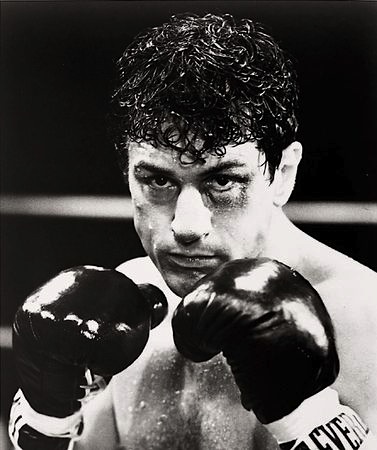

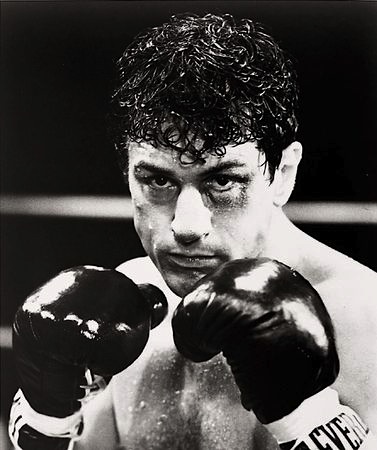

“Raging Bull” is not a film about boxing but about a man with paralyzing jealousy and sexual insecurity, for whom being punished in the ring serves as confession, penance and absolution. It is no accident that the screenplay never concerns itself with fight strategy. For Jake LaMotta, what happens during a fight is controlled not by tactics but by his fears and drives.

Consumed by rage after his wife, Vickie, unwisely describes one of his opponents as “good-looking,” he pounds the man’s face into a pulp, and in the audience a Mafia boss leans over to his lieutenant and observes, “He ain’t pretty no more.” After the punishment has been delivered, Jake (Robert De Niro) looks not at his opponent, but into the eyes of his wife (Cathy Moriarty), who gets the message.

Martin Scorsese’s 1980 film was voted in three polls as the greatest film of the decade, but when he was making it, he seriously wondered if it would ever be released: “We felt like we were making it for ourselves.” Scorsese and De Niro had been reading the autobiography of Jake LaMotta, the middleweight champion whose duels with Sugar Ray Robinson were a legend in the 1940s and ’50s. They asked Paul Schrader, who wrote “Taxi Driver,” to do a screenplay. The project languished while Scorsese and De Niro made the ambitious but unfocused musical “New York, New York,” and then languished some more as Scorsese’s drug use led to a crisis. De Niro visited his friend in the hospital, threw the book on his bed, and said, “I think we should make this.” And the making of “Raging Bull,” with a screenplay further sculpted by Mardik Martin (“Mean Streets”), became therapy and rebirth for the filmmaker.

The movie won Oscars for De Niro and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, and also was nominated for best picture, director, sound, and supporting actor (Joe Pesci) and actress (Moriarty). It lost for best picture to “Ordinary People,” but time has rendered a different verdict.

For Scorsese, the life of LaMotta was like an illustration of a theme always present in his work, the inability of his characters to trust and relate with women. The engine that drives the LaMotta character in the film is not boxing, but a jealous obsession with his wife, Vickie, and a fear of sexuality. From the time he first sees her, as a girl of 15, LaMotta is mesmerized by the cool, distant blond goddess, who seems so much older than her age, and in many shots seems taller and even stronger than the boxer.

Although there is no direct evidence in the film that she has ever cheated on him, she is a woman who at 15 was already on friendly terms with mobsters, who knew the score, whose level gaze, directed at LaMotta during their first date, shows a woman completely confident as she waits for Jake to awkwardly make his moves. It is remarkable that Moriarty, herself 19, had the presence to so convincingly portray the later stages of a woman in a bad marriage.

Jake has an ambivalence toward women that Freud famously named the “Madonna-whore complex.” For LaMotta, women are unapproachable, virginal ideals–until they are sullied by physical contact (with him), after which they become suspect. During the film he tortures himself with fantasies that Vickie is cheating on him. Every word, every glance, is twisted by his scrutiny. He never catches her, but he beats her as if he had; his suspicion is proof of her guilt.

The closest relationship in the film is between Jake and his brother Joey (Joe Pesci). Pesci’s casting was a stroke of luck; he had decided to give up acting, when he was asked to audition after De Niro saw him in a B movie. Pesci’s performance is the counterpoint to De Niro’s, and its equal; their verbal sparring has a kind of crazy music to it, as in the scene where Jake loses the drift of Joey’s argument as he explains, “You lose, you win. You win, you win. Either way, you win.” And the scene where Jake adjusts the TV and accuses Joey of cheating with Vickie: “Maybe you don’t know what you mean.” The dialogue reflects the Little Italy of Scorsese’s childhood, as when Jake tells his first wife that overcooking the steak “defeats its own purpose.”

The fight scenes took Scorsese 10 weeks to shoot instead of the planned two. They use, in their way, as many special effects as a science fiction film. The soundtrack subtly combines crowd noise with animal cries, bird shrieks and the grating explosions of flashbulbs (actually panes of glass being smashed). We aren’t consciously aware of all we’re listening to, but we feel it.

The fights are broken down into dozens of shots, edited by Schoonmaker into duels consisting not of strategy, but simply of punishing blows. The camera is sometimes only inches from the fists; Scorsese broke the rules of boxing pictures by staying inside the ring, and by freely changing its shape and size to suit his needs–sometimes it’s claustrophobic, sometimes unnaturally elongated.

The brutality of the fights is also new; LaMotta makes Rocky look tame. Blows are underlined by thudding impacts on the soundtrack, and Scorsese uses sponges concealed in the gloves and tiny tubes in the boxers’ hair to deliver spurts and sprays of sweat and blood; this is the wettest of boxing pictures, drenched in the fluids of battle. One reason for filming in black and white was Scorsese’s reluctance to show all that blood in a color picture.

The most effective visual strategy in the film is the use of slow motion to suggest a heightened awareness. Just as “Taxi Driver’s” Travis Bickle saw the sidewalks of New York in slow motion, so LaMotta sees Vickie so intently that time seems to expand around her. Normal movement is shot at 24 frames a second; slow motion uses more frames per second, so that it takes longer for them to be projected; Scorsese uses subtle speeds such as 30 or 36 frames per second, and we internalize the device so that we feel the tension of narrowed eyes and mounting anger when Jake is triggered by paranoia over Vickie’s behavior.

The film is bookmarked by scenes in which the older Jake LaMotta, balding and overweight, makes a living giving “readings,” running a nightclub, even emceeing at a Manhattan strip club. It was De Niro’s idea to interrupt the filming while he put on weight for these scenes, in which his belly hangs over his belt. The closing passages include Jake’s crisis of pure despair, in which he punches the walls of his Miami jail cell, crying out, “Why! Why! Why!”

Not long after, he pursues his brother down a New York street, to embrace him tenderly in a parking garage, in what passes for the character’s redemption–that, and the extraordinary moment where he looks at himself in a dressing room mirror and recites from “On the Waterfront” (“I coulda been a contender”). It’s not De Niro doing Brando, as is often mistakenly said, but De Niro doing LaMotta doing Brando doing Terry Malloy. De Niro could do a “better” Brando imitation, but what would be the point?

“Raging Bull” is the most painful and heartrending portrait of jealousy in the cinema–an “Othello” for our times. It’s the best film I’ve seen about the low self-esteem, sexual inadequacy and fear that lead some men to abuse women. Boxing is the arena, not the subject. LaMotta was famous for refusing to be knocked down in the ring. There are scenes where he stands passively, his hands at his side, allowing himself to be hammered. We sense why he didn’t go down. He hurt too much to allow the pain to stop.