Dialogue drives Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction,” dialogue of such high quality it deserves comparison with other masters of spare, hard-boiled prose, from Raymond Chandler to Elmore Leonard. Like them, QT finds a way to make the words humorous without ever seeming to ask for a laugh. Like them, he combines utilitarian prose with flights of rough poetry and wicked fancy.

Consider a little scene not often mentioned in discussions of the film. The prizefighter Butch (Bruce Willis) has just killed a man in the ring. He returns to the motel room occupied by his girlfriend Fabienne (Maria de Medeiros). She says she’s been looking in the mirror and she wants a pot belly. “You have one,” he says, snuggling closer. “If I had one,” she says, “I would wear a T-shirt two sizes too small, to accentuate it.” A little later she observes, “It’s unfortunate what we find pleasing to the touch and pleasing to the eye are seldom the same.”

This is wonderful dialogue (I have only sampled it). It is about something. The dialogue comes at a moment of desperation for Butch. He agreed to throw the fight, then secretly bet heavily on himself, and won. He will make a lot of money, but only if he escapes the vengeance of Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames) and his hit-men Jules and Vincent (Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta). In a lesser movie, the dialogue in this scene would have been entirely plot-driven; Butch would have explained to Fabienne what he, she and we already knew. Instead, Tarantino uses an apparently irrelevant conversation to quickly establish her personality and their relationship. His dialogue is always load-bearing.

It is Tarantino’s strategy in all of his films to have the characters speak at right angles to the action, or depart on flights of fancy. Remember the famous opening conversation between Jules and Vincent, who are on their way to a violent reprisal against some college kids who have offended Wallace and appropriated his famous briefcase. They talk about the drug laws in Amsterdam, what Quarter Pounders are called in Paris, and the degree of sexual intimacy implied by a foot massage. Finally Jules says “let’s get in character,” and they enter an apartment.

Tarantino’s dialogue is not simply whimsical. There is a method behind it. The discussion of why Quarter Pounders are called “Royales” in Paris is reprised, a few minutes later, in a tense exchange between Jules and one of the kids (Frank Whaley). And the story of how Marsellus had a man thrown out of a fourth-floor window for giving his wife a foot massage turns out to be a set-up: Tarantino is preparing the dramatic ground for a scene in which Vincent takes Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) out on a date, on his bosses’ orders. When Mia accidentally overdoses, Vincent races her to his drug dealer Lance (Eric Stoltz), who brings her back to life with a shot of adrenaline into the heart.

And that scene also begins with dialogue that seems like fun, while it’s also laying more groundwork. We meet Lance’s girlfriend Jody (Rosanna Arquette), who is pierced in every possible place and talks about her piercing fetish. Tarantino is setting up his payoff. When the needle goes into the heart, you’d expect that to be one of the most gruesome moments in the movie, but audiences, curiously, always laugh. In a shot-by-shot analysis at the University of Virginia, we found out why. QT never actually shows the needle entering the chest. He cuts away to a reaction shot in which everyone hovering over the victim springs back simultaneously as Mia leaps back to life. And then Jody says it was “trippy” and we understand that, as a piercer, she has seen the ultimate piercing. The body language and the punchline take a grotesque scene and turn it into dark but genuine comedy. It’s all in the dialogue and the editing. Also, of course, in the underlying desperation, set up by thoughts of what Marsellus might do to Vincent, since killing Mrs. Wallace is much worse than massaging her foot.

The movie’s circular, self-referential structure is famous; the restaurant hold-up with Pumpkin and Honey Bunny (Tim Roth and Amanda Plummer) begins and ends the film, and other story lines weave in and out of strict chronology. But there is a chronology in the dialogue, in the sense that what is said before invariably sets up or enriches what comes after. The dialogue is proof that Tarantino had the time-juggling in mind from the very beginning, because there’s never a glitch; the scenes do not follow in chronological order, but the dialogue always knows exactly where it falls in the movie.

I mentioned the way the needle-to-the-heart scene is redeemed by laughter. That’s also the case with the scene where the hit-men inadvertently kill a passenger in their car. The car’s interior is covered with blood, and The Wolf (Harvey Keitel) is called to handle the situation; we remember much more blood than we actually see, which is why the scene doesn’t stop the movie dead in its tracks. Scenes of gore are deflected into scenes of the Wolf’s professionalism, which is funny because it is so matter-of-fact. The movies does contain scenes of sudden, brutal violence, as when Jules and Vincent open fire in the apartment, or when Butch goes “medieval” (Marsellus’ unforgettable word choise) on the leather guys. But Tarantino uses long shots, surprise, cutaways and the context of the dialogue to make the movie seem less violent than it has any right to.

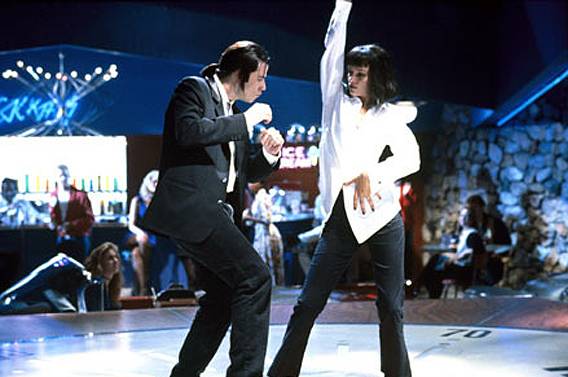

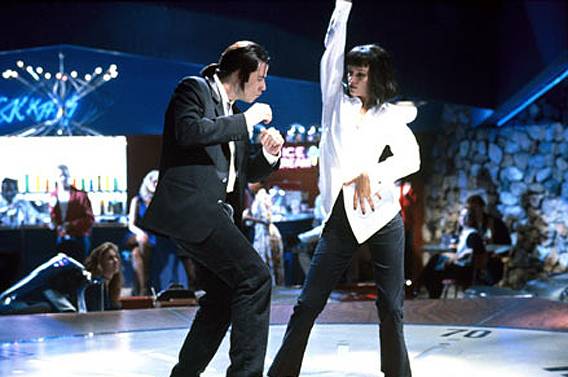

Howard Hawks once gave his definition of a good movie: “Three good scenes. No bad scenes.” Few movies in recent years have had more good scenes than “Pulp Fiction.” Some are almost musical comedy, as when Vincent and Mia dance at Jackrabbit Slim’s. Some are stunning in their suddenness, as when Butch returns to his apartment and surprises Vincent. Some are all verbal style, as in Marsellus Wallace’s dialogue with Butch, or when Capt. Koons (Christopher Walken) delivers a monologue to the “little man” about his father’s watch.

And some seem deliberately planned to provoke discussion: What is in the briefcase? Why are there glowing flashes of light during the early shooting in the apartment? Is Jackson quoting the Bible correctly? Some scenes depend entirely on behavior (The Wolf’s no-nonsense cleanup detail). Many of the scenes have an additional level of interest because the characters fear reprisals (Bruce fears Wallace, Vincent fears Wallace, Jimmie the drug dealer wants the dead body removed before his wife comes home).

I saw “Pulp Fiction” for the first time at the Cannes Film Festival in 1994; it went on to win the Palme d’Or, and to dominate the national conversation about film for at least the next 12 months. It is the most influential film of the decade; its circular timeline can be sensed in films as different as “The Usual Suspects,” “Zero Effect” and “Memento,” not that they copied it, but that they were aware of the pleasures of toying with chronology.

But it isn’t the structure that makes “Pulp Fiction” a great film. Its greatness comes from its marriage of vividly original characters with a series of vivid and half-fanciful events and from the dialogue. The dialogue is the foundation of everything else.

Watching many movies, I realize that all of the dialogue is entirely devoted to explaining or furthering the plot, and no joy is taken in the style of language and idiom for its own sake. There is not a single line in “Pearl Harbor” you would want to quote with anything but derision. Most conversations in most movies are deadly boring, which is why directors with no gift for dialogue depend so heavily on action and special effects. The characters in “Pulp Fiction” are always talking, and always interesting, funny, scary or audacious. This movie would work as an audio book. Imagine having to listen to “The Mummy Returns.”