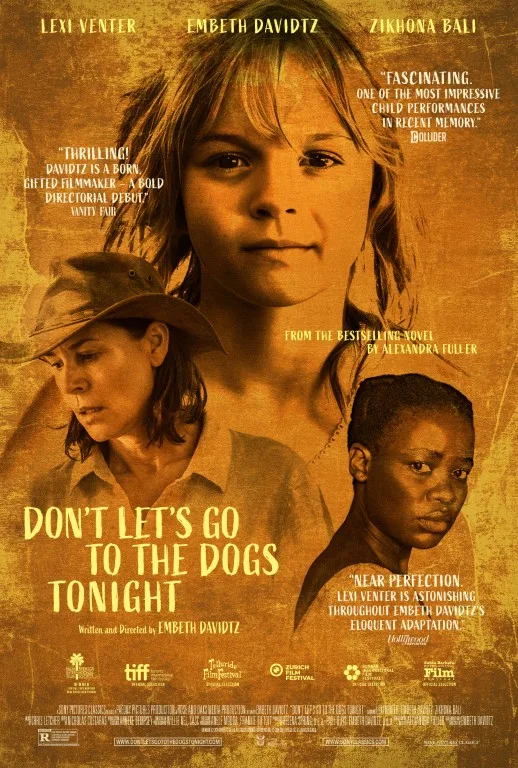

The Zimbabwe War of Independence is raging on in “Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight.” The film is an adaptation of Alexandra Fuller’s memoir of the same name, telling the story of Rhodesia’s (now Zimbabwe’s) civil war in which two nationalist groups sought to overthrow the minority British colonial rule over the country and restore power to native Africans. Embeth Davidtz’s film lands close to home as a South African woman, and the dexterity of her storytelling is certainly due to her proximity to similar dynamics.

“Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight” follows eight-year-old Bobo (Lexi Venter) and her life with her family on their farm. Yet their countryside existence is anything but romanticized. The family’s matriarch, policewoman Nicola (director Embeth Davidtz), sleeps with a rifle in her arms, held with the comfort and delicacy of a child’s teddy. Her hair-trigger tension is constantly held in her rigid body, gaping eyes, and tight timbre of her voice. Paranoia and strain are the marked qualities of her motherhood, which is not tender but stressed and constantly on guard. The family’s father is a soldier, often away on tours of duty, and Bobo’s sister Van (Anina Reed) is often a stereotypically annoyed elder sister. However, she gets a shred of her own peripheral storyline through the predation of a local man.

But Bobo is the center of this story, told through her perspective (and often her direct narration), where the war is presented on the platter of childhood innocence, ignorance, and wonder. Bobo is a bit of a wild thing, riding her motorbike, smoking cigarettes, and getting up to tomboyish mischief, to the annoyance and disdain of both her mother and sister. But she is close with a local woman, Sarah (Zikhona Bali), who provides a level of tenderness, guidance, and even discipline that is absent in her upbringing.

The land itself is a character of the film, tackling both honor and horror. We know that the war was a bush war, guerrilla-fought in the vegetation of the nation. We also know that Bobo cherishes the same vegetation as the only home she’s known, even though it does not belong to her. In a moment that just about sums up Bobo’s innocence and the racism that fueled her mother’s ire towards the war, Nicola tells Bobo that she is not African. When she asks if it’s because her skin isn’t Black, her mother says no, “it’s complicated.”

As adults watching the film, it is easy to pinpoint the racist dynamics that stress the country, and even closer, the community, including Sarah’s husband, who is on high alert about associating with the Fullers. But in this film, they run through the background as context, as our protagonist does not fully understand them. What lies in the forefront is how children see things: often not at all until it is blatant, violent.

On the whole, the film takes place mostly on the family’s farm and the surrounding village. We know it is not a sanctuary, but in a way, it functions as one for the Fullers, even in the tension and paranoia that mar it. This is a war film without battlegrounds. It’s on the outskirts, and it’s this that allows the maintenance of innocence. Bobo is naive. When she plays with the local boys, they roleplay as her servants until Sarah teaches her to see them as children of their own. At a party, with adults swaying, twirling, and laughing above raucous music, her eyes veer to the television, where an African soldier’s head has been partially shot off, and the flicker in her eyes constitutes a new knowing.

“Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight” is inherently bound by its white perspective, but at the same time, it would simply be a different story if not through Bobo’s eyes. Ultimately, it seems content in telling the story it desires. It’s a coming-of-age film that’s more about Bobo’s understanding of race than her own. It is difficult to witness the operations of a racist family’s clutch on their stolen land, and the film, in part, pardons itself on the basis of Bobo’s primary perspective. Though in the end, as Bobo imagines Sarah through her mind’s eye, “Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight” still seems aware, with a hint of biting realism, that a prototypical perspective is maintained; Bobo still has a lot to learn.