“The Bicycle Thief” is so well-entrenched as an official masterpiece that it is a little startling to visit it again after many years and realize that it is still alive and has strength and freshness.

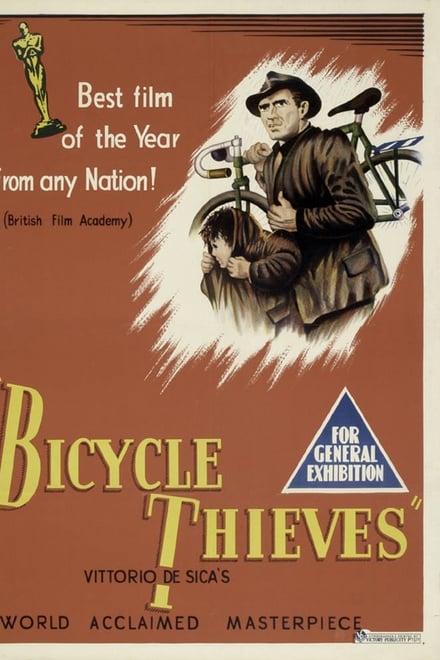

Given an honorary Oscar in 1949, routinely voted one of the greatest films of all time, revered as one of the foundation stones of Italian neorealism, it is a simple, powerful film about a man who needs a job.

The film, now being re-released in a new print to mark its 50s anniversay, was directed by Vittorio De Sica, who believed that everyone could play one role perfectly: himself. It was written by Cesare Zavattini, the writer associated with many of the great European directors of the 1940s through the 1970s. In his journals, Zavattini writes about how he and De Sica visited a brothel to do research for the film–and later the rooms of the Wise Woman, a psychic, who inspires one of the film’s characters. What we gather from these entries is that De Sica and his writer were finding inspiration close to the ground in those days right after the war, when Italy was paralyzed by poverty.

The story of “The Bicycle Thief” is easily told. It stars Lamberto Maggiorani, not a professional actor, as Ricci, a man who joins a hopeless queue every morning looking for work. One day there is a job–for a man with a bicycle. “I have a bicycle!” Ricci cries out, but he does not, for it has been pawned. His wife Maria (Lianella Carell) strips the sheets from their bed, and he is able to pawn them to redeem his bicycle; as he glances through a window at the pawn shop, we see a man take the bundle of linen and climb up a ladder to a towering wall of shelves stuffed with other people’s sheets.

The bicycle allows Ricci to go to work as a poster-hanger, slapping paste on walls to stick up cinema advertisements (a large portrait of Rita Hayworth provides an ironic contrast between the world of Hollywood and the everyday lives of neorealism). Maria, meanwhile, goes to thank the Wise Woman, who predicted that Ricci would get a job. Ricci, waiting for her impatiently, finally leaves his bicycle at the door while he climbs upstairs to see what’s keeping her; De Sica is teasing us, since we expect the bike to be gone when Ricci returns, and it’s still there.

Then, of course, it is stolen, no doubt by another man who needs a job. Ricci and his small, plucky son Bruno (Enzo Staiola) search for the bicycle, but that’s an impossible task in the wilderness of Rome, and the police are no help. Finally Ricci gives up: “You live and suffer,” he tells Bruno. “To hell with it! You want a pizza?” In a scene of great cheer, they eat in a restaurant, Bruno even allowed to drink a little wine; the boy looks wistfully at a family eating platters of pasta, and is told by his father, “To eat like that, you need a million lira a month at least.”

A little later, to his astonishment, Ricci spots the bicycle thief, and pursues him into a brothel. An ugly crowd gathers. A cop arrives, but can do nothing, because there is no evidence and only Ricci as witness. And then, in the famous closing sequence of the movie, Ricci is tempted to steal a bicycle himself, continuing the cycle of theft and poverty.

This story is so direct it plays more like a parable than a drama. At the time it was released, it was seen as a Marxist fable (Zavattini was a member of the Italian communist party). Later, the leftist writer Joel Kanoff criticized the ending as “sublimely Chaplinesque but insufficiently socially critical.” David Thomson found the story too contrived, and wrote, “the more one sees ‘Bicycle Thief,’ the duller the man becomes and the more poetic and accomplished De Sica’s urban photography seems.”

True, Ricci is a character entirely driven by class and economic need. There isn’t a lot else to him, although he comes alive in the pizzeria scene. True, the movie doesn’t make a point of contrasting his poverty with high-living millionaires (wealth is illustrated as the ability to buy a plate of spaghetti). But if the film is allowed to wait long enough–until the filmmakers are dead, until neorealism is less an inspiration than a memory–“The Bicycle Thief” escapes from its critics and becomes, once again, a story. It is happiest that way.

And its influence isn’t entirely in the past. One of the 1999 Oscar nominees for best foreign film is “Children of Heaven,” from Iran, about a boy who loses his sister’s shoes. In it there is a lovely passage where the father lifts his boy onto the crossbar of his bicycle and pedals to a rich neighborhood, looking for work. The sequence resonates for anyone who has seen “The Bicycle Thief.” Such films stand outside time. A man loves his family and wants to protect and support them. Society makes it difficult. Who cannot identify with that?

Vittorio De Sica (1902-1974) was a handsome man, much in demand as an actor, whose first films as a director were light comedies like the ones he often worked in. Perhaps the harsh reality of World War Two jarred the optimism needed for such stories, and in 1942 he made “The Children are Watching,” a film that came soon after Visconti’s “Ossessione.” The Visconti film, based on James M. Cain’s hard-boiled novel The Postman Always Rings Twice is often named as the first of the neorealist films, although even in silent days there were films that boldly looked at everyday life in an unvarnished way.

De Sica and others often used real people instead of actors, and the effect, after decades of Hollywood gloss, was startling to audiences. Pauline Kael remembers going to see De Sica’s first great film, “Shoeshine,” in 1947, just after a lovers’ quarrel that had left her in a state of despair: “I came out of the theater, tears streaming, and overheard the petulant voice of a college girl complaining to her boyfriend, ‘Well I don’t see what was so special about that movie.’ I walked up the street, crying blindly, no longer certain whether my tears were for the tragedy on the screen, the hopelessness I felt for myself, or the alienation I felt from those who could not experience the radiance of ‘Shoeshine.’ For if people cannot feel ‘Shoeshine,’ what can they feel?”

Neorealism, as a term, means many things, but it often refers to films of working class life, set in the culture of poverty, and with the implicit message that in a better society wealth would be more evenly distributed. “Shoeshine” told the story of two shoeshine boys sent to reform school for black-marketeering; Kael’s description of it could function as a definition of the hope behind neorealism: “It is one of those rare works of art which seem to emerge from the welter of human experience without smoothing away the raw edges, or losing what most movies lose–the sense of confusion and accident in human affairs.”

“The Bicycle Thief,” De Sica’s next film, was in the same tradition, and after the lighthearted “Miracle in Milan” in 1951 he and Zavattini returned to the earlier style with “Umberto D,” in 1952, about an old man and his dog, forced out onto the streets. Then, in the view of most critics, De Sica put his special gift as a director on hold for many years, turning out more light comedies (“Marriage, Italian Style,” “Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”). The two important exceptions are “Two Women” (1961), which won Sophia Loren an Oscar for her portrait of a homeless woman during the war, and “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis” (1971), about an Italian Jewish family that tries to ignore the gathering clouds of doom. Both screenplays were by Zavattini.

“The Bicycle Thief” had such an impact on its first release that when the British film magazine Sight & Sound held its first international poll of film makers and critics in 1952, it was voted the greatest film of all time. The poll is held every 10 years; by 1962, it was down to a tie for sixth, and then it dropped off the list. Its 1999 re-release allows a new generation to see how simple, direct and true it is–“what was so special about it.”