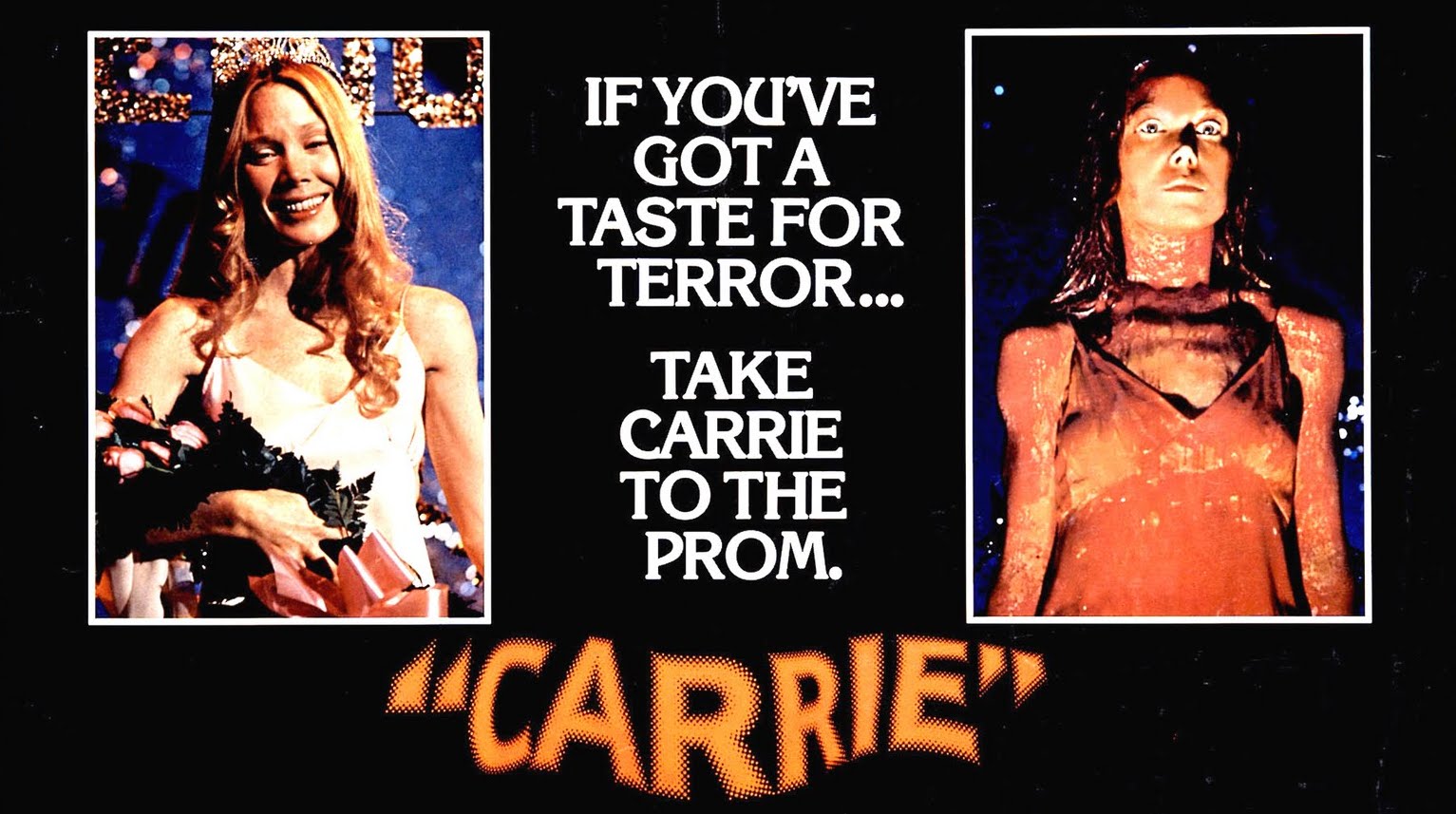

De Palmania!

Jim Emerson

Women Writers Week 2025: Table of Contents

The Editors

February 2025 Blu-Ray Guide: “Wicked,” “Nosferatu,” “Here,” “Heretic,” More

Brian Tallerico

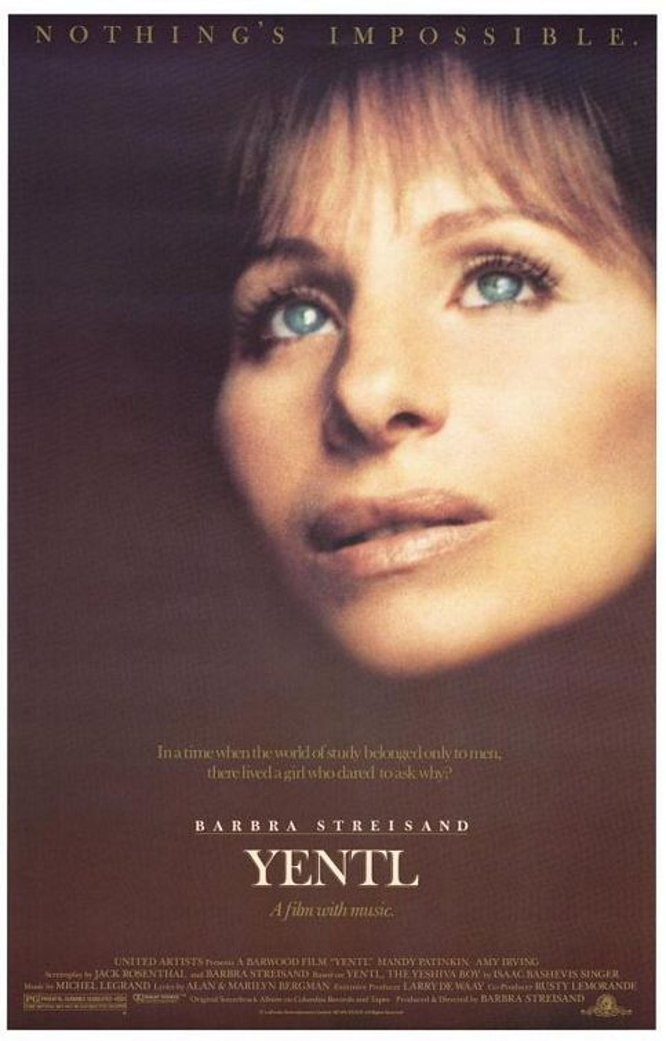

Bright Wall/Dark Room June 2023: Yentl and the Three-Quarter Profile by S. Brook Corfman

The Editors

Highlights of the 2023 TCM Film Festival

Laura Emerick

My Mother’s Stories: Michael Koresky on Films of Endearment

Sheila O'Malley

David Fincher’s Mank Leads 93rd Oscar Nominees with 10

Susan Wloszczyna

Beyond the Lines: Joan Micklin Silver, 1935-2020

Matt Zoller Seitz

Celebrating the Artifice: Laurent Bouzereau on Spielberg, Hitchcock, De Palma and More

Matt Fagerholm

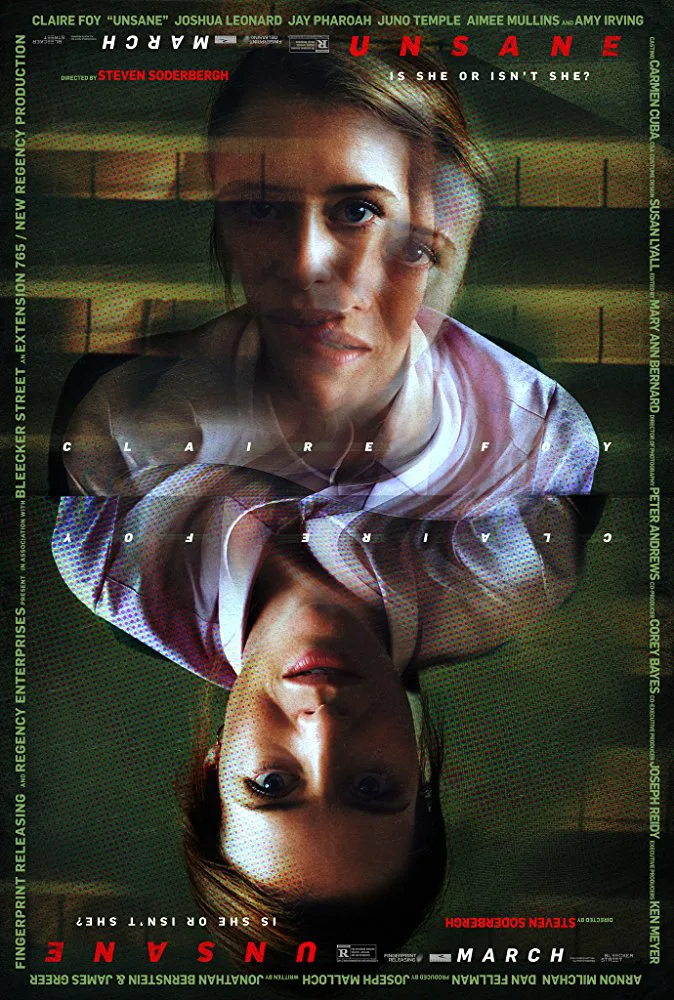

2018 Winter Movie Preview: 25 Films We’re Excited About

Nick Allen

A Composer For All Seasons: On the Range of John Williams

Charlie Brigden

If Only They Knew She Had the Power: Brian De Palma’s “Carrie” Turns 40

Peter Sobczynski

Book Excerpt: Psycho-Sexual: Male Desire in Hitchcock, De Palma, Scorsese, and Friedkin by David Greven

The Editors

Brian De Palma’s Films, Ranked

Peter Sobczynski

Opening Shots: ‘Greetings’

Jim Emerson

Tracing the image #2: The rebirth of ‘The Descent’

Jim Emerson

Can a movie ruin a good review?

Jim Emerson

Melanie Griffith puts heart into `Stormy Monday’

Roger Ebert

Happiness is being on the road again

Roger Ebert

Popular Reviews

The best movie reviews, in your inbox