“What good is it only being pretty?” a 19-year-old girl asks her mother in “Picnic.” “I get tired of only being looked at.” To which her mother can only reply, “What a question!” In Kansas of 1955, being a pretty girl was pretty much a lifestyle in itself, and when Marge (Kim Novak) is crowned Queen of Neewollah (that’s Halloween spelled backward), all she can do is clutch the bouquet of roses and promise not to get too conceited.

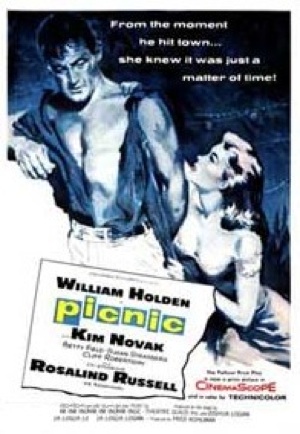

It’s hard to believe that “Picnic” was considered hot stuff in 1955. Clunky and awkward, with inane dialogue, it’s a movie to show how attitudes have changed. It’s easy to see why ’50s audiences responded–William Holden and Kim Novak look great and generate a certain dutiful chemistry–but hard to see how, in a time when the sexual boldness of movies like “A Streetcar Named Desire” was well-known, people could sit through this with a straight face.

The movie, now restored in a handsome new wide-screen print, takes place on a long Labor Day and the night and morning which follow. It begins as Hal Carter (Holden) hops off a freight train and goes looking for his old college roommate Alan (Cliff Robertson). Hal was a football hero, but now he’s a bum and needs a job. Alan takes him up atop one of his family’s grain elevators, and Hal explains what he has in mind: “A nice little office where I can have a sweet little secretary and talk over the telephone about enterprises and things.” He’s promised the job. Meanwhile, he’s fallen into the orbit of the Owens family, who run a boarding house. There’s mom (Betty Field), the beautiful Madge and her kid sister Millie (Susan Strasberg), who sneaks puffs on cigarettes and is college- bound and has read the same page of her Flannery O’Connor novel so often, it’s creased and dog-eared (if we notice things like that, why can’t the prop department?).

Mrs. Owens is pushing her daughter’s romance with Alan, the rich kid from the right side of town. But then Madge lays eyes on Hal, who first appears to the Owens women while burning trash for kindly ole Mrs. Potts next door. Holden, who spends much of the film stripped to the waist and much of the rest with his shirt torn, stands behind the trash can so that the flames wrinkle the air in front of him, and looks like a Chippendale boy on yard duty.

The film’s center section occurs at the Labor Day picnic, where the Halloween queen begins her reign. Director Joshua Logan, among the worst filmmakers of his time, spends so much footage on the picnic, you’d think this was a documentary: There are crying babies, laughing babies, frowning babies, three-legged races, pie-eating competitions, balloon drops, concerts and boy-girl contests.

The Owens gather with several friends, including Rosalind Russell as an old-maid schoolteacher, Arthur O'Connell as her cigar- chomping beau, and Alan, who watches uneasily as sparks fly between Hal and Madge. This scene, like several others involving a lot of characters, is awkwardly composed. All of the actors are lined up from one edge of the Vista.Vision screen to the other, seemingly not noticing that they’re all facing in the same direction (ours).

As night falls, Madge and Hal begin to dance together sensually, in the movie’s famous sexy scene. Madge, dizzy with passion, tells him, and I quote, “You remind me of one of those statues–one of those old Roman gladiators. All he had on was a shield.” Meanwhile, the Rosalind Russell character gets drunk and hysterically demands that her old coot marry her.

The actual subject of “Picnic” is the utter irrelevance of women in that place and that time, unless they were young and pretty and not too smart. Madge says wistfully that she wishes she were as smart as her kid sister and were going to college, but her mom gives her hard-headed advice: Marry the rich kid, quick. (“A girl gets to be 20, 21 and then she’s 40.”) The movie is possibly not aware of two ironies in its examination of the female dilemma. One is that Madge, “tired of only being looked at,” falls instantly for Holden, who only looks at her. When he talks, it is of his own dreams, his own past, his own desires. To hear him explain it, the best thing about Madge is how much he loves her.

The second irony is that the Holden character is treated exactly like the women in the movie. Like them, he’s not considered to be very smart. Like them, he’s physically attractive. Like them, he’s displayed in beefcake poses. He should listen to Mrs. Owens and marry a rich kid himself.

The movie doesn’t have the self-awareness to know that Hal faces the same dilemma as Madge; it’s blinded by the fact that he’s a man. At the end, he hops a freight to Tulsa, where he’ll get a job as a bellboy. Madge rebelliously follows him on the bus (which conveniently stops right in front of her house). When they get together in Tulsa, they’re gonna get mighty tired of only being looked at.