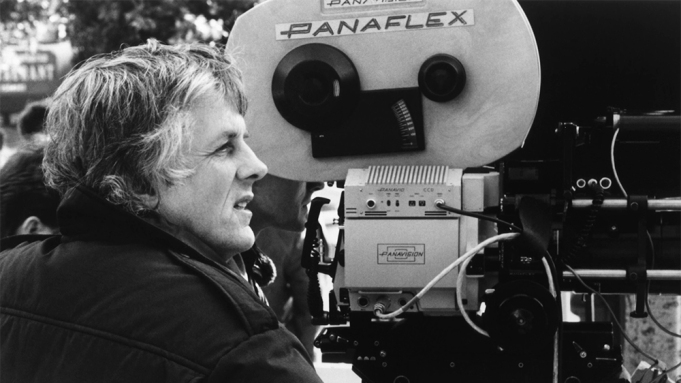

Michael Apted, the English filmmaker who died last week at 79, was thought of as a good fit for anything. Most of the time he was. That’s why he had such a long and varied career, encompassing everything from the long-running Up series of documentaries through the biographical dramas “Coal Miner’s Daughter” and “Gorillas in the Mist,” the comedies “Continental Divide” and “Critical Condition,” the fable-tinged stage adaptation “Nell,” the James Bond picture “The World is Not Enough,” the thrillers “Extreme Measures,” “Blink,” and “Class Action,” and the fantasy franchise entry “The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.”

He had an affinity for stories about women that’s rare among critically acclaimed straight auteurs today. “Coal Miner’s Daughter” won Sissy Spacek an Oscar as Best Actress; “Gorillas in the Mist” and “Nell” got nominations for Sigourney Weaver and Jodie Foster in that same category, and many of his other features centered women as well, notably the legal drama “Class Action” and the under-appreciated “Blink” (starring Madeline Stowe, written by Apted’s future wife Dana Stevens). His filmography was as broad as that of old Hollywood craftsmen like George Stevens (“Shane,” “Giant”) and William Wyler (“The Best Years of Our Lives,” “The Heiress”). But it’s hard to imagine them moving between fiction and nonfiction as seamlessly and often as Apted did, much less keeping in touch with on-the-ground, in-the-moment documentary values even while directing Hollywood blockbusters.

Revisiting Apted’s work for this appreciation drove home not just how versatile he was, but how consistent. That consistency was rooted in the idea that every movie is a documentary, if only of its own making. Apted could always be relied upon to capture a degree of physical and emotional realism in a project, no matter what it was about, or what genre he happened to be working in.

The key to his longevity was his understanding of behavior, which came out of his early success as a documentarian. He started his career as a trainee at Granada Television in Manchester. It was there that he worked on “Seven Up!” (1964), a film by Canadian filmmaker Paul Compton profiling 14 English schoolchildren from a variety of backgrounds. Apted was involved in selecting the children and jumped at the chance to direct the follow up, then continued to produce new installments every seven years, tending the project with the mix of love and duty that a parent should lavish on a child.

“Coal Miner’s Daughter,” a recent inductee into the Library of Congress’ registry of historically and artistically significant films, captures the life of country singer Loretta Lynn (Sissy Spacek) with the vividness of the great documentaries about labor struggles in rural America being released in the 1970s and ‘80s (notably Barbara Kopple’s “Harlan County, USA” and “American Dream”). There’s an awesome you-are-there feeling to the panoramic shots of the characters moving and speaking against misty green mountains in Kentucky and Virginia (with Lynn’s childhood home being replicated precisely in a Virginia warehouse), and a refreshing lack of condescension in the portrayals of poor Appalachians.

“Gorillas in the Mist” starred Weaver as the primatologist and activist Diane Fossey, who was murdered in Rwanda. Much of the film was shot on location in Rwanda, putting real gorillas in the same frame with actors whenever possible. According to a New York Times piece about the making of the film, “… crew members hiked through mud slides, dense underbrush, bamboo thickets and clumps of wild nettle to search for and film the gorillas roaming the extinct volcanoes that form one of Africa’s most spectacular borders. Because of Rwandan government restrictions on the number of people who can visit the gorillas at a time, Miss Weaver was accompanied by only a five-member film crew.”

The movie is filled with moments that blur the line between documentary and fiction, none more arresting than the scene where Weaver-as-Fossey is charged by a lumbering silverback and twists into the “submissive” position that she’d been taught by a tracker. That moment and others in the film are shot with the intent of capturing what’s happening, not worrying about whether it’s framed beautifully and flatters the star. You don’t see Weaver’s face in the wide shot of her turning away from the silverback, nor do you see it in an earlier shot of a trusting baby gorilla climbing on her shoulders to play. ”We had to choose the crew very carefully,” Apted told the Times. “We needed people with a great deal of strength. We didn’t want people who preferred the studio life. I didn’t want the movie to be Hollywood, sentimental, unreal and soft-centered.”

You can see a similar philosophy at work in other Apted features. The behaviorist’s fascination that drove the Up series also fueled much of his work in fiction. He treated places as places, not as sets or backdrops. The scenes in “Blink” that show Stowe’s character, a once-blind fiddle player, living alone in a converted industrial building and traveling the city by herself at night capture the way women must stay attuned to every movement and sound, decoding them for signs of men on the hunt. “Continental Divide” puts across the realities of being a 1980s newspaper columnist (John Belushi) as well as a naturalist (Blair Brown’s bald eagle researcher), and gives equal visual weight to the concrete canyons of Chicago and the ancient ones in the Rocky Mountains.

That most of these films have sentimental, contrived, or flat-out silly plots goes without saying. Apted’s sense of rootedness makes you believe the unbelievable, and inspires the actors to join in the illusion. And even at their most Hollywood-ish, Apted’s movies have secondary agendas that you can tell are probably the reason he said yes to the project. “Class Action” was sold as a father-daughter reconciliation movie and a high-powered acting showcase, starring Gene Hackman as a class action litigator who takes on powerful companies and institutions, and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as his attorney daughter, who has gone over to the other side. Any guess as to whether the daughter comes around by the end? Scratch the surface, though, and you find a plot that’s essentially a populist retelling of the story of the Ford motor company learning that their Pinto cars had faulty, sometimes explosive fuel tanks, but deciding not to pay for a redesign because it was more cost-effective to settle with survivors.

“Extreme Measures”—adapted from the same-named novel by screenwriter Tony Gilroy, future writer-director of “Michael Clayton”—is another Apted film that uses Hollywood packaging to get at real problems. It stars Hugh Grant as a New York emergency room doctor who discovers that homeless people are being used as experimental spinal treatment subjects against their will (Hackman returned to play the ethically challenged surgeon). The plot stirs in a lot of standard-issue thriller shenanigans, and peaks with the intrepid hero visiting an underground city of homeless people (based on mostly apocryphal tales of “mole people”); but along with Terry Gillliam’s 1991 film “The Fisher King,” “Extreme Measures” was one of but a handful of big-budget movies to not just address the homelessness epidemic, but tie it into the country’s long history of using marginalized people as guinea pigs (see also the Tuskegee experiment). The HBO film “Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned,” adapted by Walter Moseley from his collection of intertwined short stories, had a hardboiled crime-novel wrapping, but inside was an observant and often tender portrait of working Black America, with vivid and eccentric characters rarely seen on TV or in movies.

Apted’s knack for fitting his sensibility to any project did not always serve him well. The creative problems seemed to increase along with the budgets. His “Narnia” sequel has an assembly line feeling uncharacteristic of him. Ditto “The World is Not Enough,” which briefly threatens to become the most interesting of all of the Pierce Brosnan Bond films, possibly a tragic love story (and the only one with a female villain, Sophie Marceau’s Elektra Renard), then derails itself with some of the most weightless silliness this side of “Diamonds are Forever” and “A View to a Kill.”

But the longer Apted’s career went on, the more obviously he seemed to be enacting a “one for me, one for them” strategy. The “one for me” projects were often documentaries. He made two very good, general science documentaries, 1997’s “Inspirations” and 1999’s “Me & Isaac Newon” (released the same year as the Bond film). “Nell” was one of two features Apted released in 1994; the other was “Moving the Mountain,” an account of events leading up to the 1989 Tiannemen Square protests. Two of the interviews with student leaders were conducted in secret locations because the Chinese government still had them on “Most Wanted” lists. In 1992, Apted told two stories about Native Americans, one nonfiction, the other fiction. “Incident at Oglala,” about the 1975 murder of two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, came out a few months after “Thunderheart,” a fictionalized thriller version of the story of a part-Sioux FBI agent (Val Kilmer) investigating the killing of a tribal elder and wandering in to a “Chinatown”-like labyrinth of corruption and shady real estate dealings.

Apted’s first entry as director on the Up series was the immediate follow-up, “7 Plus Seven.” He would go on to direct every entry up until his death, a total of eight nonfiction features stretching through 2019’s “63 Up.” Blurring the line between cinema and television long before this became a fashionable topic of conversation among cinephiles, the series works equally well when viewed in discrete units and sequentially, from start to finish (or in bundles of installments).

Apted had a different, more critical idea of what the Up project should be about than its initiators did—and in the end, it was his vision that defined it. “It was Paul’s film,” he told Radio Times in 2012, “but he was more interested in making a beautiful film about being seven, whereas I wanted to make a nasty piece of work about these kids who have it all, and these other kids who have nothing.” Apted’s political orientation provides a framework for observations that could have become shapeless in other hands: he was initially interested in the British version of a caste system, and how it replicates itself over time despite whatever individual triumphs and tragedies an individual might suffer.

But over the decade, the series inevitably became a meditation on the relationship between story and storyteller, and on the pressures that regular folks unconnected to the film industry feel when they become famous, or semi-famous. As the series unfolds, some subjects drop out and reappear, others stay gone, others die. All retell the same stories and reiterate the same dreams and regrets from one installment to the next, often with newfound insight (or honesty). Apted’s archives are always prepared to juxtapose the distant past, the recent past, and the present.

And of course, the series is about time: what it does to our relationship to the movie image, what it does to our memories, what it does to us period. This site’s founder was obsessed with that aspect. He considered Apted’s “Up” documentaries to be among the greatest achievements in motion picture history, and put “28 Up” on his 1991 list of the greatest films of all time. It seems fitting to let Roger Ebert, Apted’s greatest champion, have the final word here.

“No other film I have ever seen does a better job of illustrating the mysterious and haunting way in which the cinema bridges time,” he wrote. “The movies themselves play with time, condensing days or years into minutes or hours. Then going to old movies defies time, because we see and hear people who are now dead, sounding and looking exactly the same. Then the movies toy with our personal time, when we revisit them, by recreating for us precisely the same experience we had before. Then look what Michael Apted does with time in this documentary, which he began more than 30 years ago … The miracle of the film is that it shows us that the seeds of the man are indeed in the child. In a sense, the destinies of all of these people can be guessed in their eyes, the first time we see them. Some do better than we expect, some worse, one seems completely bewildered. But the secret and mystery of human personality is there from the first. This ongoing film is an experiment unlike anything else in film history.”