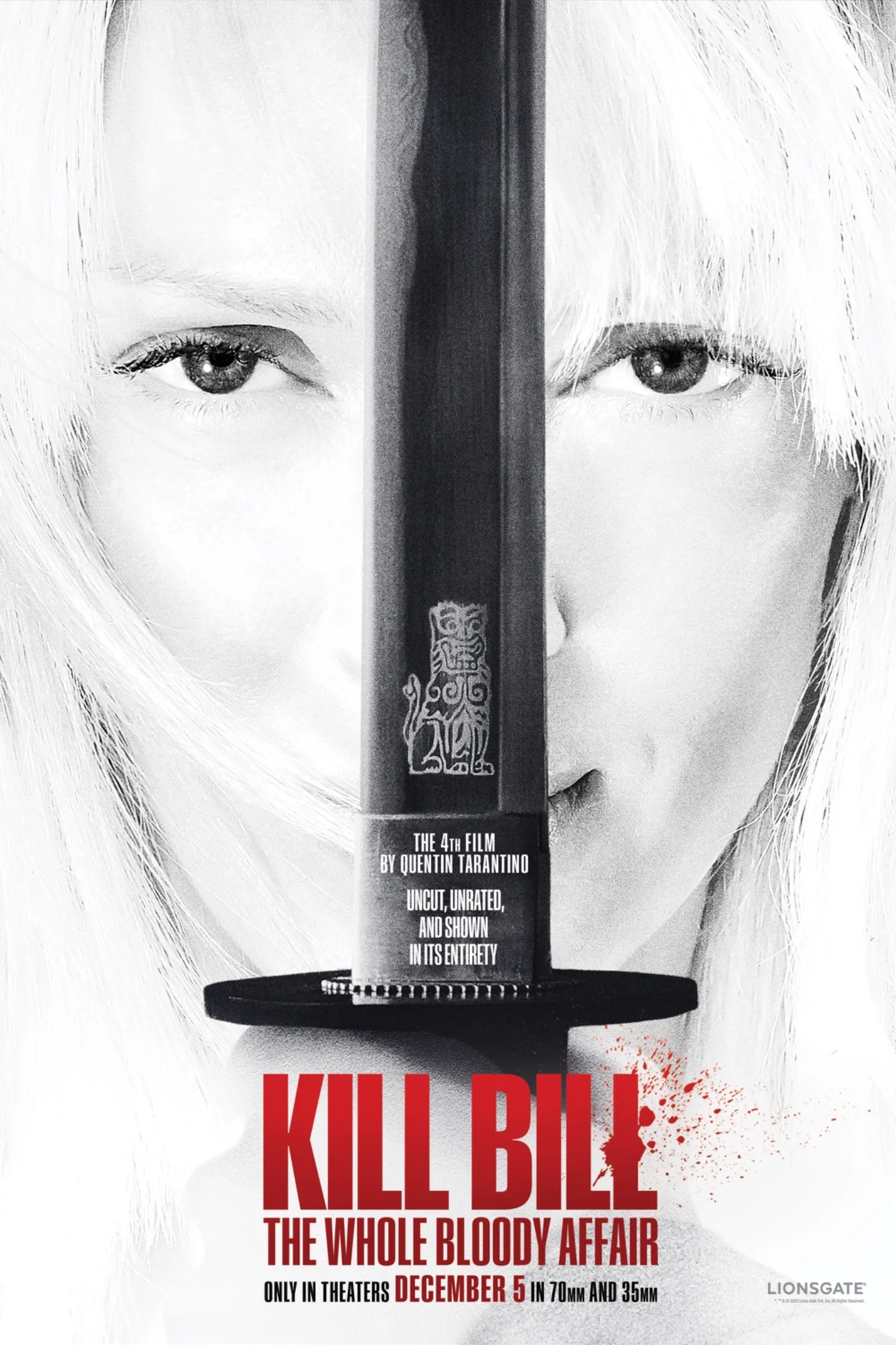

Quentin Tarantino’s “Kill Bill” stars Uma Thurman as an assassin left for dead on her wedding day who seeks revenge against her would-be murderers, a motley gang that includes her mentor-lover Bill (David Carradine) and his four deadliest assassins (Vivica A. Fox, Lucy Liu, Michael Madsen, and Daryl Hannah). His original cut ran four hours. Rather than force the writer-director to shrink the running time, the film’s releasing studio, Miramax, released “Kill Bill” as a theatrical two-parter: 2003’s “Volume One” and 2004’s “Volume Two.”

Reviews were mixed, and the industry was indifferent to it. But it was a worldwide financial success that opened up the second half of his career, which has been dominated by operatic and melodramatic historical fantasies like “Inglourious Basterds,” “Django Unchained,” and “Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.”

“Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair” is not just the longest Tarantino movie but arguably the most Tarantino movie. It’s undoubtedly his most pop-culture-obsessed movie, which is saying a lot about a director whose breakthrough feature, 1994’s “Pulp Fiction,” staged a key scene in a restaurant that was like Planet Hollywood for Turner Classic Movies subscribers. Seen in two parts or as a whole enchilada, it’s a lot to process, even for a viewer who likes a lot of the same stuff Tarantino is into. The aesthetic blends kung fu and Yakuza films, Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns, cruel and outrageous 1970s grindhouse cheapies, and anime/manga. Tarantino has said many times over the last two decades that he considers “Kill Bill” a single, long movie. The release of “Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair” proves him right. (Spoilers from here, because the movie is 22 years old.)

An early version of “The Whole Bloody Affair” premiered at Cannes 2006 and has been shown in Tarantino’s Los Angeles repertory theaters, but this is the first time it has received an official commercial release. It should be considered the definitive version in the future, unless Tarantino decides to re-edit it yet again.

Here, he slightly tweaks both “volumes,” stitches them together around a 15-minute INTERMISSION card, and restores previously deleted material that general audiences have never seen. The most striking is a ten-minute-longer flashback to the childhood and adolescence of Liu’s character, assassin turned Tokyo gang boss O-Ren Ishii, who was traumatized and exploited by the pedophilic gang boss who slew her parents, but survived to exact revenge 11 years later. The animated segment is so long that it sometimes plays as if a chunk of a different film (a spinoff prequel, maybe) that’s been inserted into the present-tense journey of the Bride, who wants to kill the people who snuffed out her wedding party and, she believes, ended her pregnancy.

There’s also a small but very important change at the end of the first half. “Volume One” revealed that the daughter was alive and in the custody of Bill, and had a name: B.B. (Perla Haney-Jardine), perhaps to persuade viewers to come back for “Volume Two.” This cut removes that bit of information, so it’s much more powerful when The Bride finds out at the same time we do. What was already a more emotionally complicated ending than we might’ve expected going in becomes even more fraught. And it gives one of the running saga’s running themes — men’s exploitation of women — more substance.

With more than twenty years’ distance, it’s easier to see, practically feel, the personal connections between the director, the star, and the material—especially after all the reporting on Tarantino’s long-standing symbiotic relationship with Miramax boss and serial sex offender Harvey Weinstein, as well as Tarantino’s knowledge of Weinstein’s crimes before, during, and after the production of the Kill Bill movies; and Thurman’s 2023 revelation that, during the shoot, Tarantino pushed her to drive a car into a tree in a misguided attempt at cinematic authenticity, causing severe injuries that she still deals with. During the beginning of the Me Too period, Tarantino belatedly apologized for not speaking out about the crimes of his chief patron Weinstein, which he was aware of. The post-wreck rift between him and Thurman has apparently been mended (they collaborated on a post-credits animated short for this release).

The real-life backstory may intrude in early scenes of Bill being photographed as a faceless but menacing puppeteer rarely seen above the neck (like how the comic strip Doonesbury represented U.S. presidents). It’s a multi-purpose image that can stand in for Tarantino’s influence over all of his actors; the looming presence of Weinstein over Tarantino financially and Thurman personally (she said Weinstein tried to sexually assault her a few years before he green-lit Kill Bill); and Thurman’s mixed feelings about Tarantino, an artistic partner in theory, but not so much in fact, due to the power imbalance in industry influence. Lots of entertainment legends have biographies that intrude negatively in fans’ minds while watching their work, such as Alfred Hitchcock’s cruelty toward some of some of his leading ladies, John Landis’ responsibility for the deaths of three people during the production of “Twilight Zone: The Movie,” Roman Polanski admitting to statutory rape; the legions of actors accused of sexual misconduct, and reports that Tarantino has physically abused actresses during several film shoots. (Bill ponders whether he’s thought of as a sadist.)

Incredibly, the interweaving of the story itself and the stories surrounding it don’t destroy the creation itself. At times the movie plays like a meditation on the last twenty years of Tarantino and Thurman’s lives, even though the laws of time and space make that impossible. Tarantino’s sheer command of craft and Thurman’s killer stare and death-sentence voice ensure that the story carries us along.

My near-total satisfaction with this version was a surprise to me. I remember mostly disliking “Kill Bill, Vol. 1,” save for the performances (Thurman’s especially) and specific technical and musical elements. One of my big problems was the pacing. I’m small-c catholic in my formal appetites and have been known to give four stars to movies so slow they’d put a snail to sleep. However, the two-part “Kill Bill” still felt interminable, like being trapped at a party by a cokehead record collector who won’t stop monologuing about the records on his Desert Island list. I might’ve called parts one and two the slowest and most disjointed revenge movies ever made. Turns out it was a context problem—and the problem was imposed from without, by marketplace considerations and the vulgarian sentiments of H.W.

With the whole tale laid end-to-end, the Bride’s odyssey now plays at a measured but relentlessly forward-moving pace. You get used to the steady rhythms of the storytelling pretty fast, so that when the O-Ren Ishi flashback, which felt like an endless digression to me watching “Volume One” for the first time, feels somehow shorter now, despite being substantially longer. By restoring the movie to its original, uncompromised state, which is as aggressively arty as commercial filmmaking is allowed to get, “The Whole Bloody Affair” is, ironically, the most inviting and fully satisfying version of the material. The bizarre Western gangster-martial arts film-noir Road Runner universe that Tarantino has whipped up feels more palpable. And, more so than any of his other movies (yes, really), this one earns the comparisons that Tarantino makes between his own work and true pulp writing that once was published in magazines and cheap paperbacks.

But the one-shot movie also evokes ancient texts and symbolic languages: the Old and New Testaments, Greek and Roman myths, folk songs, the Tarot deck, and gothic poems about characters haunted by loss. The numbered and titled chapters echo both Jean-Luc Godard’s nonfiction filmmaking collages, which were super-aggressive in their use of onscreen text, and the individual issues of a 10-part graphic novel. Each half has five chapters, and structurally, there a lot of mirroring effects, from the split-screen that’s sometimes employed in fight scenes to the way that specific motifs or story elements are placed opposite each other.

O-Ren Ishii’s origin story is about a child losing her parents, while the Bride’s is about a mother who thought she lost her baby before it could be born. Their stories are also mirrored by histories of childhood sexual trauma: O-Ren Ishi was trafficked, while the Bride has dialogue establishing that she was way, way too young to be in a romantic relationship with Bill, whose business ethos is somewhere between a pimp and a cult leader. There are mirrored performances by the same actor in once-scene roles: in part one, Michael Park plays a Texas lawman determined to catch the person responsible for the wedding day massacre; in part two, he plays the person who, in a grand sense, is responsible for it: Esteban Vihaio, a Mexican pimp who was a father figure to Bill. Elle Driver kills Bill’s brother Budd with a black mamba that springs from a suitcase of cash and bites him, killing him instantly, while The Bride kills Bill with Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique, in which the assailant contorts their hand like a rising cobra and “strikes” the target, killing him instantly. Bill nearly kills the heroine in the first half. His brother Budd nearly kills her in the second; \she symbolically resurrects herself twice, the first time from a coma, the second time from being buried alive.

But the biggest revelation here, and the greatest of satisfactions, is Thurman. Her rendition of the Bride in all of her contradictions is her finest work, and possibly one of the greatest lead actress performances in movie history–a merger of Bruce Lee-Clint Eastwood-style badass athleticism and the statue-like deployment of actresses in Ingmar Bergman’s films. Thurman is believable as a tall, tough Amazon who tears through enemies like a thresher in a wheat field. But she’s equally credible as a woman who has endured unfathomable suffering and has the physical and psychic scars to prove it. The shot of her breaking down in Bill’s bathroom as her daughter sleeps in the next room is so powerful that you can almost feel the movie buckle beneath its weight. The extended one-shot presentation strengthens what was already the best work of Thurman’s career.

Whatever your feelings about Tarantino and his work, this is a tremendous visceral experience, with radiant colors, slate-somber black-and-white, and geysers of crimson blood. To quote the end of another Tarantino film, it just might be his masterpiece.