Martin Scorsese’s “Mean Streets” is not primarily about punk gangsters at all, but about living in a state of sin. For Catholics raised before Vatican II, it has a resonance that it may lack for other audiences. The film recalls days when there was a greater emphasis on sin–and rigid ground rules, inspiring dread of eternal suffering if a sinner died without absolution.

The key words in the movie are the first ones, spoken over a black screen: “You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. All the rest is BS and you know it.” The voice belongs to Scorsese. We see Charlie (Harvey Keitel) starting up in bed, awakened by a dream, and peering at his face in a bedroom mirror. The voice was Scorsese’s, but it possibly represents words said to him by a priest.

Later Charlie talks in a voice-over about how a priest gave him the usual “10 Hail Marys and 10 Our Fathers,” but he preferred a more personal penance; in the most famous shot in the film, he holds his hand in the flame of a votive candle before the altar, testing himself against the fires of hell.

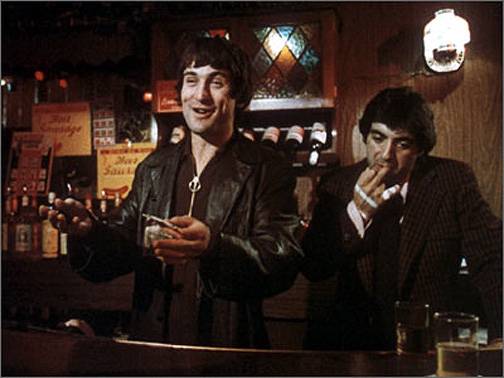

“The clearest fact about Charlie,” Pauline Kael wrote in her influential review launching the 1973 film, “is that whatever he does in his life, he’s a sinner.” The film uses lighting to suggest his slanted moral view. The real world is shot in ordinary colors, but then Charlie descends into the bar run by his friend Tony, and it is always bathed in red, the color of sex, blood and guilt.

He enters the bar in a series of shots at varying levels of slow-motion (a Scorsese trademark). He walks past his friends, exchanging ritual greetings, and eventually he gets up on the stage with the black stripper, and dances with her for a few bars of rock ‘n’ roll. He fantasizes about the stripper (Jeannie Bell), and later in the movie even makes a date with her (but fears being seen by his friends with a black woman, and stands her up). He also dreams of his cousin Teresa (Amy Robinson), who is Johnny’s sister. They have sex, but when she says she loves him, he says, “Don’t say that.”

For him both women–any woman he feels lust for–represent a possible occasion of sin, which invests them with such mystery and power that sex pales by comparison. (Immediately after dancing with the stripper, he goes to the bar, lights a match and holds his finger above it–instant penance).

Charlie walks through the movie seeking forgiveness–from his Uncle Giovanni (Cesare Danova), who is the local Mafia boss, and from Teresa, his best friend Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), the local loan shark Michael (Richard Romulus) and even from God. He wants redemption. Scorsese, whose screenplay has autobiographical origins, knows why Charlie feels this way: He knows in his bones that the church is right, and he is wrong and weak. Although he is an apprentice gangster involved with men who steal, kill and sell drugs, Charlie’s guilt centers on sex. Impurity is the real sin; the other stuff is business.

The film watches Charlie as he uneasily tries to reconcile his various worlds. He works as a collector for Giovanni, hearing the sad story of a restaurant owner who has no money. Charlie is being groomed to run the restaurant, but must obey Giovanni, who forbids him to associate with Johnny Boy (“honorable men go with honorable men”) and with Teresa, whose epilepsy is equated in Giovanni’s mind with madness.

Trouble is brewing because Johnny Boy owes money to Michael, who is growing increasingly unhappy about his inability to collect. De Niro plays Johnny almost as a holy fool: a smiling jokester with no sense of time or money, and a streak of self-destruction. The first time we see him in the film, he blows up a corner mailbox. Why? No reason. De Niro and Keitel have a scene in the bar’s back room that displays the rapport these two actors would carry through many movies. Charlie is earnest, frightened, telling Johnny he has to pay the money. Johnny launches on a rambling, improvised cock-and-bull story about a poker game, a police raid, a fight–finally even losing the thread himself.

Scorsese first displayed his distinctive style in his first feature, “I Call First / Who’s That Knocking at My Door?,” which was also set in Little Italy and also starred Keitel. In both films he uses a hand-held camera for scenes of quick movement and fights, and scores everything with period rock ‘n’ roll music (a familiar tactic now, but unheard of in 1967).

The style is displayed joyously in “Mean Streets” as Charlie and friends go to collect from a pool hall owner, who is happy to pay. But then Johnny Boy is called a “mook,” and although nobody seems quite sure what a mook is, that leads to a wild, disorganized fight. These are not smooth stuntmen, slamming each other in choreographed action, but uncoordinated kids in their 20s who smoke too much, drink too much, and fight as if they don’t want to get their shirts torn. The camera pursues them around the room, and Johnny Boy leaps onto a pool table, awkwardly practicing the karate kicks he’s learned in 42nd Street grind houses; on the soundtrack is “Please Mr. Postman” by the Marvelettes. Scorsese’s timing is acute: Cops barge in to break up the fight, are paid off by the pool hall owner, leave, and then another tussle breaks out.

Underlying everything is Charlie’s desperation. He loves Johnny and Teresa, but is forbidden to see them. He tries to be tough with Teresa, but lacks the heart. His tenderness toward Johnny Boy is shown in body language (hair tousling, back-slapping) and in a scene where Johnny is on the roof, “shooting out the light in the Empire State Building.” Charlie essentially feels bad about everything he does; his self-hatred colors every waking thought.

At one point, late in the film, he goes into the bar, orders scotch and holds his fingers over the glass as the bartender pours, copying the position of the priest’s fingers over the chalice. That kind of sacramental detail would also be a motif in “Taxi Driver,” where overhead shots mirror the priest’s-eye-view of the altar, and the hero also places his hand in a flame. Everything leads, as it must, to the violent conclusion, in which Michael, the loan shark who feels insulted, drives while a gunman (Scorsese) fires in revenge. Who can be surprised that Charlie, after the shooting, is on his knees?

Seen after 25 years, “Mean Streets” is a little creaky at times; this is an early film by a director who was still learning, and who learned so fast that by 1976 he would be ready to make “Taxi Driver,” one of the greatest films of all time, also with De Niro and Keitel. The movie doesn’t have the headlong flow, the unspoken confidence in every choice, that became a Scorsese hallmark. It was made on a tiny budget with actors still finding their way, and most of it wasn’t even shot on the mean streets of the title, but in disguised Los Angeles locations. But it has an elemental power, a sense of spiraling doom, that a more polished film might have lacked.

And in the way it sees and hears its characters, who are based on the people Scorsese knew and grew up with in Little Italy, it was an astonishingly influential film. If Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather” fixed an image of the Mafia as a shadow government, Scorsese’s “Mean Streets” inspired the other main line in modern gangster movies, the film of everyday reality. “The Godfather” was about careers. “Mean Streets” was about jobs. In it you can find the origins of all those other films about the criminal working class, like “King of the Gypsies,” “GoodFellas,” “City of Industry,” “Sleepers,” “State of Grace,” “Federal Hill,” “Gridlock'd” and “Donnie Brasco.” Great films leave their mark not only on their audiences, but on films that follow. In countless ways, right down to the detail of modern TV crime shows, “Mean Streets” is one of the source points of modern movies.