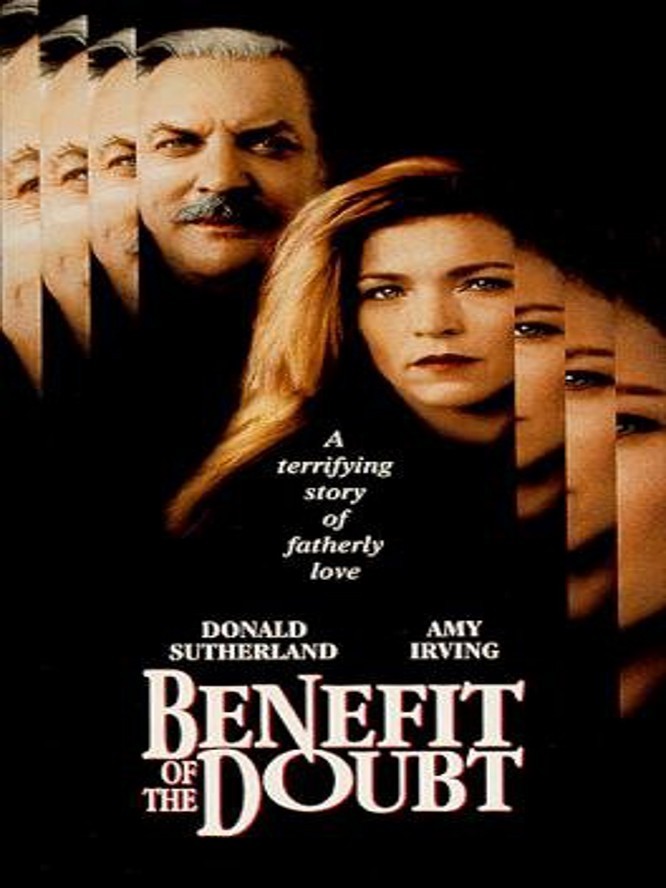

“Benefit of the Doubt” blows a lot of its suspense in the opening title sequence, as we hear Donald Sutherland testifying before a parole board, “The strength of this country lies in the strength of its families.” Since the movie is billed as a thriller, and since his voice sounds sanctimonious but hollow, we know at once he’s not sincere; almost before we see him, we know he’s the movie’s bad guy.

Too bad, because a more interesting movie might have resulted if one of the screenplay’s unrealized ideas had been used. That’s the possibility that the Sutherland character might, in fact, be innocent. As we meet him, he’s being released on parole after serving a 22-year sentence for murdering his wife. The key testimony against him at the trial came from his daughter (Amy Irving), then a child, now a single mom working as a waitress in a strip club.

Did Irving tell the truth in her testimony? The movie tries to build up evidence that she might have been “guided” by a defense attorney. Now, with Sutherland out and headed her way, she’s in terror that he might strike again.

“I won’t forget this,” he told her as he was led off to prison.

Since we know with some certainty that he was in fact guilty, the accuracy of her testimony is a blind alley. We know he killed, and we suspect he’ll kill again. But think how much more involving the movie would have been if the first hour played it straight, pretending that Sutherland was unfairly framed, and that he is now prepared to forgive his daughter and start life again. That would make the movie’s later developments truly frightening, instead of drearily inevitable.

“Benefit of the Doubt” is a movie without those kind of smarts.

Filmed in and around the Grand Canyon, it puts together sequences as if they were film school exercises. One doesn’t lead into another. We are asked, for example, to believe it when dad slithers into bed with his sleeping daughter, and she mistakes him for her dead boyfriend.

Uh-huh.

And what about an extended chase scene in which Irving and her son (Rider Strong) walk miles through the wilderness to get to a lake where they have the keys to a houseboat. On board the boat, fearing Sutherland could still be on the loose, they should obviously go out into the middle of the lake and keep their eyes open. But not in an Idiot Plot like this, where the kid is left home alone.

Things get even more incredible. Irving and her child climb into one speedboat, Sutherland climbs into another, and they chase each other around the lake in a painfully contrived scene, before – get this – grounding the boats so they can resume their chase over the rocks.

There’s hardly a moment in “Benefit of the Doubt” when we can believe the events on a psychological level, or even on the level of a manipulative thriller. The performances are good – Sutherland is creepy as he recites his pious platitudes, and it’s fun to see Irving in a down-home blue collar role again, a reminder of her work in Willie Nelson’s “Honeysuckle Rose” (1980). But the story’s so phony it undermines everything.