For this series, MZS starts writing on a chosen film and stops 30 minutes later. On a film turning 50 this year…

Robert Altman’s “Nashville” is a portrait of the United States on the eve of the Bicentennial, but at times it seems to be describing the United States fifty years later. I saw it on a big screen during its fiftieth anniversary re-release and was knocked out again by its audacity and perceptiveness.

As is the case with most Altman films, “Nashville” is an ensemble piece, boasting about two dozen recurring characters, and nearly as many bit players floating through. The opening credits sequence mimics TV ads for compilation albums that were popular at the time, with an announcer shouting each performer’s name as their face appears onscreen. The introductory section cuts between musical performances in two studios: jingoistic country-western star Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson) performing a Bicentennial themed song that leans heavily on his family’s military record, and white gospel singer Linnea Reese (Lily Tomlin) recording a song with the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, a historically Black university. These two characters are among the film’s many indelible creations and stand alone as individuals. But they also communicate the cultural divide separating factions that had been battling for control of the United States since the Civil War, and that are still fighting today. One is reactionary, looking nostalgically backwards at times that never existed. The other is progressive, looking forward to a truly egalitarian democracy that didn’t quite exist then, and seems more remote now than it did in 1975.

The movie takes its time introducing all of the other characters and organizing them around a Bicentennial-themed concert that is to be headlined by Barbara Jean (Ronnee Blakely), who is making her triumphant return to performing after surviving what was described to the public as a burn accident but was really a nervous breakdown. Jeff Goldblum has one of his earliest attention-getting roles as a seemingly mute hippie who rides into town on a gigantic motorbike and is introduced doing magic tricks at a counter in a diner. Keith Carradine plays arguably the most successful musician of the bunch, a singer-songwriter and Casanova who beds several female characters in the cast and lies by omission to convince them that his catchy love song “I’m Easy” (written and performed by Carradine, and the future winner of a Best Original Song Oscar) is about each of them. Ned Beatty is Delbert Reese, Linnea’s husband, and a political organizer and lawyer. Delbert’s fixation on making everything work out no matter how weird and bad things get makes him seem like a cousin of another great political enabler from movie year 1975, the mayor of Amity in “Jaws.” He doesn’t want to solve problems, he just wants them to magically go away.

Altman worked from a script by regular Altman collaborator Joan Tewkesbury, based on her observations from visiting Nashville as an outsider. In time-honored Altman tradition, these ended up serving as more of a set of suggestions than a closely followed blueprint, though some core elements remain, including a pileup on the freeway that causes a traffic jam. You could make the case that the visiting English radio reporter (Geraldine Chaplin) who superimposes her own preconceived notions onto the city is a lightly satirical nod to how the source material came about.

“Nashville” was shot in and around Nashville in the summer of 1974, more than a year after the last American combat troops were withdrawn from a defeat in Vietnam that tore the country apart politically. This was also the summer that then-President Nixon—whose fascistic beliefs had driven the country to the brink of constitutional crisis—got impeached and decided to resign rather than face conviction and removal. (“If the president does it, that means it is not illegal,” he told interviewer David Frost.)

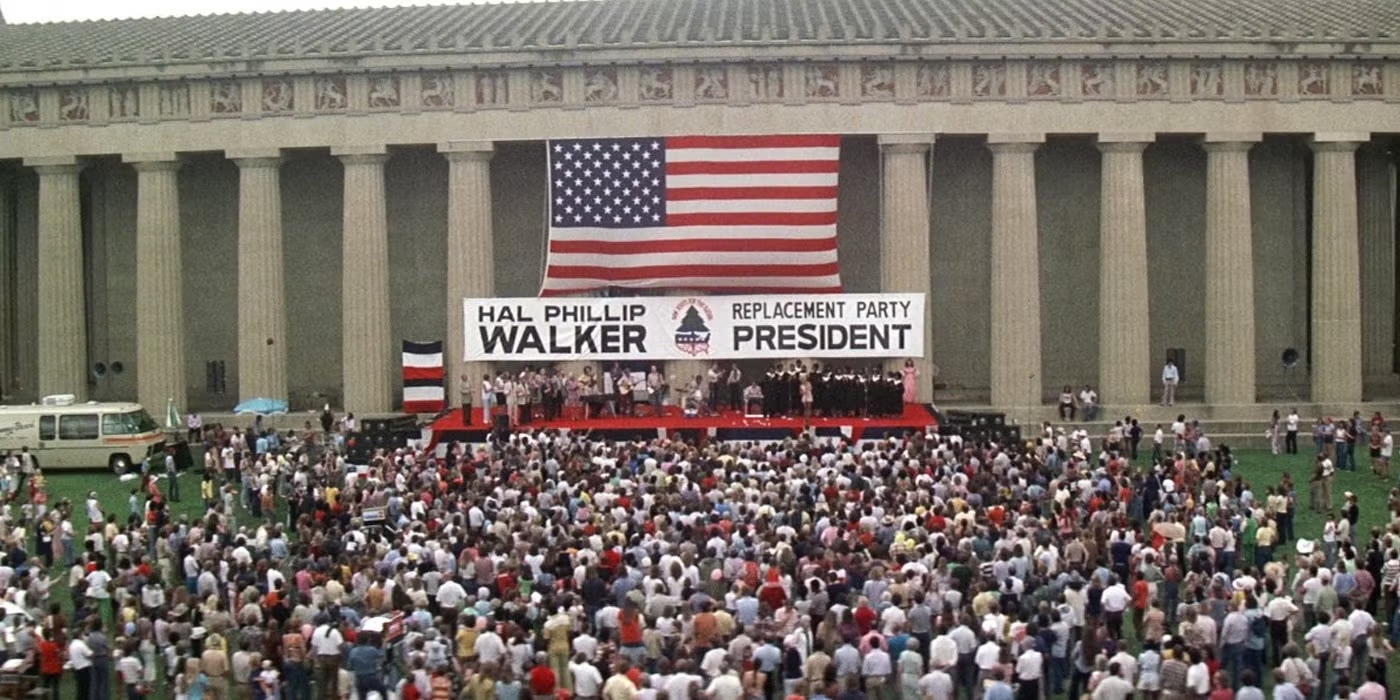

The climax, an enormous concert gathering nearly all of the major characters together, was shot in Centennial Park in Nashville on August 28, twenty days after Nixon quit in disgrace and Gerald Ford, his vice president, replaced him (and controversially pardoned him). We think of the United States circa 2025 as a place that’s violent to the core, with some of the most shocking brutality carried out by agents of the state. But that’s what the late 1960s and early 1970s were like, too, in their way. There were politically motivated bombings and robberies of banks and armored cars; terrorist attacks and airplane hijackings; strikes and protests that escalated into violence through police misconduct; assassinations and attempted assassinations of public officials, and a collective fear that new horrors lurked around each corner.

This took a toll on the body politic. “Nashville” captures this. Numbed exhaustion courses through every frame of the movie, along with its twin, nihilistic hedonism. People are addicted to alcohol, drugs, sex, attention, and maybe worst of all, hope. It’s all a distraction from misery. A publicity team for a third-party presidential candidate drives through the city in a sound truck spouting self-contradicting nonsense. He’s against the Electoral College, the National Anthem, oil companies, and do-nothing lawyers in Congress, but we never hear what he’s for.

Haven Hamilton’s wife Lady Pearl (Barbara Baxley) sums up the malaise that would define the second half of the seventies, and that originated in the bloodshed and dashed dreams of the sixties, when she drifts into a reverie about Democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, one of many representatives of hope who were shot to death during that era. “I worked for him,” she says. “I worked here, I worked all over the country, I worked out in California, out in Stockton. Well, Bobby came here and spoke and he went down to Memphis and then he even went out to Stockton California and spoke off the Santa Fe train at the old Santa Fe depot. Oh, he was a beautiful man. He was not much like John, you know. He was more puny-like. But all the time I was workin’ for him, I was just so scared – inside, you know, just scared.”

The myopia of “Nashville”’s characters is funny and poignant. They’ve been knocked around by life and retreated into themselves—and it appears that the times themselves are partly responsible. The utopian fantasies of the sixties were bludgeoned into submission by retrograde elements of the culture, paving the way for the 1970s, wherein the counterculture’s political fire was extinguished, leaving only lifestyle-based rebellion. It was called The Me Decade for a reason. The politics of resentment are all the characters have, if they want to be political at all. Most don’t, aside from wishing that the world wasn’t so cruel. Barbara Harris’s character Albuquerque, an itinerant singer, warns, “If we don’t live peaceful, there’s gonna be nothin’ left in our graves except Clorox bottles and plastic fly swatters with red dots on ’em.” The closing song, also written by Carradine, is an anthem about giving up and checking out, titled “It Don’t Worry Me.” One of the lyrics is, “You may say/That I ain’t free/But it don’t worry me.” It’s the anthem of the frog in the pot who keeps revising the amount of heat he can endure.

This was my first viewing of Nashville on a properly large screen (all the other times had been on home video or in a classroom) and the scale not only revealed little details I had never noticed but made me realize I was wrong about its point-of-view. The director has a reputation as a cynic or misanthrope. That’s not right. A friend who saw “Nashville” said afterward it was a more compassionate movie than he remembered. I felt the same way.