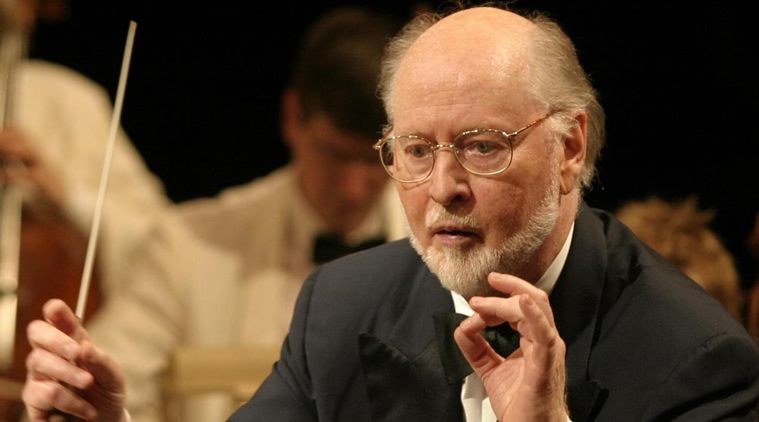

Now that we’re thick into the holiday shopping season, we know for sure that we’ll soon be getting that greatest of gifts, a new score by John Williams. On December 15th, the behemoth release that is “Star Wars: The Last Jedi” opens, and with Williams’ predictably great work on “Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens” leaving us expecting nothing less than a masterpiece it’s undoubtedly the most-anticipated soundtrack of the year. But occasionally you seem to hear people espousing the claims that this is all Williams does, that he is a one-trick pony of bombast and adventure.

Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. But don’t be hasty, there’s plenty of factual evidence to back this up from throughout Williams’ career, of which there are many highlights that have nothing to do with Wookies, superheroes, or aliens. Jazz has been of a particular interest in Williams’ life—he was born in 1932 to mother Esther and father Johnny Williams, a jazz musician who not only played in bands for folk like Benny Goodman but also on scores such as George Duning’s “From Here To Eternity” and Leonard Bernstein’s only film score, the classic “On The Waterfront.”

Williams Jr. called himself “Johnny” in his earlier years, and after a stint in the USAF attended Julliard in New York City, where he freelanced as a jazz pianist before finding himself in LA playing for Henry Mancini on television show “Peter Gunn” (that famous riff everybody knows was played by Williams). Williams’ early composing was often for ‘60s comedies such as “Not With My Wife, You Don’t!” and “How To Steal A Million.” As his stature grew after Oscar nominations for “Valley of the Dolls” and “Goodbye, Mr. Chips,” he found himself working on much more interesting fare on which he could lay his jazz influence. Deadpan detective yarn “The Long Goodbye” was one of two collaborations between Williams and director Robert Altman, and, like the film itself, the music was a delightful metatextual commentary on the film noir gumshoe drama. The title song appeared multiple times across the film in varying arrangements to interact with the characters, even at one point appearing as supermarket muzak.

The 1970s saw Williams collaborating for the first time with Steven Spielberg for “The Sugarland Express” (1974), in which Williams gave a large role to iconic jazz harmonica player Toots Thielemans. In the following year, alongside his breakout score for the next Spielberg epic, “Jaws,” Williams composed a fine jazz-infused score for the Clint Eastwood thriller “The Eiger Sanction,” Eastwood himself a noted fan of jazz. In the same period, he was also scoring Westerns such as the John Wayne picture “The Cowboys,” Burt Reynolds vehicle “The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing,” and Arthur Penn’s “The Missouri Breaks,” as well as winning his first Oscar for adapting Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick’s songs and score for “Fiddler On The Roof.”

It was around this time that he also began to show his aptitude for horror scoring. Obviously, this would come to an explosive head with the aforementioned “Jaws,” but one of his earlier scary scores was for the second of his Altman collaborations, 1972’s “Images.” A psychological thriller starring Susannah York may not sound like obvious territory for the composer, but he wrote a brilliant avant-garde score that is still harrowing to this day, to the point where Spielberg originally used it as temp-track music for his shark picture until Williams convinced him he needed a different direction. The end of the decade saw Williams create some wonderfully distinctive music for horror movies; another crack at the fin came with “Jaws 2,” which is arguably as strong a score as the first, while he brought a romantic flourish to a certain iconic Count with John Badham’s “Dracula,” which mixes his European romantic sensibilities with the wonderful gothic fury of James Bernard.

But his strongest entry in the horror stakes was for Brian De Palma’s “The Fury.” A tragedy-tinged science fiction horror melodrama with Kirk Douglas and Amy Irving, the film is directed with De Palma’s usual panache, but Williams is the MVP, his stirring under-the-surface creeping main title melody reflecting the explosive brain signals of the children in the film. The same year also brought his superhero opus “Superman” which remains the gold standard for the genre to this day, and in a way it’s key to his ongoing success outside of blockbusters. While the themes for the man of steel are triumphantly heroic and thrillingly romantic, there is a great deal of human drama in the film that both Williams and Richard Donner knew were the heart of the film and the character. Prior to the destruction of the planet Krypton, Williams gives angelic voices and huge powerful chords to the advance civilization, but when Jor-El and Lara say goodbye to the infant Kal-El (“You will travel far, my little Kal-El … “) he uses a wonderfully emotional string piece to underscore the honesty of the scene, a color which is inherited by the scenes in Smallville. The wistful Copland-esque motif not only brings a sense of nostalgia but also decency, through Jor-El and his death and eventually Clark himself when he leaves.

It’s this kind of musical quality and emotional content that Williams has been quietly been needling at since the beginning of his career. Interestingly, one of his best dramatic scores was a relatively early work in Delbert Mann’s 1970 TV movie “Jane Eyre.” It’s a fairly respectable adaptation of Charlotte Bronte’s groundbreaking novel, but Williams’ score is incredibly intricate and emotionally resonant, with the romantic title theme easily up there alongside more famous pieces such as “Princess Leia’s Theme.” His dramatic work over the years has been hailed as powerful, notably for his collaborations with director Oliver Stone (“JFK,” “Born On The Fourth Of July,” “Nixon”) but it’s for some of the quieter dramas that much of his best music resides, such as the wonderful score for Lawrence Kasdan’s “The Accidental Tourist,” or the Robert De Niro/Jane Fonda romance “Stanley & Iris.” And, of course, his instantly recognizable score for “Schindler's List” remains a masterpiece.

In the 21st century, Williams has continued this even into other genres with the sublime science fiction fairytale “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” and the comedy “The Terminal.” And while he has “slowed down” Williams has produced gems such as “Munich,” with a pleasingly effervescent variation on the “moaning woman” score cliché as conceived for Hans Zimmer’s “Gladiator,” or the highly-praised Spielberg biopic “Lincoln,” which received a stunning but understated score (three years prior he had also composed “Air and Simple Gifts” for another Presidential moment, the inauguration of Barack Obama). And then there was “War Horse,” perhaps his masterpiece of the decade so far where he was able to illustrate his great love of British classical music, particularly the work of Ralph Vaughan Williams. “War Horse” contains such a rich and lyrical array of orchestral colors and two beautiful themes that again show that Williams has no equal. And even with another journey to the world of Luke Skywalker almost upon us, there’s another score coming from Williams that is his Golden Globe-nominated work for “The Post,” Spielberg’s drama based on the leaking of the Pentagon Papers. That film is sure to provide prime material for Williams to display his consistently interesting sensibilities.

Put simply, Williams’s musical talent is a lot more than just “Star Wars.” Of course, I didn’t even mention “Harry Potter.” “Or Indiana Jones.” Or “Jurassic Park” …