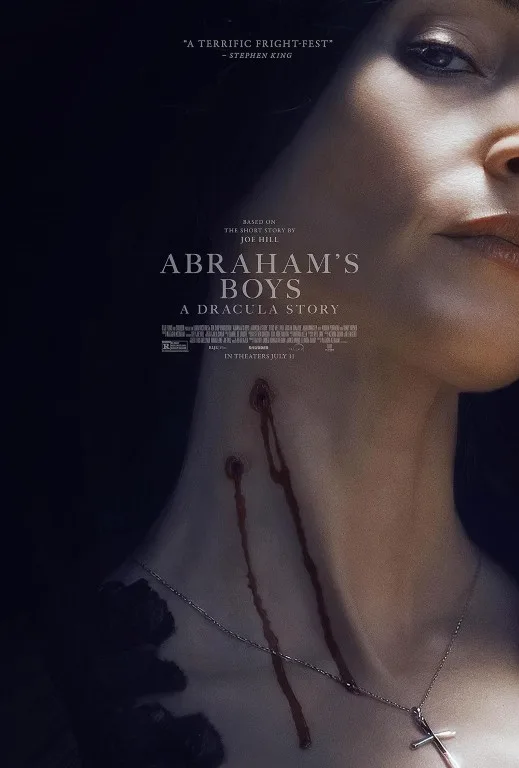

It’s no secret who Abraham is in “Abraham’s Boys,” a short horror story from Joe Hill that’s been adapted into a feature-length gothic psychodrama by writer/director Natasha Kermani (“Lucky”). Hill uses one of his title characters’ full names, Max Van Helsing, in an establishing paragraph. Maybe that’s (one reason) why the title of Hill’s story received a clarifying extension for Kermani’s thoughtful, but bloodless chiller: “A Dracula Story.” Suggesting that Kermani’s version is one tale among many also takes some pressure off of her loose and intriguing take on Hill’s plot, which differs in at least one major way—Kermani’s boys still have a mother.

Hill’s story focuses more on the suspicious adolescent Max (Brady Hepner) and his impressionable younger brother, Rudy (Judah Mackey), as they struggle to understand their domineering and mysterious father, Abraham (Titus Welliver). The boys’ mother, Mina (Jocelin Donahue), remains a part of their past. “She died when I was six,” Max tells his brother when Rudy asks if Mom ever actually said that vampires attacked her. Kermani lets Mina speak for herself, having survived London and moved to America with her new husband, Abraham. That’s a theoretically interesting extra twist that Kermani sadly doesn’t take far enough.

To be fair, “Abraham’s Boys: A Dracula Story” offers viewers a refreshingly clear understanding of who its characters are and why they act like they do. Kermani’s Mina suffers from perfunctory visions of the past, which, admittedly, serve their purpose in a movie with that fully loaded title. Mina also understandably worries not only Max, but also Kermani’s secretive and overbearing Abraham, played with an appropriately starchy reserve by character actor champ Welliver.

Does Max’s father really know what’s best for his mother? It’s hard to say for a while, though the answer seems plain, especially given some early dialogue exchanges, like when Mina says to herself that she would have preferred to have a daughter. If she had, her child might have been “softer” and also “more difficult to keep safe.” Max and Rudy must ultimately judge their father, a difficult task for them that, unfortunately, is too easy for viewers, given how dramatically sparse and visually flat Kermani’s movie tends to be.

There’s nothing wrong with Kermani’s take on Bram Stoker’s characters, though it does strongly bring to mind the superior “Frailty,” Bill Paxton’s eerie 2001 horror drama about two boys and their crazed father. Kermani’s dialogue spells out a lot of what makes her characters distinctly hers, like when Mina insists, “He moved like a ghost…the others never saw him. I did. I remember. Your father saved me.” Too bad so much time and dialogue are wasted on constantly setting up incidents and developments that rarely get developed to an appreciable point.

It gets hard, after a while, to watch Kermani’s protagonists explain away the wisps of drama that trail after them. Welliver and Donahue also lack chemistry, which makes it harder to care when they exchange lines like, “I’ll never leave you,” and “I don’t believe you.” That retort should sting, but it doesn’t even have the hammy character of Abraham’s non-apology to his kids after he inevitably smacks one of them: “I suppose I have never raised my hand to you before. Mother has made me gentle.”

It’s also hard to appreciate a Dracula story that doesn’t nail Abraham’s wobbly stab at introducing his sons to the family business. It’s a key moment in Hill’s version, too, but is notably less unsettling in Kermani’s story. Ditto for a later (and new to the plot) scene where a character from Abraham’s past appears unexpectedly and asks him point blank: “What if we made a mistake?” That’s a good question, but it feels tacked on at the end of this re-tailored story.

Kermani deserves credit for expanding on Hill’s story, which has a great premise, but not much else going for it. At least this movie takes time to listen to the wind, as well as the soft crunch of gravel beneath the characters’ feet. The rest is as airless and underdeveloped as its source material, which is now stretched thinner to accommodate a raft of superficial developments. It might have been nice, for example, if either Mina or Max had a deeper connection with Elsie (Aurora Perrineau), a new supporting character who drifts in and out of Kermani’s story without adding much.

Then again, Abraham’s barely a strong enough presence in this movie, though his influence supposedly haunts both Mina and her children. A few standout images and well-timed looks from Welliver suggest a darker, more engrossing film. There’s also a suggestive and well-timed moment at the end of the movie where Abraham suggests that he’s a product of his own father’s parenting. If only the rest of the movie were so affecting.