Quentin Tarantino has found his actor in Christoph Waltz — someone who can speak Tarantinian fluently and still make it his own. When Waltz uses a self-consciously ostentatious word like “ascertain” (as in, “I was simply trying to ascertain…” — the kind of verbiage QT is as likely to put in the mouth of a lowlife crook as a German dentist, or a Francophile plantation slavemaster, for that matter), it sounds right. As someone to whom Tarantino’s dialog often sounds cliche-ridden and cutesy, it’s a pleasure to hear Waltz saying the words in character rather than simply as a mouthpiece for the writer-director.

Oh, stop. This isn’t sounding the way I want it to.

When I first sat down to write about Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained” I kept discarding paragraphs like the one above because they all seemed to turn into backhanded compliments. And while I reckon that more or less reflects my feelings about this movie, a mixture of appreciation and dissatisfaction (and my favorite critical sentence formation is always: “On the one hand this, but on the other that”), I didn’t want to approach “Django Unchained” that way. I wanted to start unambiguously with what I see as the highlights and later segue into discussing the reservations I have about the film in its current form.

And that brings up a caveat I’d like to toss in right up-front: Remember when the theatrical version of a movie was pretty much the finished thing? No more. Tarantino has already announced that he plans to release an “extended cut” of “Django Unchained,” and that he and Harvey Weinstein considered putting out the movie in two parts, like “Kill Bill,” but decided against it. At the New York press junket, Tarantino said:

“I’m going to wait until the film goes around the world, does what it does. And then I’m going to make a decision. I make these scripts that are almost novels. If I had to do this whole thing over again I would have published this as a novel and done this after the fact.”

Of course, you can’t judge any work by all the options that were considered but ultimately not chosen — and virtually every screenplay (Tarantino’s included) has scenes or sections that don’t make it into the final cut, or that aren’t even shot. But I think taking the screenplay into account is particularly important when it comes to “Django Unchained” for several reasons. Tarantino has repeatedly said that he sees his screenplays as “novels” and that they should be considered as works of their own, apart from but in addition to the movies based on them. His screenplays are published separately, alongside the movies made from them, and “Django Unchained” has already being issued in alternate forms, not only as a screenplay available online but as a six-part comic-book, which QT says incorporates the entire script. In the forward, he writes:

So even though things might have changed from the script to the finished movie — I might have dropped chapters or big set pieces — it will all be in the comic. This comic is literally the very first draft of the script. All the material that didn’t make it into the movie will be part of the finished comic book story.

So, before I delve further into this, let me, as a former president used to say, make one thing perfectly clear: A movie is not a script and a script is not a movie. It is not necessarily the goal of any movie to be faithful to the script. And filmmaking, like any creative endeavor, is the product not just of planning but of trial and error, happy accidents, last-minute problem-solving and spontaneous invention.

Also: While filmmakers’ original designs and stated goals can be fascinating and shed some light on the creative process, those things don’t change what’s actually there, in the movies themselves. Many a filmmaker has wound up making a movie that thoroughly undermines its creators’ own proclaimed intentions. I try not to read much of anything — reviews, publicity features, interviews, certainly not scripts — before seeing a movie, so that I can experience it fresh, on its own terms. But if, while watching the picture itself, you feel that, say, a scene or a character feels underdeveloped, or that something feels odd or out of place, you can sometimes dig up some interesting clues about how a movie came to be the way it is.

Take Dr. Schultz’s dental wagon with the big wobbling tooth on top, for instance. That was something devised out of necessity by the late production designer J. Michael Riva after Waltz had an accident and was unable to ride a horse for a few months. Tarantino loved it. As he told Tim Appelo in The Hollywood Reporter: “It changes the character and provides some interesting non-corny levity at the beginning of the movie, right when you need it.”

My first impression was that “Django Unchained” was uncharacteristically sloppy — not at all what I’d expect from a Tarantino movie. When I came home after seeing it I immediately looked up the screenplay (.pdf here), which I was sure would be available online “For Your Consideration” at The Weinstein Company web site. And there it was — complete, as usual, with QT’s hand-scribbled title-page (this time with conventional spelling, unlike “Inglourious Basterds“). There were a number of things I wanted to check — like how much character development had been chopped out (a lot, as it turns out); if the movie had been re-structured (yes, significantly — especially toward the end); and if the use of deliberately ostentatious language such as “ascertain” (in a cliched phrase: “I was simply trying to ascertain…”) by both Christoph Waltz’s and Leonardo DiCaprio‘s characters had been scripted (yes in both cases).

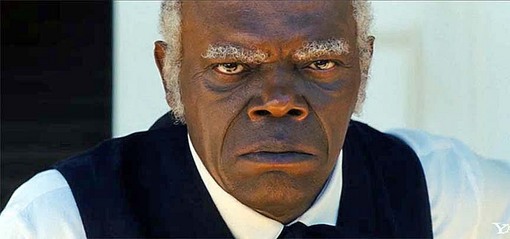

What I learned more or less confirmed what I felt while watching the movie, which reminded of the line Harvey Keitel says to Julia Sweeney in “Pulp Fiction“: “Just because you are a character doesn’t mean that you have character.” This time, there are plenty of characters, but few with much character. Tarantino’s eccentric personalities tend toward the caricaturish and/or archetypal, but they’re usually embellished with colorful, individualized pieces of flair. Few in “Django Unchained” get the opportunity to make much of an impression, with the obvious major exceptions — Dr. King Schultz (Waltz), Django (Jamie Foxx), Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson). It’s not the choppiness of the filmmaking and storytelling that bugs me so much (more about that later), but that the characters are missing a considerable amount of their character.

Jackson and Foxx have said as much in interviews. In fact, their favorite scene together (a charged encounter when Stephen, the House Negro, shows Django, the Freeman, to his room at Candyland) isn’t in the movie. Foxx told The Playlist:

“I still look at Quentin and go like, ‘You should have kept it in the movie. Because me and Sam have this moment of black men — the house servant, the field servant. And how are they going to get along? The house servant who is a manipulative person, and me, the field servant, who just wants to kick ass and kill everybody….

Also: Walton Goggins‘ character Billy Crash was folded into Kevin Costner’s and then Kurt Russell’s Ace Woody after Russell left the movie, and he still doesn’t get to become much more than a generic henchman (although he does memorably take a glowing hot knife to Django’s nutsack). And he’s Walton Goggins, one of my favorite character actors from “Justified” and a spectacular guest appearance in “Sons of Anarchy” (and, I’m told, “The Shield,” which I haven’t seen). Candie appears to have some kind of weird relationship with his Looney Tunes sister, a seemingly brain-damaged Southern Belle named Lara Lee Candie-Fitzwilly (Laura Cayouette), but it isn’t developed into anything. (She’s cartoonishly disposed of — gone with the wind, you might say, though the angle of the shot isn’t quite right.) Other actors in small roles and bit parts are either unrecognizable (by me, anyway), or gone much too quickly: Bruce Dern, Don Stroud, James Russo, James Remar, Russ Tamblyn, Ted Neely, Michael Parks…

At times, the movie seems to run low on imagination or inspiration — as in a long, bloody shootout that’s nothing but long and bloody because you can’t tell and don’t care who the swarms of faceless, gore-gushing expendables are. Two characters are eliminated in almost exactly the same way, shot off their galloping horses from a great distance just as they are about to go out of range. The blood of the first one splatters the plantation cotton bushes; the blood from the second one splashes across the neck of his white horse. The dramatic point might have been that Schultz shoots the first one and Django takes over sniper duties for the second one — except Schultz doesn’t give Django shootin’ lessons until the obligatory montage sequence that comes later, followed by another scope-sight assassination scene. (The latter, in which a man is picked off while plowing a field with his young son, just feels recycled, like we’ve seen it a hundred times before. And even though we know the bounty hunters have to retrieve the body, we never get close to the dead man or his family so the killing business remains “clean.” There’s an important dramatic/thematic note to strike here — about Django learning to master his emotions, to stay “in character” and separate his professional role from his personal reactions — but the movie doesn’t reach it. Not here, at least.)

At two hours and 45 minutes, “Django Unchained” is a long movie, and feels even longer. But I suspect it’s one of those pictures that would seem much shorter and faster-moving if certain missing scenes were restored. Although this is by nature a quest movie, a road movie, with a picaresque, episodic structure, the set-pieces (such as they are) don’t build suspense and the overall narrative feels haphazard and dramatically slack — which is really uncharacteristic of the usually energetic and focused Tarantino. The movie really feels unfinished — like a hastily thrown-together work print. (I later learned that, despite eight months of production and 18 weeks of post-production, things came right down to the wire and the first screening at the DGA was delayed two days for last-minute mixing tweaks.)

You may recall that “Inglourious Basterds,” a movie I thoroughly enjoy and admire, retains a few residual scraps of discarded material (like Samuel L. Jackson’s narration), but it’s structured around four lengthy, impeccably constructed suspense set-pieces, each of which has ample time to intensify until the suspense is almost unbearable: the opening interrogation of LaPadite by Col. Landa, culminating in the slaughter of Shosana’s family; Shosana’s coffee and strudel with Frederick, Goebbels and Landa; the basement tavern scene with Bridget von Hammersmark and Lt. Hickox; and the apocalyptic revenge climax at the cinema.

(spoilers)

“Django Unchained” has one pretty good suspense standoff in a saloon near the beginning and never tops it — or even comes close to it. That’s Schultz and Django’s first stop, and they easily find and take their quarry at the next one — and re-use basically the same trick to escape from a tight spot that’s never that tight to begin with. The climactic suspense piece s a dinner-table scene which consists of conversation about “mandingo fighters,” a barbaric fictional bloodsport named after the 1975 exploitation film starring Ken Norton, a favorite of Tarantino’s. There’s a brutal and horrific death-match that, preposterously, takes place in front of an upstairs fireplace at Candie’s brothel.

When it comes up that Django’s wife (Kerry Washington) is named Brünnhilde (only she’s not, because she’s “Broomhilda” — apparently, for reasons unknown, after a newspaper comic strip that started in the 1970s), Schultz tells Django the Norse legend of Brünnhilde und Siegfried. Waltz/Schultz is such a splendid storyteller that I wondered how Tarantino had matched the story to the actor/character. Later, I found out. Waltz was planning to take QT to an LA production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, but Quentin missed the first opera (“Das Rheingold”). As Tarantino told Taylor Hackford:

Before we went to the second opera, he took me out to dinner and told me the story of the first opera. I’d seen the Fritz Lang “Die Niebelungen.” I was fairly familiar with the legend, but there was nothing like Christoph telling you the story of Siegfried and Brunhilde, he was born to do that, he was terrific, there’s no way the opera will be as good. While I was watching the second opera, I realized the stories were parallel. She’s already named Broomhilda, a coincidence. As I was watching the story I’m realizing how similar it was actually, when I was breaking it down to the story told in the movie.

So, in the second half of the film, the goal becomes finding Broomhilda (which turns out to be really easy to do, what with slave sales records and all), who turns out to be at the aforementioned Candyland. Django comes to see himself as Siegfried, rescuing his beloved. Sadly, Boomhilda’s own story has been all but eliminated from the theatrical release, so she isn’t much of a character. Just when you think we might finally see some interaction between her and Django, she drops in a dead faint. End of scene.

The movie features two racist, paternalistic plantation owners (is that redundant?) — Don Johnson’s Big Daddy DiCaprio’s Calvin Candie (I wish he were Col. Candie, seeing as how he presides over a property inspired by QT’s board-game fetish, Candyland).* Unfortunately for us, there isn’t much to distinguish one from the other, apart from their appearance. Both men are temper-prone Southern “gentlemen” who can be persuaded, for the right price, to offer Schultz a slave girl for his private delectation. But Johnson’s character barely gets a chance to register (except for his final scene on horseback, where we barely even see him).

It seemed to me that there were two big scenes that really didn’t work, tonally and structurally — and it turns out that both were huge chunks that had been moved from one place to another in the film. The first is the bag-mask scene, which plays like an outtake from Mel Brooks’ “Blazing Saddles” (yes, there has been a western about racism before!). The scene, which QT calls his “fuck you” to the KKK heroics in D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation,” also recalls the Robert’s Rules of Order adopted by the People’s Front of Judea in “Monty Python's Life of Brian.” Anyway, it’s the funniest scene but it’s risky because the jarringly different tone can throw the movie out of whack. And something’s off, because the raid starts, we see clearly that it’s all been staged (Schultz and Django are supposedly “sleeping” under the wagon, apparently don’t hear a thing when surrounded by raiders on horseback). The bag-heads unaccountably retreat nearby for no good reason, have their comedy scene, and then resume their raid, which turns out exactly the way we already knew it would. (Again: Poorly conceived set-up, devoid of suspense — not Tarantinian by a long shot!) [NOTE: See comments below. Did I miss something?]

Later, I read QT’s explanation — which acknowledges the challenge, although I don’t think the movie adequately tackles it:

In the script they had the whole bag scene before the charge. I had a trepidation about doing the bag scene. I thought it was one of the funniest scenes in the script, but it played so funny on the page that I was positive I’d fuck it up, it was too funny. I did it, felt ok about it, was scared about editing it. “Lets do the charge first, get our feet wet.” So we did the charge, so fun to shoot, it was my “fuck you” to D.W. Griifith. So I did that, and they’re actually scary, if I show that they’re fucking idiots right at the beginning, I’m going to kick the whole sequence in the shins, right now. So I thought I’d get away by going back in time, and you’d figure it out. I wasn’t sure if it worked, we had a research screening, and we showed it. “Are we going to keep it in?” And everyone laughed more than they did throughout the film, and it’s everyone’s favorite scene. I guess we’re going to keep it in.

A bigger problem is that the climax has been chopped into two anti-climaxes — the first a giant-sized bloody blow-out and the second a half-hearted, by-the-numbers “showdown.” Again, in the script it’s all one scene. The dining room scene begins with a tense kitchen encounter between Stephen and Broomhilda before the meal, which properly sets up their escalating confrontations over the course of dinner. The deal-signing between Candie and Schultz is suspenseful, as each man tries to conclude it on his own terms. But when everything erupts into protracted chaos, the movie just bleeds out. The shooting goes on and on and on, and the Candyland manse is well and truly shot up (only to be miraculously restored a few scenes later). But with one major character dead at the beginning of the gunfight and another at the end, Django is the only one we have any emotional investment in. (At least Jamie Foxx looks ultra-cool — but not, god forbid, “Kool and the gang” — in his Eastwoodian hat, round sunglasses and suave green jacket.)

Tarantino movies have a reputation for being “violent,” but as the filmmaker has been saying ever since “Reservoir Dogs,” his movies are basically “gabfests” in which the worst violence is more often implied than shown. Until now. As he’s pointed out in numerous interviews, what really happened to slaves in America is a thousand times worse than anything in the movie. And “Django Unchained” isn’t so much violent (most of the shooting has little impact; this isn’t Sam Peckinpah visceral violence, it’s more like a Tom Savini special effects show). The aforementioned gun battle is disappointing because it’s so obviously a display of firepower, meat geysers and blood gushers designed to substitute for drama.

Then there’s the torture scene and a conversation between Django and Stephen that carries little weight because (thanks to the missing confrontation scene) there’s not much of a personal dimension to their relationship. Django is sent away, but then comes back to retrieve Broomhilda, anti-anti-anti-climactically gun down the remaining Candyland clan as they return home from massah’s funeral, blow up the impeccably restored Big House, and do a little dance on his horse with Broomhilda leading the applause. The moment feels to me misjudged and unearned. (And, yes, in the script the dinner scene ended with Schultz’s death and the big shootout happened at the end of the movie, during which the characters who matter were also gunned down.)

I always try to remember, when watching a Quentin Tarantino movie, that he likes to make movies he would like to see. That is, he makes movies that are mostly about other movies he’s seen combined with things that have made him go, “I’d like to see that in a movie!” Which is why just about every scene reminds you of some other movie, sometimes with a Tarantinian twist. How much you enjoy a Tarantino movie, then, may have something to do with how much you like the kinds of movies that he likes.

QT says his favorite movie is Sergio Leone‘s 1966 “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” and “Django Unchained” is commonly described by fans and detractors alike as a “Spaghetti Western about slavery.” But I think that makes the movie sound heavier than it is, or is meant to be. This is basically just an old-fashioned, blood-and-gutsy revenge picture (like all of Tarantino’s movies since “Pulp Fiction” “Jackie Brown“) — a juvenile showpiece in both the positive (cheeky) and negative (puerile) senses of the word. It features some of the things I love about Tarantino movies (off-the-wall-crazy choices, like a horseback montage set to Jim Croce’s 1973 “I Got a Name” that’s so anachronistically unexpected — unlike the obligatory James-Brown-“Payback“-sample rap track — that it made me laugh), and some of the things I don’t (the over-reliance on cutesy, cliched and possibly anachronistic figures of speech: “Yes siree bob,” “no muss, no fuss,” “your goose was cooked,” “the price of tea in China,” “I like,” “tasty refreshment” [see Jules’ awkward “tasty beverage” Letterman line from “Pulp Fiction”], “right as rain” [intentionally misused?], “adult supervision is required,” “pleasure doing business with you,” “confidentially, ‘tween us girls” [said by Candie to Schultz], and so on).

In the New York Times, Tarantino said: “I still love “Death Proof.” It is the lesser of my movies though, and I don’t ever want to make anything lesser than that.” But “Death Proof,” simple as it was, was lean and tautly constructed, with momentum, suspense, thrills, energy to burn. “Django Unchained,” I think, is more, but less.

P.S. One more obligatory comment about Spike Lee tweeting that he’s not going to see “Django Unchained”: “American Slavery Was Not A Sergio Leone Spaghetti Western. It Was A Holocaust. My Ancestors Are Slaves. Stolen From Africa. I Will Honor Them.” OK, nobody’s forcing anybody to see the movie and if that’s the way you feel, then you sure won’t want to see this one. I can respect that. But personally, I think that it’s possible to make any kind of movie about anything — which doesn’t mean I’d rush right out to see an action movie about carpeting, but anything’s possible.

But c’mon: We already know this has been presented as a cartoonish, cathartic revenge epic (possibly the second, after “Inglourious Basterds,” in a trilogy of historical revenge fantasies — see some possibilities here). The tongue-in-cheek tagline is: “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Vengeance.” It’s as much about slavery as “Duck, You Sucker” was about the Mexican Revolution.

As for the “daring” idea (“Could a black director have made ‘Django’?“) of showing a persecuted black action-hero taking revenge on Whitey: Anybody ever seen “Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song”? It came out in 1971. It was written and directed by an American black man named Melvin van Peebles.

_ _ _ _ _

* When our bounty hunters cross from Tennessee into the Deep South, the title MISSISSIPPI fills the screen in white capital letters and a Western typeface, scrolling from right to left. Tarantino describes it in the script as appearing across the screen one letter at a time “(ala ‘Rocky’ and ‘Flashdance’)” — which made me chuckle because it speaks to QT’s obsessive affection for 1970s and 1980s pop culture. There’s another, older movie about slavery in the American South, I think it was from 1939…. What was it called?

ADDENDUM (01/04/13):

• Samuel L. Jackson on the unnecessary multiple endings of Spielberg’s “Lincoln“:

“I don’t understand why it didn’t just end when Lincoln is walking down the hall and the butler gives him his hat. Why did I need to see him dying on the bed? I have no idea what Spielberg was trying to do…. I didn’t need the assassination at all. Unless he’s going to show Lincoln getting his brains blown out. And even then, why am I watching it? The movie had a better ending 10 minutes before.”

I kind of felt the similarly.

• Odie and Boone (that would be Odie Henderson and Steven Boone at Big Media Vandalism) loved “Django.” Literally.

Odie:

“Django Unchained” isn’t my dream scenario’s epic statement, but it is the loud noise atop the snow-covered mountain, the sound that will hopefully cause the avalanche. You asked for my falling-in-love moment, and I’ve many to choose from, but I’ll go with QT’s placement of Jim Croce’s I Got A Name. It’s both blatantly obvious and surprisingly touching. Django is surprised King Schultz would allow him to pick out his clothing (“and you chose THAT?” asks the slave girl giving Django the tour of Big Daddy’s Bennett Manor estate), and put him atop a horse of his own. Croce’s lyrics resonate in ways I hadn’t given thought to despite my familiarity with the song. As subtly as Tarantino can muster, he presents the gift of humanity to a former piece of property. I daresay I was profoundly moved.

That’s the polite Negro in me speaking; the hoodrat would go with the moment Django opens fire on the Brittle brothers. “SHOOT THOSE F–KERS!” I heard my inner voice yell. You can take this boy out of Blaxploitaion, but you can’t take the Blaxploitation out of this boy.

Boone:

This movie won’t leave me alone because I, too, fell in love with it. The first swoon was during the scene where King and Django have a teachable moment over beers in a saloon while waiting for a Sheriff to come arrest them. That sequence is the essence of what a lot of Tarantino detractors deny exists: his restraint. The hilarity of that series of negotiations and killings is all about rhythm, pace and QT’s delight in his stylized characters. It’s also the first scene to establish Schultz’s M.O. of exploiting his own whiteness to the fullest. He uses his race and refinement like a CIA asset whose swarthy complexion and command of Arabic lets him move freely through the Muslim and Arab world. The fact that Schultz’s ruse ultimately serves to turn a slave into an avenging outlaw is fucking thrilling to my black eyes.

The second swoon was the entire sequence at Big Daddy’s plantation, Bennett Manor aka Miscegeny Heaven. This is just one of the funniest, most exciting pieces of film I have ever seen. If I had to be a cotton-pickin slave, I’d prefer Don Johnson’s farm over DiCaprio’s Candieland, since it most resembles the world we live in, where folks can live pretty harmoniously so long as there’s ample distraction from routine cruelty and injustice. From Hal Ashby to Aaron MacGruder, I can’t think of too many exchanges of comic dialogue between races as mercilessly true as the one between Big Daddy and Bettina about how to treat Django. Oh, the many times in my life I have been treated “like Jerry.”

JE: I thought the build-up was a little clumsy (Bettina’s attitude should have been more naive, unassuming), but the “Like Jerry” punchline was one of my favorite moments, too.