A woman called in to the Howard Stern show one morning to protest animal use in lab experiments. Stern discovered that she had a cat named (as I recall) Fluffy. She had no children. “My wish for you,” Stern said, “is that someday you have a beautiful little baby girl, and that your daughter gets a disease that can only be cured by sacrificing Fluffy. Call back and tell me how you decide.” A version of this moral dilemma lurks at the center of Michael Apted’s “Extreme Measures,” making the movie more thought-provoking than thrillers usually are. At one point the hero is asked by the villain: “If you could cure cancer by killing one person, wouldn’t you have to do that?” Well, would you? To the movie’s credit, it sees that the question is a good deal more complex than it appears.

As the movie opens, Hugh Grant plays a young New York emergency room surgeon named Guy Luthan. He gets a patient–bald, middle-aged, naked, delusional–whose symptoms confuse him. The patient eventually dies, and when Guy goes looking for the autopsy report, he is startled to discover that the body, and all records involving it, apparently have disappeared.

Many emergency-room doctors would be too busy to follow up, especially in the case of a homeless man who probably was on drugs. But Guy can’t forget the case–nor the fact that the man already had a hospital-patient tag on his wrist when he was admitted. Had this man escaped from a different hospital? Guy keeps digging, searching computer files and old records in a warehouse, despite a warning by his superior (Paul Guilfoyle) to drop the case.

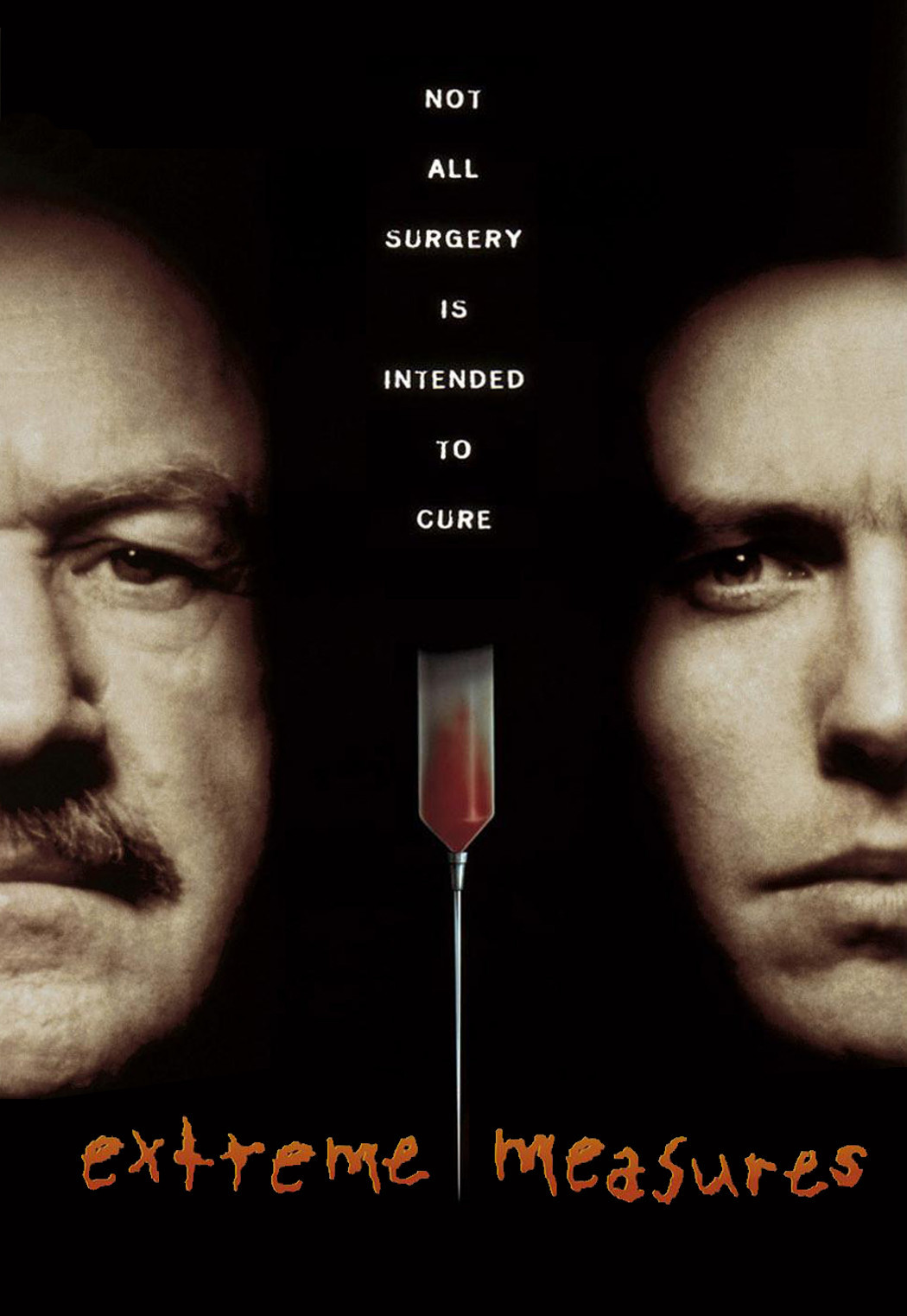

We meet, in the meantime, the distinguished medical researcher Lawrence Myrick, played by Hackman. He has just been awarded a medal in honor of his work with paralyzed rats: He’s found a way to regenerate their damaged spinal columns, so they can walk again. No prizes for guessing that Myrick may be connected with the mystery patient, and that he may have been working on him rather than on rats.

The plot develops as a version of Hitchcock’s favorite dilemma, the Innocent Man Wrongly Accused. The more Guy pushes, the more the establishment pushes back. His only friend seems to be a nurse in the E.R. (Sarah Jessica Parker) who supports him and helps him find some records. But soon Guy’s medical career is brought to a sudden halt, when the cops find cocaine in his apartment. It’s not his, but never mind: His reputation is destroyed in a second, and it is easy to read this part of the film as an emotional reflection on Grant’s own contact with overnight scandal.

Apted seems more in tune than many directors to the voodoo of location, and here (shooting exteriors in New York, interiors in Toronto), he creates a paranoid world in which Guy seems helpless to understand the forces against him. In one of the most effective sequences, his search leads him into the labyrinth beneath Grand Central Station, where mole people–the homeless who have burrowed out living quarters there–may have the clue to the dead man, and much more besides.

The movie, written by Tony Gilroy, is pitched at a higher level than most thrillers; the dialogue is literate and intelligent, and Grant is more of an everyman than an action hero (he tones down his light comedy mannerisms and emerges as a credible doctor). It’s interesting that, at the end, Apted avoids the obligatory action cliches of the usual movie thriller and goes with the strengths of his two actors: Grant and Hackman deliver well-reasoned speeches in defense of their characters.

Hackman is such a persuasive actor that when he was finished, I was almost prepared for the young doctor to cave in and admit he was right. But of course Hackman isn’t right. Is he? I found myself debating the film’s moral questions on the way out of the theater.

I’ve often thought about that Howard Stern program, and the woman asked to choose between her cat and her child. Of course, most people wouldn’t pause one second in choosing between *your* cat and their child. Or their child and your child. But what if you were told that 10 children you had never met would live if your child died? What would you say then? You’d still not sacrifice your child? Very human. What if a hundred children could be saved? A thousand? A million? On and on we talked after the movie was over, but we didn’t come up with a very satisfactory answer.