I owe a good part of my sensibility, if not my career, to the films of Mark Rappaport, an American director who now lives in Paris. A complete archive of his work has just become available on Fandor.com, including three new pieces, and I highly recommend checking them out. Since there’s a good chance many of the people reading this won’t be intimately familiar with everything he’s done, I’m going to talk about his two best known works in this introduction, and get to some of the others in the course of a conversation I had with him last week via phone.

I first encountered Rappaport’s work over twenty years ago, when his films “Rock Hudson‘s Home Movies” and “From the Journals of Jean Seberg” were being shown theatrically in New York. Both are hybrids of biography and criticism, produced without copyright clearance. Employing a number of scenes from an array of films, some of which play out uninterrupted, they push the Fair Use exemptions of intellectual property law to their breaking point. Rappaport’s unswerving belief that this was public material and that he was quoting from it, annotating and transforming it, and therefore needed no one’s permission to use the material, guaranteed that the films could only be screened in nonprofit venues.

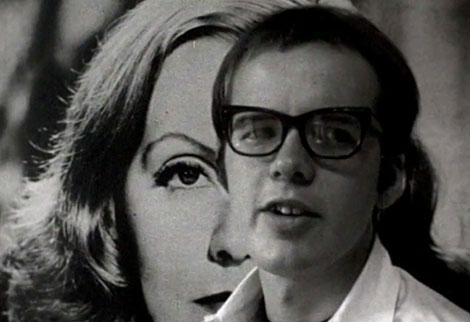

The movies take us through the lives of their title characters by way of performances (by Mary Beth Hurt as Seberg and Eric Farr as Hudson), but without trying to convince us that these actors have “become” their real-life characters. Instead, “Hudson” and “Seberg” become conduits for Rappaport’s observations about the films, the actors’ lives, the relationship between the two, and our perceptions of what certain films “mean” based on what we know about the actors.

Over and above their considerable merits as both pure cinema and works of film education, these movies revealed to me that it was possible to keep a film buff or even a general audience member interested merely by juxtaposing scenes or sections of a pre-existing movie with narration that talks mainly about the movie, or the movie in relation to a particular subject, such as Hudson’s status as a closeted gay man in pre-Stonewall Hollywood, or Seberg’s involvement with left-wing political causes. This approach differs pretty drastically from most documentaries about films, filmmakers and film stars, where the focus is on the life, and the film clips serve as mile markers on the journey: “Oh, here we are in 1966, when Rock Hudson starred in ‘Seconds,’ I wonder who he’s dating at this point?” The emphasis instead is on the work, first and foremost, and the associations the work sparks in the critic or filmmaker, in this case Rappaport. Most interpretive or academic video essays take this sort of approach, though of course not many of them employ professional actors to articulate the filmmaker’s observations.

I talked to Rappaport about these films, plus his newest works. One is “Max and James and Danielle,” a piece about the film director Max Ophuls and the actors James Mason and Danielle Darrieux, who each were each in several Ophuls projects but acted together in one of his films. Another is “Debra Paget,” about the actress who costarred with Elvis Presley in “Love Me Tender” and became a star of sorts in gladiator and swords-and-sandals films. A third is “I, Dalio,” about Marcel Dalio, the French actor who is perhaps best known for his small role in “Casablanca,” as a croupier who says, “Your winnings, sir,” after Claude Rains’ police captain declares that he is shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in Rick’s establishment. When the Nazis rolled into Paris, Dalio’s face was used in propaganda as the face of a stereotypical Jew. Rappaport considers this in relation to his roles before and after the German occupation.

We talked about his projects, mostly, but there are detours into the changing technology of filmmaking, which made the production and distribution of Rappaport’s kind of movie easier. And we also talked about video essays themselves: what they’re good for, what kinds he likes and doesn’t like, and some ideas for works that he would very much like to see.—Matt Zoller Seitz

When you read pieces by people like me calling you “the father of the modern video essay,” what do you think? Do you say, “What the hell are these people talking about?”

Um, no. I think I know what they’re talking about. It makes me feel very old indeed, but no, I kind of get it, because in some sense, these sorts of films are the kind of thing that [Jean-Luc] Godard, 24 years ago, pointed the way toward, with new technology that was not available to me.

Are you talking about “Rock Hudson’s Home Movies” now, specifically, or a different one of your films?

“Rock Hudson’s Home Movies” and “From the Journals of Jean Seberg,” both. The new technologies have made that way of thinking more possible. I’m very glad that I’ve lived to partake in all of these technologies, because before the VHS player, you were kind of at the mercy of your memory and repertory theaters. VHS and subsequently DVDs and Blu-rays and Internet has made [my] kind of reconsideration of our recent past possible, and that’s very gratifying that this stuff can be made, and can be made available very quickly.

When I made “Rock Hudson’s Home Movies,” I had to transfer it to film in order to have it seen, period. And it was very expensive, making the transfer from video to a 16 mm film, and then you had to mail out the prints [to theaters]! Of course now, with the Internet all this stuff is right there, it’s like one-stop shopping. You do it, you click on it, it’s out there, so this is quite amazing.

My parents were a lot older than most people’s parents, and I always wondered how they made the transition from horses to automobiles, from nothing to radio and then to televise, and I feel that I’ve been living on a similar time of the transition technologically, going from TV to means of reproduction where you could have all this stuff in your house—that is to say, your favorite movies on VHS and then DVD, and now at your fingertips, on your two-way wristwatch.

[laughs] Dick Tracy!

Yeah, Dick Tracy, exactly! This is what he was talking about all these years: the two-way wristwatch! We never knew it before, but now we do.

But yes, it’s an interesting transition period, and I feel very lucky, because although it’s a very fallow period for films, but it’s a time for a very serious reconsideration of the past. All of these technologies permit that.

Speaking of reconsideration of the past, I’ve just watched—I had never seen it before—your short film, “Mark Rappaport: The TV Spin-Off.” That’s from 1978. It starts out with you—I guess you’re just physically leafing through stills—and talking about these images in close-up. And then you start talking about your movies, and it hit me all of a sudden that this is basically the narrated video essay as it is practiced today, except we’re ripping DVDs with HandBrake and ripping them in Adobe or Final Cut Pro or something like that. But you’re just a guy moving pictures around with his hands and talking, and I guess either you or someone else is triggering the music that plays in the background behind you, right?

Yeah.

Is what you were doing in 1978 a more basic approach to the same kind of idea?

Yeah, yeah! Well, I think I’ve always been very limited, I guess we all are—we see things from one perspective and basically we live our lives from that one particular perspective, but I think I was talking to somebody fairly recently. I said, “I re-saw the first movie I had ever made, and everything in that movie is there, and I will draw on it for the future, and things that I made today relate to that movie.” You know, like people against a background of a huge still. And I was just shocked when I realized that, because it was almost fifty years ago that I made that!

One is always a prisoner of one’s own life, in a sense. But that’s a good sense.

If had wished for something 20 years ago, I would have wished for Final Cut Pro, but I am not a visionary, and I could want things, but I couldn’t invent them, any more than I could invent VHS or DVDs or the delivery of movies to your home though the Internet.

Could you walk me through your evolution as a filmmaker in regards to your storytelling devices? Specifically, the point at which you decided to use actors to represent stars, such as Rock Hudson and Jean Seberg? They are not speaking dialogue that is supposed to be Rock Hudson or Jean Seberg as we might think of them in a docudrama.

I have no idea! I don’t remember quite at which point I was going to make “Rock Hudson.” It was always going to be a first-person narrative, and obviously that person is dead and wouldn’t, in all likelihood, have the insights into his life and work that I might’ve had. I don’t know, I think when I had to write stuff up for film festivals, I decided on this format called “the fictitious autobiography.”

Yes, I remember you using that phrase when I interviewed you in back in ’95.

Oh really? [laughs] Oh god, how dull of me.

No no! It just stuck in my mind because it’s a great phrase. I was struggling—I had asked you to help me to describe what you were doing in films like “From the Journals of Jean Seberg” and “Rock Hudson’s Home Movies.” I was writing for a pretty wide readership, most of who had probably never seen anything like the work you were doing at that time. When you watch those movies, you are seeing Rock Hudson and Jean Seberg as you might see them in a biography, but at the same time, they are saying things that those people would never say because Rock Hudson and Jean Seberg don’t have the knowledge of a film historian or a critic.

That’s right. They couldn’t have an overview of their careers before they died.

I was saying “fictitious biography” even back then, when you first interviewed me, because I had written something for film festival catalogues, and they want to know what the artist’s intent is.

They never ask real filmmakers about this, they only ask experimental types. “Tell me what it means, the author’s intent.” Has anyone ever asked Stanley Kubrick, “What does it mean?” I don’t think so.

[laughs] No, probably not.

They would be afraid of getting bitten in half, anyway. “What does the bone turning into the spaceship mean?” I give up. Shrug of shoulders.

Stephen King once said—he was in a particularly grousey mood—something along the lines of, “I’m so sick of people asking me where I get my ideas. The next time someone asks me that, I’m going to tell them that I subscribe to a magazine called, ‘Ideas.’”

[laughs] Yeah, well I get my ideas while watching movies. It’s very relaxing and very stressful at the same time. Gives me a lot of space to think. The worse the movie, the more I think.

Interesting. So during bad movies your mind wanders and you come up with ideas or solve problems?

Yeah. I don’t pluck daises and sniff them. I’m writing reviews at the same time. The first time I saw “Mystery Science Theater 3000,” I said, “Oh my god, this is my life story.” You’re sitting there practically screaming out at the screen, “No no, don’t open that box,” or, “Don’t go in the closet, don’t go in the cellar,” or finishing lines of dialogue before they’re said.

So I think that, in a sense, “Rock Hudson’s Home Movies” and “From the Journals of Jean Seberg” come out of that. I’m yelling back at the screen, but in retrospect.

You’re also at times—or at least it seems to me—you’re entering the movie.

You’re really not altering the dialogue, you’re not altering the lighting, you’re not altering the gestures and the facial expressions of the actors. You are presenting the scene, and all that you are adding is a perspective and a point of view, however jaundiced or far away from the intent of the original makers it may be, but the scene itself, you can’t really argue with it.

Like I was telling you, in most film criticism, certainly before the invention of VHS, everybody would get everything wrong all the time because they couldn’t go back to check it before publication, and one of the real whoppers is Raymond Durgnat describing “Under Capricorn” in his writing, and then Francois Truffaut taking Raymond Durgnat’s description in the “Hitchcock/Truffaut” book and getting everything all wrong. He’s the cousin, not the nephew! He gets everything wrong, and this is in the book. But no critic was able to really verify anything that they said because you saw a movie once, and then you had to wait until next time it came around in repertory theaters or in a 16 mm print in your class. So this is not lying in the sense that I’m presenting a scene that already exists, of course I’m lying a little bit in the angles that I’m approaching it from.

Right, you mean in the sense of having Rock Hudson or Jean Seberg say the things you have them saying?

Well, sure, yeah.

Yeah. It’s fascinating to me too how you are almost forming a bridge between the audience and the movie. When you make these movies, you’re not entirely with the audience, but you’re not entirely of the movie. It’s like you become this third thing somewhere between them, if that makes any sense at all.

Yeah—a vacuum cleaner and a pinball machine in “Mystery Science Theater 3000.”

Can you tell me a little about “Exterior Night”?

Prior to “Exterior Night,” my first Adventure in Videos—that gets capital A, capital V—was “Postcards,” and I loved the idea of these—now I can’t even remember the English word—these chromakey green screen/blue screen “fakeology.” You could insert a person into whatever background you wanted to, and when I made “Postcards” in 1989-90, this technology was just coming into being, although they’ve used it in newscasts all the time. The anchor person is sitting in the studio and behind him or her, there is a blizzard in New York on the screen, but when I first used it, they had eliminated that horrible little green line or little blue line around them. If you’ve seen “African Queen” recently, you can see those green lines screaming at you.

Like the scene where they’re going down the rapids?

Yeah, and I loved the fakery of it, the compacting different spaces and different possibilities, and the French word for that sort of thing is much more interesting than “chromakey” or “keying in.” To me, it’s like putting some jewels in some gold ornament and just heaping tons and tons of jewels on them.

I wanted to do another version of “Postcards” using actors in deep space, and a friend of mine, Pierce Rafferty, who had made “The Atomic Cafe” with his partners—his brother and Jayne Loader—had just gotten the Warner Bros. library from 1931 to 1951. They had gotten all of the rear screen projection plates from Warner Bros. These were the things that they would project to suggest a street at night because they had only shot in the studio and you never went outside the studio, or they’re driving through the desert. Nobody actually drove through the desert—not the actors, anyway. You had the car and you had the rear screen projecting the road behind them. So Pierce had everything from Warner Bros. from 1931 through 1951 and he made this stuff available to me, the only condition was I had to have the negative clips transferred to video and then I could use them, but I would have to give the videos back to him, which enabled him to show them to prospective buyers. Subsequently it was sold to Getty or Corbis or something.

So essentially you were making your filmic art from these old rear projection plates, and then the guy who let you use them got a show reel out of it!

Yeah, but on top of that, I had written a script, and I had written it very, very quickly, and then I had to find backgrounds to fill it in. It’s a very interesting and very crazy-ass backwards process, but I love that kind of problem solving, doing things that are really not possible, but finding them possible overall. I love the artificiality of it, the condensing of live flesh space with space that has been dead for 40 years, and making it into one new thing.

It’s the kind of stuff that I’m still doing.

And the thing is, as well as you know, some of the movies that I’ve borrowed [rear projection] clips from, you will never be able to find them in the [actual] movie they were made for. Somebody had suggested at the time, “Why don’t you identify the movies you got these things from?” I said, “’Nobody really cares. I care, you care, but they don’t care.’” Well, there are a lot of things they don’t care about—but that’s certainly one of them.

You’ve been working in this mode—it’s very elastic—but you’ve been working in this mode for 20 years, a little more …

I’m not sure what “this mode” means because I think that I’m in a different mode now from when I was making those films. I think the videos that I’m doing now are somewhat similar but they’re different. In a sense, they’re so much easier and faster but can be much more complicated than what I did twenty some odd years ago, and I think the pot is really boiling now. Then it was like very hesitant baby steps, but now it’s like, “Okay, I’ve finished one, now give me the next one,” and I love that feeling, the feeling of, “Okay it’s April, I’m going to finish three more by the end of August.”

So there is something very fresh about them because, in a sense, this is not even bragging, when I start taking extracts, I really have no idea what I’m going to say. I really don’t. I say, “Okay, I think I can use this, this I can’t use this other thing,” and I may be wrong. I may find out three years after I’ve finished the film that “Oh, my God, I should have used that other part of the movie!”

But when I think that I can use something, usually I’m right. And then I start writing and narrating at the same time.

I don’t write anything beforehand. Well, that’s not true of “Jean Seberg,” I wrote a lot beforehand. But I find the thing on the editing table, and it’s very exhilarating when [I find] “that shot should go with that shot.” It opens up this whole new chest of treasures. “Oh gee, I didn’t even know that went with that.” It’s a very improvisatory way of working, and I like that way of working a lot, and I don’t know what I’m going to say in advance, and it’s great. I kind of discover the material as I go along, and it’s exciting.

Do you follow many video essay makers now? Are you familiar with the work that’s being done out there, to any degree?

Every time I start watching them, I start exploding a little, so I have to kind of stay away from it. It’s like, “Why are you describing exactly what’s being shown on the screen? We see that it’s a man walking down a corridor. Why are you saying, ‘And then he goes down a corridor’? We know this already.” So I don’t do very well with that, although some of them are interesting and some of them should be made, and I want to give the overflow to other people, but nobody’s listening, so … [laughs]

I think there are some video essays that are dying to be made by feminists, and nobody is picking up the slack here. Well maybe somebody is, maybe somebody out there in the dark, as Norma Desmond used to say, “All those wonderful people out there in the dark waiting for my return to the screen.”

Give me an example of a topic you’d like to see somebody do a video essay about.

Women in westerns—first of all, I’ve always hated westerns, so I should preface it with that, until I discovered Anthony Mann, and then I kind of got into some westerns—every western has women being pursued and/or almost raped. They are rarely actually raped, of course, but rape must’ve been such a f—king everyday part of every life in that great mythic West that everyone seems to idealize! In every Gary Cooper western, if he’s around, the women are not going to get raped. In “Vera Cruz” or “The Hanging Tree” or “They Came to Cordura,” he is always preventing the women from getting raped. But what happens when Gary Cooper is not around?

Recently I saw “Day of the Outlaw” by André De Toth, which is a great movie, and all of the guys, the hoodlums, all they want to do is rape the women. That’s the first thing they want to do when they come to town, and somebody could make a great video essay about demythologizing the great American western, the way it’s always treated women—Joan of Arc or civilizing influences. The Tommy Lee Jones movie, “The Homesman” was the only movie I’ve ever seen which suggests that all is not really that great for women on the western front. Having children that died or going crazy or being raped or can’t stand the hardship—send them back home to the east, where they’ll fit in just fine. [laughs]

There have been a few other westerns along those lines, but they generally have not been ones that mass audiences turned out to see.

Well they didn’t turn out to see “The Homesman,” either!

The thing that you’re describing is what I guess people now call a supercut, where they’re assembling different examples of one particular thing.

When I saw that in relation to my name, I googled “supercut.” [laughs] I did, I am not exaggerating. So I learned what supercut means!

The supercut has been corrupted. I’ve talked about this with my friend, Kevin B. Lee. It has been corrupted by a lot of commercial media outlets, where it’s like every time somebody farts in a particular sitcom or things like that.

But, I’ve found that it can be very illuminating when you string together things like you just mentioned. I have long wanted to do a video essay about the normalization of torture in American movies as practiced by characters who are police officers and military people.

That’s great.

Every time there’s someone who has a piece of information that they won’t give up, the hero slaps them, threatens to send them to prison where they will be anally raped, dangles them out of a window ledge or a balcony, and then they always give up the information, and it’s always correct information. They never give them the wrong information and they never make up a lie so the cop will stop torturing them, and I have to wonder if 30, 40, 50 years of seeing this kind of scene in movies and on TV—

Has led us into waterboarding.

Exactly!

America, land of the free, home of the brave! There are millions of examples of this—you’re walking down the street innocently and a cop comes along and looks at you funny, and people start cringing. What is the cop doing in the dance number in “Singin’ in the Rain”? They are always intimidating.

It is a fascist country. You could string forty of those moments you describe together, and that’s not even ones that have black people and cops with night sticks. That’s just your friendly Irish cop on the beat.

Yeah, I think there is a lot to do in this area, and there is a lot that can be done.

I think a lot of people making videos take an easy way out because it’s just so much easier to make video essays now than when I was first doing them.

But, I especially loved when “Brokeback Mountain” came out and all those revisionist versions of the “Brokeback Mountain” trailer with “Back to the Future”…

I think that the one with “Heat” was also pretty good, and doing all those different things with “Downfall,” I thought that was brilliant, really hilarious. “Downfall” still has a lot of juice left in it.

It’s interesting, this thing we’re talking about, because in many of your movies, it seems as if you have been looking at—I hate to be using the word ‘messages’ because it sounds so stentorian, so maybe the worldview that’s being articulated by movies. It seems to me that you don’t make films about movies that you entirely dislike. These tend to be movies that you have complicated relationships with.

Between the time I left the United States ten and a half years ago and, let’s say, 2008, I did a lot of writing, and I could write about stuff that I didn’t like, and you would never know it’s in the content of the piece, but things that were good springboards for me or good jumping-off points to get into something else were always very useful, so liking or not liking a movie is, to me, almost irrelevant.

If I really love something, it’s much harder to deal with it than if I feel kind of neutral about it. I don’t think I could ever do anything about Hitchcock or—well that’s not entirely true—or Ophüls or Visconti. It would just be too hard, and I don’t think I could. I just couldn’t.

Stuff that I feel more neutrally about is much easier to work with.

I never get the impression that you’re saying these are great are unambiguously healthy movies. It’s not “two thumbs up, go see it.” It’s more about examining the work than recommending it or telling people it’s bad and they shouldn’t see it. I feel like you’re torn, and I say “you” loosely, because it’s obviously not Rock Hudson but a quote-unquote “Rock Hudson” who is doing the talking for you.

I don’t know, it’s very easy being the medium for a dead person somehow! I don’t know why, but it is. [laughs]

It’s very bizarre, because until just very recently, anytime the name Rock Hudson is mentioned, my hand shoots up and I say, “Here! Present!” I don’t do that anymore, or I don’t feel that impulse anymore. I never had any great affinity for Rock Hudson, either before he died or after he died. I never really cared about any of his movies except “Tarnished Angels” and “Written on the Wind” and “Seconds.” Jean Seberg was really very close to my heart, but then you go through all those movies and the closeness kind of evaporates a little. What a dirty, sordid life. Poor woman.

William Inge—God, I would love to do something about William Inge! [laughs] Is “Picnic” not the faggiest play ever written?

[laughs] It is!

Aside from “ A Streetcar Named Desire.”

Calling it coded gives it too much credit.

Right, it’s totally uncoded. It’s as coded as William Holden’s chest in that movie. Walking around having all these women drooling—really, the men in the back row were drooling even more!

American films are really a treasure chest of articulated desires, repression, violence, and they know not what they’re talking about, or at least the movies then didn’t know. Maybe the movies now know what they’re talking about, I’m not sure.

American movies from any era are just begging to be psychoanalyzed. But earlier ones seem richer to me, because they’re not out there trying to psychoanalyze themselves first so that you don’t have to.

Yeah, that’s why I find the ’40s and ’50s so rich. Even if they knew a little bit about themselves, they didn’t know enough.

You know, I thought of another topic for our hypothetical feminist video essayist: “women in jeopardy” is a genre that starts in the earliest years of movies and continues all the way through “Alien” and beyond. I’d love to see a piece that’s about the history of the woman-in-jeopardy movie.

There is so much there, there is so much work to be done, and here we are, wasting time talking on the phone!

We should talk about my recent work!

Could we talk about “The Circle Closes” and “Max and James and Danielle”? We’ve talked about video essays as they’re practiced now, but these two new ones feel very much like a more recent iteration of what your’e doing. This is not “Rock Hudson’s Home Movies.” It feels different to me, in intent and style.

I think it’s another branch. It’s trying to elucidate practices in filmmaking and following ideas in a different direction rather than structuring them int terms of a personality or a career. I think they’re more freeform—certainly “Max and James and Danielle” is more freeform. I wouldn’t even call that one an essay. Clips lead me from one idea to another to another to another.

These were made as a result of having spent so much time on longer pieces. I wanted to do some stuff that was shorter and faster, and get stuff off my chest much quicker. But of course they all wind up taking more time than you think they should! I’m doing a few in that kind of vein right now. I think it’s refreshing to be able to do shorter essays where you kind of follow your instincts on them, and it takes you to a place where you didn’t even know you were gonna be going.

What was the impetus for “Max and James and Danielle,” which is pretty wide ranging to be such a short piece?

Well, it’s about Max Ophüls and James Mason and Danielle Darrieux, I like the idea of putting things that might not normally go together, go together. I like that way of working. It’s a playful way of tromping through film history in a short piece, with the understanding that these films will have a limited audience. You have to be interested in that sort of thing to be interested in that sort of thing. Basically I’m talking to myself.

You are musing, and I see you following your own train of thought. At one point you even have a sort of parenthetical aside about Max Ophüls and Stanley Kubrick and their use of the dolly shot!

Well, it’s on record that Kubrick’s use of the dolly was strongly influenced by Ophüls, and here’s proof positive—showing clips of two moments from a film by each of them, where the camera is placed below eye level, moving through rooms that don’t have walls. The positioning of the camera is almost exactly the same in relation to the actors. The similarity couldn’t be clearer. And there’s no reason for me to say any of those things, because the evidence is right there onscreen. I don’t want to be a schoolmarm about it, because this is not film appreciation class.

But of course, there is that part of me, too!

Your short piece “The Circle Closes” is a very graceful example of the kind of free-associative, pattern oriented filmmaking that you’ve talked about here. It’s a little anthology film in itself. You follow the trajectory of four filmic objects—the earrings from “The Earrings of Madame De,” the donkey in “Au Hasard Balthazar,” the rifle in “Winchester ’73,” and the jump rope from “Viridiana“—as they move through their respective stories, and build a kind of philosophical framework around them.

This was something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. What prompted it was accessibility of being able to do it on Final Cut. I have been writing a lot, from about 2000 through 2008, and I kind of stopped writing, not because I don’t like it, but because I’d run out of things to say. I found that making films about the subjects was a more direct, graphic, accurate way to describe the things I wanted to talk about.

In “The Circle Closes,” I can only hope to kiss the hems of the robes of the people who made the films. I am a worshipful acolyte. I am only pointing out things that might not have occurred to other people as they’re watching the films, and maybe suggesting connections between the films that you may have felt but never articulated as fully as you might have. I’m there as a facilitator.

The best compliment I ever received was somebody saying that after he saw “The Circle Closes,” the part of the film that deals with “The Earrings of Madame De” made him run out and get the DVD of the film and watch it.