<iframe title="YouTube video player" width="510" height="413" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/8TsAnUmIzYY?rel=0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="“>

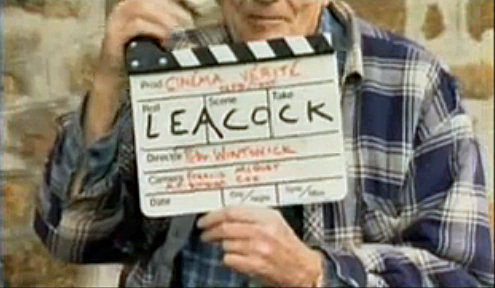

Chicago digital filmmaker Nelson Carvajal recently quoted the late Direct Cinema / Cinéma vérité pioneer Richard Leacock in a post at Free Cinema Now in which he defends — for personal, aesthetic reasons — the fashionable handheld camera technique known variously as the shaky cam, the queasy-cam and (when combined with chaotic cutting) the snatch-and-grab:

Anyone who knows my shooting style knows that I’m not a fan of tripods. To me, most static “pretty” shots that I see from other indie filmmakers represent an analogy for an elusive Hollywood-esque model of moviemaking. Ever been on a student film set and notice how much of the day goes to laboring over a shot that really doesn’t grab you in the end? We go to the movies and are swept away by the big budget vistas and then for some reason we’re convinced that our camcorder, a tripod and a light set will accomplish the same feel. And when it doesn’t, we’re surprised. But we shouldn’t be. At the end of the day, it’s all about the content of what we’re trying to show, say or provoke in an audience. So instead of trying to mimic or recreate a sense of grandness without the necessary resources (like an outrageous Hollywood budget for example), why not create our own language for the cinema? Let Hollywood make “Sucker Punch.” We’ll instead focus on breaking away and discovering new ways to tell our stories.

I suppose this is why I embrace “direct cinema” filmmaking so strongly. I love grabbing the camera and just improvising as I go. It’s a shooting style that liberates my senses; it awakens me.

David Lynch said something similar about using small handheld digital video cameras in the making of “Inland Empire.” As I wrote about his appearance with the film in Seattle back in 2007:

Lynch was enthusiastic about his experience shooting with a small digital camera (the Sony PD-150), and said he began using it to make shorts for his web site. After he’d made a few, he started thinking about them in terms of a larger framework story, and by then he was “already locked into” the digital format. He said he loved the freedom it allowed him (wait till you see the close-ups he goes for — he coulda poked somebody’s eye out!). Sure, he said, this format (it’s NOT high-definition like, say, “Miami Vice”) doesn’t have the quality of film, but it has its own qualities, its own textures. And, Lynch said, it was so easy to push and to tweak at will to get the effects he wanted. Best of all, he didn’t have to stop the actors to re-load the camera after every ten minutes of exposed film. He could keep things going for 40 minutes (sometimes shooting with three cameras simultaneously), which he thought allowed for interesting things to happen that might not have happened otherwise.

Unfortunately, by 2007, the handheld camera had already become a cliché in mainstream Hollywood pictures, as it had long been in American indie movies. As David Bordwell wrote that year: “A spectre is haunting contemporary cinema: the shaky shot.” Just last week, Matt Zoller Seitz weighed in on Salon.com, after seeing “Battle: Los Angeles” (2011):

How to describe the aggressive dreadfulness of “Battle: Los Angeles,” maybe the worst-directed Hollywood movie I’ve ever seen? Incompetent doesn’t do the trick, because it implies an inability to master basic craft. That’s not the case here. “Battle: Los Angeles” takes one of the more controversial cinematography fads of recent years — the “shaky camera and shallow focus equals ‘reality'” fad — to noxious new levels of excess. The movie is the work of professionals who decided to make their film look bad on purpose. […]

Simply put, this crap is transparently cynical and opportunistic and has become totally played-out since 1999’s “The Blair Witch Project,” arguably the hit that made home video panic-cam an official, approved technique in mainstream productions. Twelve years later, directors who keep treating it as an aesthetic security blanket — especially at the big-budget level — should be required to get a tattoo across their foreheads that reads “Hack.” Get yourself a tripod. Make a shot list. Think about where you’re putting the camera and why you’re putting it there, and try to redirect the audience’s attention by moving the camera or refocusing rather than cutting every three to five seconds. Stop covering action. Start directing again.

Even those of us who have been critical of the ubiquitous overuse of the handheld (as a reality-show gimmick used to mask a multitude of failures — DB quoted a saying of Hong Kong cinematographers: The handheld camera covers three mistakes: Bad acting, bad set design, and bad directing) know that there’s no such thing as a bad technique, there are simply bad decisions and inept applications. What works for Leacock (in a documentary showing dancing in a jazz club in 1954) or Lynch or Carvajal, may not be appropriate or effective in other circumstances.

Sure, movies like “Blair Witch” and “Cloverfield” are built on the conceit that we’re watching spontaneous videocam images shot by the fictional characters, and you either go with the concept or you vomit. But is the technique equally effective in, say, Woody Allen’s “Husbands and Wives,” Oliver Stone’s “Natural Born Killers,” Paul Greengrass’s “The Bourne Ultimatum, Lynch’s “Inland Empire,” Ryan Fleck’s “Half Nelson” (2006) … and every lo-fi “mumblecore” movie ever conceived to project an urban boho aesthetic? (Folks — Jim Jarmusch used a tripod in the 1980s and still does. And he’s more downtown than any of us will ever be. Abbas Kiarostami and Apichatpong Weerasethakul lock down their cameras more often than not.)

Please take a look at the wonderful video clip above, which Carvajal provided with his post, “Shoot and shoot and shoot.” Leacock remembers the excitement of being able to climb up on tables or mix with the dancers in the jazz club, without having to worry about bulky equipment, lights or microphones. Indeed, he’s just as excited about giving up the “freedom” of shooting without synchronized sound — and the footage from “Jazz Dance” is mostly unsynchronized. (See “Sweetgrass,” one of the best films of 2010, for a spectacular soundtrack that mixes synch footage and more poetic usages of sound, recorded on location, and layered over non-synched images.)

In the clip, of course, Leacock (who later partnered with D.A. Pennebaker) and Bob Drew are talking about documentary, journalistic filmmaking, and breaking away from the clichés of the time must surely have been liberating. As liberating as using stable camera might feel today.

I saw “Ricky” Leacock at the Telluride Film Festival in the early 1980s, where he received a tribute. He became a regular, along with Werner Herzog, another poetic documentarian who famously pronounced in his “Minnesota Declaration:

1. By dint of declaration the so-called Cinema Verité is devoid of verité. It reaches a merely superficial truth, the truth of accountants.

2. One well-known representative of Cinema Verité declared publicly that truth can be easily found by taking a camera and trying to be honest. He resembles the night watchman at the Supreme Court who resents the amount of written law and legal procedures. “For me,” he says, “there should be only one single law: the bad guys should go to jail.”

Unfortunately, he is part right, for most of the many, much of the time.

3. Cinema Verité confounds fact and truth, and thus plows only stones. And yet, facts sometimes have a strange and bizarre power that makes their inherent truth seem unbelievable.

4. Fact creates norms, and truth illumination.

5. There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.

6. Filmmakers of Cinema Verité resemble tourists who take pictures amid ancient ruins of facts.

So, you see, there is plenty of room for aesthetic, philosophical and technical interpretation. For me, it depends on the individual film under observation.

When I made my semi-facetious Dogme 09.8 Manifesto: Ten limitations for better movies, the first item on my list was:

1. Get a tripod. Learn how to use it. Human beings do not feel their heads bobbling around all the time. If they did, they’d throw up a lot more. The hand-held camera, once a legitimate tool, has been overused to death. It is beyond a cliché, beyond a “certain tendency” — it has become the most obtrusive, commonplace annoyance in modern films, a hallmark of visual illiteracy. Audiences should throw things at the screen every time they notice handheld camerawork.

That last sentence summarizes my chief objection to the overuse of handheld camerawork in all kinds of films in the last 20 or 30 years. When you see handheld camerawork, you immediately become aware that someone is walking around with a camera. It is a self-conscious, obtrusive technique in most situations. The question is whether it may be more effective to just put the thing down — on a table, a chair, a box — to get the camera out of the way. Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t. Consider other options, not just the easiest, most common one.

I haven’t seen Nelson Carvajal’s work (though I enjoy his blog posts and Facebook updates). But from what he wrote, I trust he knows what he’s doing. The shaky-cam is dead. Let’s see someone re-invent it. Again.