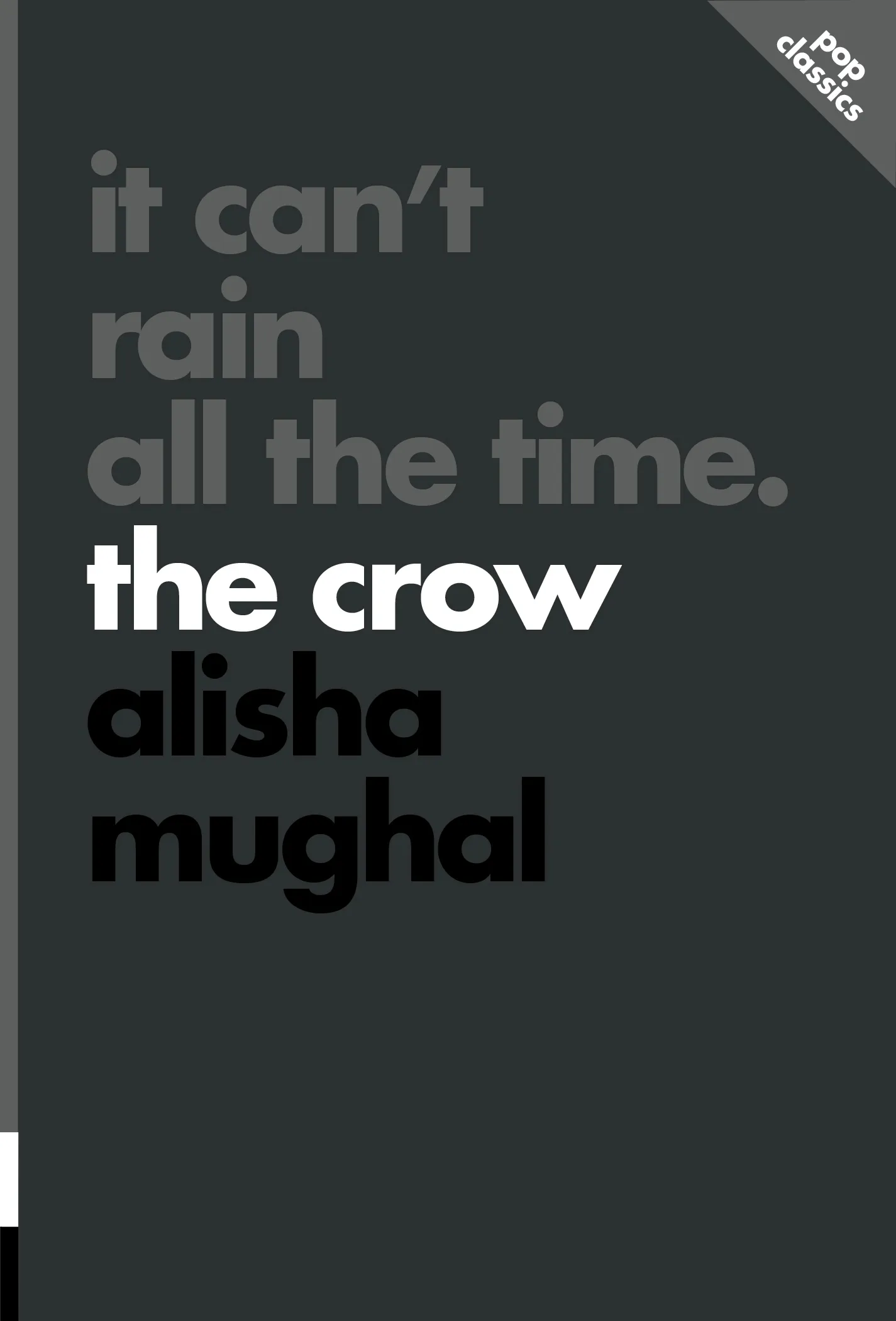

We are extremely proud to present an excerpt from a new book about “The Crow,” available today. Alisha Mughal, who has written pieces for us about “Fatal Attraction,” “Picnic at Hanging Rock,” and more, has written It Can’t Rain All the Time. Get a copy here.

The official synopsis:

It Can’t Rain All the Time weaves memoir with film criticism in an effort to pin down The Crow’s cultural resonance.

A passionate analysis of the ill-fated 1994 film starring the late Brandon Lee and its long-lasting influence on action movies, cinematic grief, and emotional masculinity

Released in 1994, The Crow first drew in audiences thanks to the well-publicized tragedy that loomed over the film: lead actor Brandon Lee had died on set due to a mishandled prop gun. But it soon became clear that The Crow was more than just an accumulation of its tragic parts. The celebrated critic Roger Ebert wrote that Lee’s performance was “more of a screen achievement than any of the films of his father, Bruce Lee.”

In It Can’t Rain All the Time, Alisha Mughal argues that The Crow has transcended Brandon Lee’s death by exposing the most challenging human emotions in all their dark, dramatic, and visceral glory, so much so that it has spawned three sequels, a remake, and an intense fandom. Eric, our back-from-the-dead, grieving protagonist, shows us that there is no solution to depression or loss, there is only our own internal, messy work. By the end of the movie, we realize that Eric has presented us with a vast range of emotions and that masculinity doesn’t need to be hard and impenetrable.

Through her memories of seeking solace in the film during her own grieving period, Alisha brilliantly shows that, for all its gothic sadness, The Crow is, surprisingly and touchingly, a movie about redemption and hope.

A depressive episode begins as a slow and steady sinking feeling, like being lowered inch by inch into a grave. I feel it build over the course of a couple of days or sometimes even a week. I grow irritable, and my moods begin to turn putrid as negative thoughts lay roots. As my body grows tired, the thoughts become a forest. The episode has set in.

When I was younger, I was consumed by the muck of sadness, and many times, I almost didn’t make it out. Now I’m on medication, which doesn’t completely stop the episodes but does allow me a remove, a distance from which I can make decisions to help myself. I’ve learned that the only thing I can do is to let these episodes play out, allow them to peak and then fade and then, eventually, recede. This takes time. Sometimes I watch movies as the hours pass.

The first time I watch The Crow is during a depressive episode at the beginning of the summer I turn 29. Scrolling through the horror streaming platform Shudder, I see the film’s poster image one empty evening. It’s still light out, and I hear sounds that never fail to make me feel like the loneliest person in the world: people laughing, children playing. I vaguely recall the film’s association with some kind of catastrophe, which I learned about from online critic Marya E. Gates years ago. In the state that I’m in in my darkening bedroom — my eyes sore and my mouth feeling like it’s stuffed with cotton balls — I can’t recall much else about the film.

As I’m staring numbly at the screen, my sleepy attention is piqued by the poster’s suffocating darkness stained with the red gash of a title: it’s a heavy black relieved only by the lead actor’s name and a steely gray-white light, like a doorway just opened onto something magnificent. “Believe in angels,” the film’s tagline, framed in the light, advises. On the threshold, a small and menacing figure is visible as if in relief, his arms hang as a sentence cut short, flexed at his sides, making him look like a panther about to pounce — he is as dark as the velvety black on the poster’s body. He is walking toward the viewer, perennially. It is a moody image, sinister and gothic, and, on this empty evening, it complements my melancholic insides, so I press play.

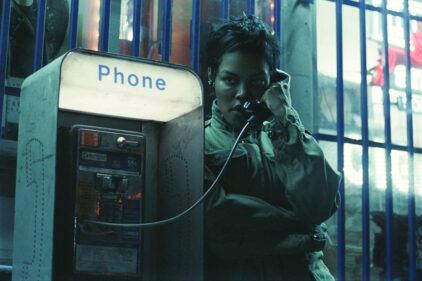

A horror overcomes me. I see Brandon Lee’s Eric Draven lying dead on the street after being thrown from his apartment window and then crawling his way out of a muddy grave moments later, screaming and wailing from the pain of a macabre rebirth. When I hear Eric speak for the first time in the movie — he whispers his cat’s name, Gabriel — his voice low and gravelly from the strain of life so recently shocked into him, I turn the film off and weep. I can’t finish it. Not yet.

Lee’s stature, his voice, his rain-sodden hair — it all reminds me of a person I am trying very hard to forget. “It hurts to watch because you look so much like him,” I say when I manage to see him a few weeks later, the first time in a year. The Boy I Was Trying to Forget isn’t exactly the direct cause of my sadness. It’s my own unreciprocated and unbearably heavy feelings for him that leave me feeling unmoored, which then feed into the loneliness that characterizes my depressive episodes. Everything becomes so dire, so tangled, because of and within my mind.

It might seem anticlimactic or boring or unimportant, maybe even anti-feminist, to say that my fascination with The Crow was first sparked by a man who didn’t like me back. But it’s the truth.

Later that summer, it finally dawns on me that he, the person whose loss I ought to be able to deal with, would never change his mind about me. And it is only at this point, when I understand that my hope will not be enough, that I will have to deal with the finality of his indifference to me — that I sit myself down and watch The Crow in its entirety.

And then I watch it again, and again, and again. Every night that I am sad and weeping, every night that I feel as lonely and meaningless as a lace handkerchief lost at sea (so much elaborate intricacy, so much feeling, all wasted), I put it on. The first time I visit one of my dearest friends in San Francisco, I talk her into watching it with me. It is her first time. We suck gin gimlets through puckered lips, and I become teary-eyed watching Eric Draven twirl and charge and weep and wail.

Now two years have gone by, and I’ve come to realize that I turned to The Crow so often that first summer because it was a way to avoid reality, a way to avoid countenancing and mourning and moving on from the end of a connection. The film allowed me closeness with a person who was far away and would never come near. He wasn’t dead, but this was worse, I once thought with self-pitying conviction. When a loved one dies, you at least have the assurance that there had been love. But this, of course, was a false comparison; it is objectively not preferable to lose someone to death. Still, that certainty I once felt was deeply, pleasingly maudlin, a kind of gothic romanticism. Just like everything I love about The Crow.

Directed by Alex Proyas, The Crow is based on a graphic novel of the same name by James O’Barr. It was released in 1994 after a fraught production period beleaguered by time constraints, delays, and mishaps. Hurricanes tumbled through the miniature city Proyas had built, crew members suffered accidents, and, most notably, lead actor Brandon Lee died on set due to a misfired, misloaded, and mishandled prop gun. During filming, in the face of so many accidents, many on set thought the film was cursed.1 It was well-received by critics, with nearly everyone noting the irony of a lead actor dying during production for a film about a character brought back from the dead. Roger Ebert stated that Lee’s performance is “more of a screen achievement than any of the films of his father, Bruce Lee.”2 The critical consensus on Rotten Tomatoes is that the film is “filled with style and dark, lurid energy,” and that it carries “a soul in the performance of the late Brandon Lee.”3

It made a lot of money, was considered a sleeper hit at the box office, and spawned three standalone sequels that are, honestly, very terrible. Today, the film has a devoted cult following. At screenings, some fans dress up as Eric Draven, painting their faces black and white and caping their bodies in a glossy black flowing trench coat. Sometimes, they adhere a prop crow to their shoulder in honor of the talismanic animal that serves as a shepherd and guide and spiritual conduit for Eric’s soul. There are some critics, though, who wonder whether this movie would still have a devoted following were it not for the real-life tragedy.

The first time I saw the film in a theater, some audience members laughed during scenes that, to me, were never very funny. At one point, Eric, after arming himself with all manner of weapons at a pawn shop (where he also recovers his dead fiancée’s ring), picks up an electric guitar. The unplugged guitar moans: its strings, as Eric carries it away, vibrate, creating a ghostly boing-oing-oing. Watching the film with an audience, I could see how that scene, the juxtaposition of guns with a guitar, could seem a bit funny — a man arming himself ahead of battle takes only the most important things. Surely a guitar is a bit too extravagant? But at the same time, I wanted to shush everyone. Couldn’t they see that the guitar is important to Eric, a musician, just as much as the ring? To laugh is to misunderstand Eric, for whom nothing is trivial or extravagant, and everything is significant. People laughed nonetheless, and at other moments, too, when things became a bit clunky and ludicrous.

“Very bizarre situations are often darkly funny,” said supporting cast member David Patrick Kelly in a behind-the-scenes interview for The Crow,4 reinforcing that the wry humor was purposeful and necessary. The film was pieced together under traumatic circumstances, and this sometimes comedic overwrought-ness is central to its ethos. The Crow is all about a romantic and melancholic pain like an exposed nerve, which the film prods and pokes with the same macabre curiosity that prompts us to press on a tender bruise and can also make us laugh in discomfort or dismay.

In The Crow, there is a pain that is too much; it throbs and glistens with lifeblood, even in and around so much death, appearing on characters in ways that rail against logic’s expectations. The curious thing is that, although this heavy darkness is easy to slip into when sad, it’s not an easy watch precisely for this heft. The film’s pain ricochets through me during every one of my rewatches, reawakening and corralling to the surface all my own fanged memories, which can be, in a sort of paradox, a celebration of life. Pain is messy, emotions are gooey, and they bleed into one another. But ultimately, and most importantly, tears, fear, laughter, and grief are signs that we are alive, a truth that The Crow is a brave and relentless reminder of.

1 “The Crow,” IMDb, accessed May 3, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0109506/trivia/?item=tr2585918&ref_=ext_shr_lnk.

2 Roger Ebert, “Reviews: The Crow,” movie review and film summary, RogerEbert.com, May 13, 1994, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-crow-1994.

3 “The Crow,” Rotten Tomatoes, accessed May 3, 2024, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/the_crow.

4 “Behind the Scenes «The Crow» (1994),” YouTube, January 27, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hmaimTyH56g.

Excerpted in part from It Can’t Rain All the Time by Alisha Mughal. Copyright © by Alisha Mughal, 2025. Published by ECW Press Ltd. www.ecwpress.com