Ebert’s 10 best:

1. “Hoop Dreams“

2. “Pulp Fiction“

3. “GoodFellas“

4. “Fargo“

5. “Three Colors Trilogy”: “Blue,” “White,” and “Red“

6. “Schindler's List“

7. “Breaking the Waves“

8. “Leaving Las Vegas“

9. “Malcolm X“

10. “JFK“

Scorsese’s 10 best:

1. “Horse Thief”

2. “The Thin Red Line“

3. “A Borrowed Life”

4. “Eyes Wide Shut“

5. “Bad Lieutenant“

6. “Breaking the Waves“

7. “Bottle Rocket“

8. “Crash“

9. “Fargo“

10. “Malcolm X” and “Heat” (tie)

Ebert’s Best Film Lists1967 – present

GUEST CRITIC: MARTIN SCORSESE, DIRECTOR

TAPE DATE: 12/99

AIR DATE: 2/26/00

ROGER EBERT (ON CAMERA): Coming up next, filmmaker Martin Scorsese joins me to pick the best films of the 1990s.

ROGER EBERT: “Fargo,” “The Thin Red Line,” “Pulp Fiction.” At the end of the first century of film, one of America’s greatest filmmakers joins me to select the top ten films of the 1990s. I’m Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times. And on this special edition, I’ll be joined by the director whose films “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull” were voted by many groups as the best films of the 1970s and the 1980s.

MARTIN SCORSESE: I’m Martin Scorsese. Hello. And thank you Roger for bringing me back to Chicago and the snow.

ROGER: You know, in the film business we kind of came in together because at my first Chicago film festival, in 1967, I reviewed your first film. And I predicted in that article that you would be a great director, and boy, was I right! And on today’s show, we’re going to review the top four films on our separate lists, and then list our top ten films of the decade. So let’s start with my Number 4 film, which is “Fargo,” from 1996, by Joel and Ethan Coen. And here are two of everyone’s favorite performances from the decade- Frances McDormand as a very pregnant police chief, questioning William H. Macy, as a very nervous car salesman who is up to his neck in a false kidnapping.

CLIP

ROGER: The most remarkable thing about “Fargo” is the way it combines a genuinely exciting and ingenious crime plot with such a good-hearted portrait of a plucky policewoman. And the photography makes the weather into a character, too–that cold white snowy wasteland where cars won’t start and even the cops wear Elmer Fudd hats. “Fargo” — one of the best films of the decade.

MARTIN: I loved the picture, especially the scene you just showed, the wonderful interrogation scene and the wonderful performances by everybody in the picture, Macy and McDormand. And particularly Macy’s kind of passive-aggressive character. I liked the whole picture, because it’s sort of a, it’s a comedy of manners. It’s a movie that once it’s on, if it’s on television I’ll keep watching the whole thing. I get caught up in it. And there’s also that wonderful scene with this Asian-American guy. Everyone else seems to be holding back their emotions and this guy completely disintegrates

ROGER: “I’ll sit over here with you,” and she says

MARTIN: “I think you better sit.”

ROGER: “No I think you better sit back over there.” But then the next morning she calls her friend and she finds out everything that guy told her was a lie and that’s when she decides to go back and talk to Macy again in the scene we just saw —

MARTIN: Exactly. Exactly.

ROGER: — because she realizes maybe this guy was lying too. And that’s her entry into the whole case.

MARTIN: Yeah. And the photography was wonderful. Roger Deakins. Beautiful stuff.

ROGER: Yes it is.

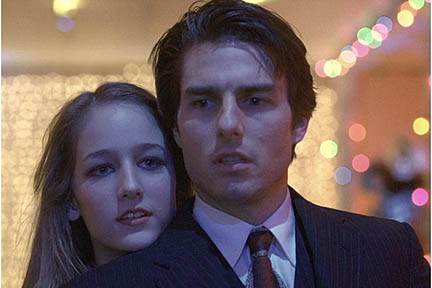

MARTIN: My Number 4 film is “Eyes Wide Shut,” Stanley Kubrick‘s last, which was released in July of 1999 and it stars Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as a happily married couple who realize, thanks to a conversation that begins very casually, just how fragile the bond between them actually is. This sets Cruise’s character off on a real odyssey.

The key stop on his journey is a Long Island mansion, where a bizarre secret ceremony is underway.

CLIP

MARTIN: I think a lot of people were looking at “Eyes Wide Shut” from the wrong angle – it’s not to be taken literally. It’s Manhattan as you’d experience it in a dream, where everything feels familiar but very strange. And I think “Eyes Wide Shut” is a profound film about love, sex, and trust in a marriage, about learning to take things day by day, and either accepting or ignoring whatever unpleasant truths come along. It’s also a film I cherish because it puts you in the authoritative hands of an old master, with a style that flies in the face of every modern convention.

ROGER: It does. And, you know, people put it up to this test of reality as if that means anything.

MARTIN: I know.

ROGER: I got e-mail from people saying, “Well, you could see that there was an English sign in the window of one of the stores,” or “It wasn’t really shot” or “There’s no street in Manhattan that’s that narrow or doesn’t have any traffic.” Of course there isn’t. You know, I’ve got news for them, “Rear Window” wasn’t shot in a real city either.

MARTIN: Exactly. Exactly.

ROGER: The whole point is that you elevate the material with your style into something special. Otherwise just go out and visit New York if that’s what you want to see.

MARTIN: Exactly. Exactly. And there are all kinds of clues in the film as to that in a way, because you really take a journey inside Tom Cruise’s mind in a way. And this wonderful sense of sexuality and guilt and unpleasant discoveries and the journey the marriage has to take, all building up to the last line, which is a beauty.

ROGER: Yes it is. Yeah, it’s a great film.

Segment II

MARTIN: Continuing our special show on the best movies of the ’90s, my choice for Number 3 is a 1994 Taiwanese film called “A Borrowed Life,” directed by Wu Nien-jen. The Chinese title is “Do-sang,” which means “Father.” It’s an autobiographical story about a poor family in the Taiwanese countryside during the 1950s, right after the end of Japanese rule and the nationalist secession from the mainland.

CLIP

MARTIN: The camera remains still, it lives with the characters, and it observes their most difficult emotional interactions with a restraint that often becomes painful. This is a movie that forces you to re-think how you view movies. If you go with it, if it clicks for you, the results are very rewarding.

ROGER: The camera holds back, it doesn’t become a protagonist along with the characters. And here’s the mother —

MARTIN: Yeah.

ROGER: — and here’s the father —

MARTIN: Yeah.

ROGER: — and here’s the kid.

MARTIN: Yeah.

ROGER: It says here they all are and here is this period of time they’re living through and you begin to realize that you’re like another observer there in their house.

MARTIN: Exactly. You become part of the family —

ROGER: Yes.

MARTIN: — whether you like it or not. Because the picture has a lot of domestic violence in it. In fact, in one scene the camera’s inside the house and the husband and wife go outdoors and you hear them fighting outside. The camera stays inside and in a way you don’t want to go out there, but you’re part of the family.

ROGER: It stays inside, like the narrator who was the little boy —

MARTIN: — as a little boy. Yeah.

ROGER: — and he probably stayed inside and he heard his parents fighting and this has made an impression on him.

MARTIN: And it’s a true story. I mean, this writer-director is the writer for Hou Hsiao-hsien’s films “Dust in the Wind” and “The Puppetmaster.” And I think “Dust in the Wind” is the same story from the other point of view.

ROGER: Okay. Now for my Number 3 film, which is named “GoodFellas,” from 1990, by — Martin Scorsese. It’s based on the life of Henry Hill, a mid-level professional criminal who told his story from the safety of the witness protection program. And Henry Hill knows the mob from the inside out, but so I think in a way, do you, Marty. I think this scene that we’re looking at now may be based as much on your childhood as on Henry Hill’s, since you grew up in New York’s Little Italy and observed the local characters at first hand. “GoodFellas” stars Ray Liotta as Hill, and Robert DeNiro and Joe Pesci as two of Henry Hill’s associates in crime, in a world where good-natured kidding can turn in the flash of a moment to sudden violence.

CLIP

ROGER: The visual style of “GoodFellas” subtly keys off the movie styles of the decades it considers, and the rhythm relentlessly builds, until at the end, as Henry Hill senses capture growing closer, we realize we’re breathlessly running right along with him. “GoodFellas” combines wisdom about human nature with a spellbinding story, and it’s one of the best films of the ’90s.

MARTIN: Thank you. I don’t have much crosstalk on this one so…

ROGER: Is it true that you tried to reflect in the various decades of the film the way that the movies from those decades more or less looked?

MARTIN: In a way yeah, particularly, but I really tried to take care of that in the costuming and the set decoration really. That’s the main thing. And music of course.

ROGER: To me the most remarkable thing about the film is the way that without really calling our attention to it you get us all wound up with tension at the end when he realizes that the net is drawing closer.

MARTIN: Yeah.

ROGER: And he’s trying to just go through the daily tasks of an ordinary day —

MARTIN: Yes.

ROGER: — and it’s not.

MARTIN: Well, the whole lifestyle has destroyed him, especially the drug taking. He believes helicopters are chasing him, well they become just as important as the tomato sauce. Now something’s wrong. All the priorities are upside down and that’s I wanted to give the people in the audience who never had a feeling of paranoia like that or the feeling of paranoia whether it was induced by reality or by drugs, I wanted to give them that impression of what it feels like.

ROGER: It’s remarkable that anything can be more important than the tomato sauce.

MARTIN: I would go for the sauce of course, naturally.

Segment III

ROGER: Continuing this special show, Martin Scorsese and I make our personal selections of the best films of the 1990s. And the Number 2 film on my list is possibly the most influential film of the decade, Quentin Tarantino‘s “Pulp Fiction,” from 1994. The movie looped through time to tell parallel stories involving two-bit criminals, broken-down boxers, low-level drug dealers, gangsters’ girlfriends and hit men, in a movie that combined sudden bursts of action with ironic comedy, parody, and characters who loved to make small talk on their way to big moments.

CLIP

ROGER: If you follow the characters through the loop-the-loop of the plot, you also find that most of them do find personal redemption in one way or another so that “Pulp Fiction” becomes a comedy masquerading as hard-boiled. And it’s a complete original, which unfortunately inspired way too many other young filmmakers to write way too much Tarantinian dialog. They knew the words, but not the music.

MARTIN: What I love about the picture is the structure, the way he tells the story, the many different stories and literally the humor, the irony and all based on the bedrock of the American pop culture. Which threw me at first in terms of … at first I approached the picture as a kind of realistic film in a way or naturalist. Not naturalistic, but realistic in the way these people would behave. But who are these people? I’ve never met people like this.

ROGER: You know, Paul Schrader, who has written four of your films, was telling me that he feels in the ’90s that existentialism, the idea of what we do with our lives, has been replaced by irony so that everything has quotation marks around it. Your films are not in quotation marks, they are meant. Do you feel any urge at all to start using the quotation marks or is it just

MARTIN: Oh no. Never.

ROGER: Alien to you as a filmmaker.

MARTIN: No, no I just can’t. I just have to be attracted to the material, really the characters; the morality of the characters is what I’m interested in. And how one deals with morality in today’s world.

ROGER: And “Pulp Fiction” isn’t really about morality at all.

MARTIN: No. My choice for Number 2 is Terrence Malick‘s adaptation of James Jones’ novel, “The Thin Red Line.” There are many great actors in this movie, including Sean Penn, Nick Nolte, John Savage, Jim Caviezel and others, but there’s no star. The film has a deliberately loose structure, and the story is told through multiple voiceovers and points of view. “The Thin Red Line” is actually the story of every soldier who took part in the endless battle to secure Guadalcanal.

CLIP

MARTIN: “The Thin Red Line” works very differently from most films. As you watch it you wonder: What is narrative in movies? Is it everything, and if so, is there only one way to handle it? I realize now that each of the four top movies on my list moves at a very slow tempo. If Malick had just done a straightforward narrative, could he ever have achieved the kind of poetry he does here, or made a film where you really come to see the world as a primeval place? I don’t think so.

ROGER: You know, I was thinking that, too, about your top four films, because in your films characters are very much in the foreground. Your films are about people —

MARTIN: Yes.

ROGER: — and about their souls, their guilt, their anguish. And here these people are at arms length. I loved the film too, because once again though its kind of like a dream. The narrator comes down from above and thinks about this material, rather than really being up to his neck in it.

MARTIN: Well, it takes you to a place in time. It takes you to a place You begin to think about you know, what are we as human beings, what are these soldiers doing on this primeval island?

ROGER: Do you think that audiences are open-minded when they see a film that doesn’t play just like a standard TV movie?

MARTIN: No, I’m worried that they’re not at this point. That’s what worries me.

ROGER: Yeah. I worry about that, too.

MARTIN: I’m very worried. That’s why I think “The Thin Red Line” is so important. You could come in the middle of it, you can watch it. It’s almost like an endless picture. It has no beginning and no end. People say, “Well, sometimes I can’t tell whose voiceover it is.” It doesn’t matter. It’s everybody’s voiceover.

Segment IV

MARTIN: Now I’m cheating a bit with my choice for the Number 1 film in the ’90s, because it was actually made in ’86. But it didn’t really become widely known in the United States until the early ’90s, which is when I saw it for the first time. It’s called “Horse Thief,” and it was made in Tibet by the mainland Chinese director Tian Zhuangzhuang. The story of the film is as simple and elemental as the lives of the people it depicts: a man is ostracized from his tribe for stealing horses, his living conditions become so severe that his son dies, he repents and is accepted back into the fold, and he’s forced to steal horses again to keep his second child alive.

CLIP

MARTIN: Now, I have a great interest in anthropology, and Tian takes you inside a culture that, initially, felt as distant to me as the surface of the moon. And because he stays so simple and so specific, the point of view becomes universal. This is what life is all about: struggling to keep your family alive. “Horse Thief” was a real inspiration to me. It’s that rare thing: a genuinely transcendental film.

ROGER: This movie is like an Italian neo-realist film. It made me think of “The Bicycle Thief,” although it’s more despairing even than “The Bicycle Thief.” It’s about people who are hungry and who are cold. He’s walking around in the snow barefoot at one time. And his choice is be a horse thief or be dead you know, be a horse thief or my child starves and he’s already lost one child.

MARTIN: Right.

ROGER: And he’s up against the absolute extremities of economic desperation.

MARTIN: Yeah. The director made “The Blue Kite,” back in ’93, right afterwards, which is a similar way into that society a very interesting way, where he shows you the microcosm and you get the whole macrocosm from it. Unfortunately since then he hasn’t been making pictures in mainland China.

ROGER: Maybe because he was too perceptive in these two films.

MARTIN: Yeah.

ROGER: That’s the problem in China. We get great films out of China, then their directors suddenly have to retire.

MARTIN: Can’t work. Yeah, exactly.

ROGER: But we have so many of these second hand pop images of China which are totally irrelevant. When you look at a film like this you realize these are people leading their daily lives. This is the information we don’t have when we look at the news —

MARTIN: Exactly.

ROGER: — or when we try to make sense out of the newspaper.

MARTIN: Exactly.

ROGER: Okay. Now for my Number 1 film of the 1990s, and my choice isn’t a fiction film, although it plays like one, but a documentary, named “Hoop Dreams,” from 1994. It started as a half-hour documentary about two inner city kids named William Gates and Arthur Agee, who were promising basketball players in junior high school. But then the film just kept on growing as it followed their lives covering almost five years –as they’re both recruited by a suburban high school basketball powerhouse, and fate makes a twist in their destinies.

CLIP

ROGER: To me the greatest value of film is that it helps us break out of our boxes of time and space, and empathize with other people — it lets us walk in someone else’s shoes. “Hoop Dreams,” made by Steve James, Frederick Marx and Peter Gilbert, gave me that gift.

MARTIN: Well, I think it’s a extraordinary film. I mean, you have real people becoming dramatic characters. You follow their lives like everyone’s life I think is a drama in a way. And the dedication of the filmmakers was remarkable. It reminds me Goes back to Flaherty where they live with the people and stay with them for years. Again, this is a new way, a new interesting look at story telling. And what’s great too is you begin to see the relationships in the family and how they change, the boy and his father.

ROGER: When we reviewed the movie on this show Gene Siskel said that the best scene for him was where the mother turns out to have been attending nursing school —

MARTIN: Oh, that was a great scene!

ROGER: — and she has her graduation. And he says, “That’s where the crowd should have been, not at the basketball game.”

MARTIN: Just catches you, that scene.

Segment V

ROGER: Martin Scorsese and I have discussed the top four titles on our lists of the best films of the 1990s, and now let’s go through our complete lists.

Number 10 on my list — Oliver Stone’s “JFK,” a dazzling stylistic recreation of the paranoia, suspicion and mystery that still surround the Kennedy assassination.

Number 9 — Spike Lee‘s “Malcolm X,” with Denzel Washington’s great performance as the charismatic black leader who provided an angrier and more radical alternative to the voice of Martin Luther King.

Number 8 — “Leaving Las Vegas,” with its great performances by Nicholas Cage as a suicidal alcoholic, and Elisabeth Shue as the Las Vegas call girl who gently accompanies him on his doomed final journey.

Number 7 — Lars von Trier‘s “Breaking the Waves,” with Emily Watson as a simple Scottish girl from a repressive background, and Stellan Skarsgard as the oil rig worker who makes her dizzy with love.

Number 6 — of the decade’s best films, Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List,” with Liam Neeson as a daring and good-hearted man who saves the lives of 11-hundred Jews by conning the Nazis with their own cruel rules.

Number 5 — Is a trilogy: Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Three Colors Trilogy”: “Red,” “Blue” and “White,” interlocking works that dealt with the way our lives are lived at the mercy of fate, coincidence and blind chance.

And briefly again, my Number 4 — film was “Fargo,” by Joel and Ethan Coen.

Number 3 –on my list was Martin Scorsese’s “GoodFellas.”

Number 2 — was Quentin Tarantino‘s “Pulp Fiction.”

And my choice as the best film of the 1990s was Steve James’ documentary “Hoop Dreams.”

MARTIN: Here’s my complete top ten complete list.

Number 10 — is a tie between two modern American epics. The first is Spike Lee‘s “Malcolm X,” a biography of one of our most daring political leaders, the second: Michael Mann’s “Heat,” a thrilling crime drama by one of the finest filmmakers in America, with a brilliantly cold, minimal look and great performances by Bob DeNiro and Al Pacino.

Number 9 — the Coen brothers’ “Fargo.”

Number 8 — David Cronenberg‘s “Crash.” Genuinely erotic, but also profoundly disturbing, beautifully controlled, and completely unconventional.

Number 7 — Wes Anderson‘s “Bottle Rocket.” I love the people in this film, who are genuinely innocent, more than even they know.

Number 6 — Lars von Trier‘s “Breaking the Waves,” a genuinely spiritual movie that asks what is love and what is compassion?

Number 5 — Abel Ferrara‘s “Bad Lieutenant,” starring my old friend and collaborator Harvey Keitel. He’s always taken risks as an actor, and in the ’90s, in this film in particular, he really reached his prime.

Number 4 — Stanley Kubrick‘s “Eyes Wide Shut.”

Number 3 — Wu Nien-jen’s “A Borrowed Life.”

Number 2–“The Thin Red Line,” by Terrence Malick.

And my Number 1 film of the decade — even though it was made in the late ’80s — Tian Zhuangzhuang’s “Horse Thief.”

ROGER: So, good video-rental ideas. And thanks for being here in the balcony, Marty. We’ve known each other a long time, and it was really an honor for me to invite you to share in this program.

MARTIN: Thank you. It was an honor for me, too, Roger.

******************