In the movies, and unfortunately in life, we tend to accept the easy falsehood that someone who behaves badly in one respect must be bad in others, even if they’re totally unrelated. So, if a person is a gambler, he must be a drunk. If he’s a pedophile, he must be a murderer. If he’s a cigarette smoker (in the movies, at least), he must be corrupt conspirator of some kind.

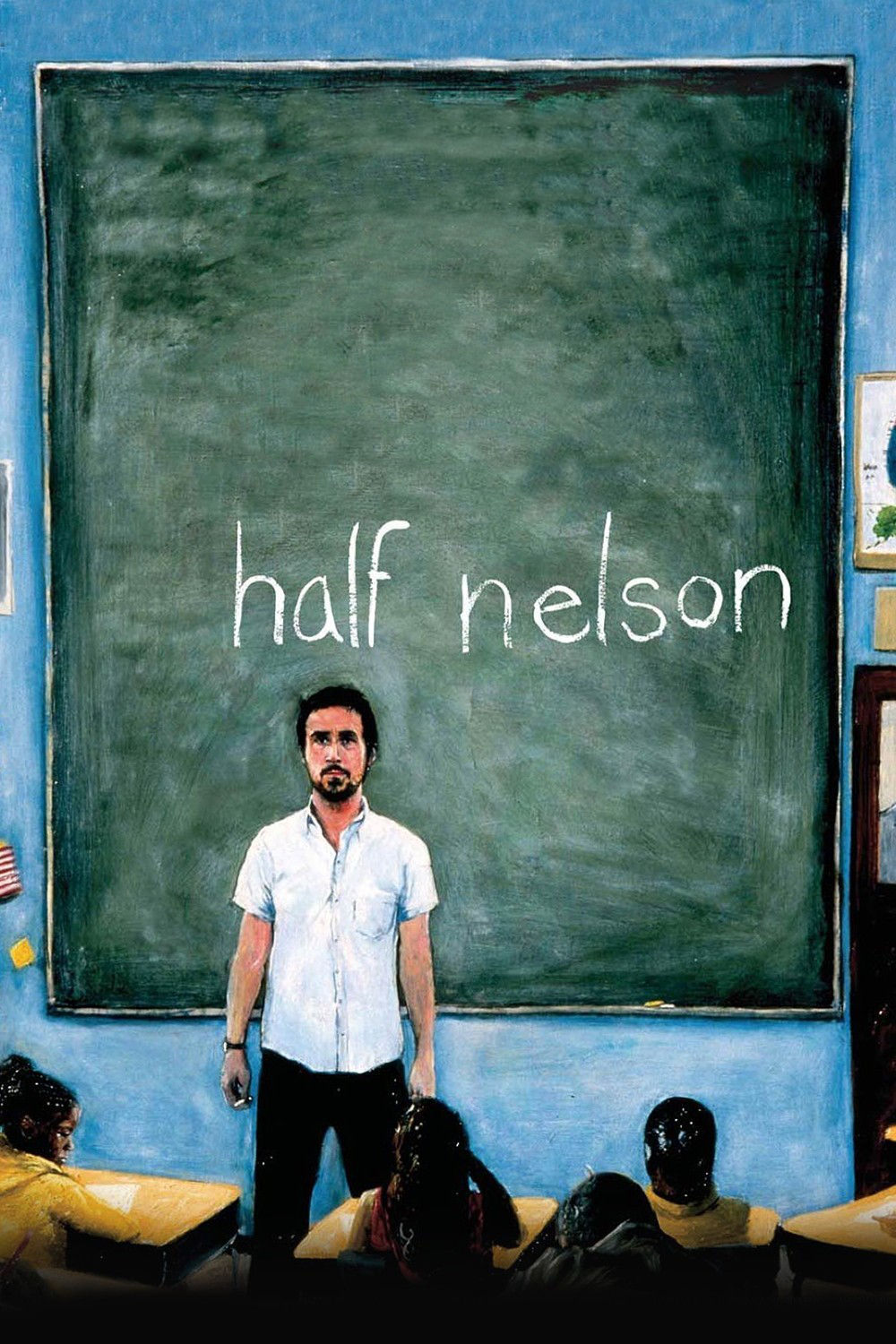

In a black-and-white world, human flaws are not allowed. In order to do good, a person must himself be a paragon of goodness. “Half Nelson,” the miraculous movie by Ryan Fleck and Anna Boden, is about a junior high schoolteacher who smokes. Crack. And the thing is, he’s a good teacher, even if (or, rather, because) he doesn’t always stick to the district-approved syllabus.

Dan (Ryan Gosling) wakes up on the hardwood floor of his apartment in an open short-sleeved shirt and white jockey shorts. And then he somehow gets himself to work, dragging himself up the stairs like an escapee from a George Romero movie. He’s wan and thin, and his bruised blue eyes look like they could roll back in his head at any minute. But once he gets started talking about the dialectics of power and world politics, he comes alive. Back in the teachers’ lounge, or alone in his car, for lunch, he’s halfway back to the realm of the undead again.

Dan does some bad things — reckless, destructive and irresponsible things. But is he a bad guy? I don’t think so. And neither do his students — especially Drey (Shareeka Epps), the stoic and rather sullen student who finds her basketball coach half-unconscious on the floor of a school restroom after a game. She gets him a wet paper towel. He says he’s sorry. Neither of them makes a big thing about it. Somehow, it brings them closer. “See you tomorrow,” she says when he drops her off at home.

Dan is tossed out of a game after throwing a ball at a ref. Off court, he punches a wall. Afterward, on the ride home, Dan tries to give Drey the requisite “do as I say, not as I do” lecture, telling her that he shouldn’t have lost his temper and thrown the ball at the ref. She says it must feel good, though, to just “get it out,” but he reminds her there are other ways of getting it out.

“Right, like you do,” she says. Her tone is almost but not quite neutral; not accusatory, but with a subtle yet affectionate rebuke. “Look, just because you know that one thing about me …,” Dan says. “One thing doesn’t make a man.” Pause. She frowns, looks at him. A smile breaks across her face and she quietly snickers: ” ‘One thing doesn’t make a man?’ You know I’m just talking about your hand, right?” Dan, knowing she’s got him, also smiles and tries unconvincingly to recover: “Yeah, I knew that …”

Everything that makes this movie so terrific is right there in that scene, in the interplay between these two characters — and these two actors. The whole sequence is shot from the back seat, in separate shots, so that only part of each character’s face is visible at any given moment. There’s a lot going on between these two, but it’s mostly through indirection.

“Ryan Gosling” may sound like the name of a teen heartthrob, but this performance, coming after “The Believer,” proves he’s one of the finest actors working in contemporary movies. And he’s only 25 years old. Epps (no relation to Omar) is his perfect foil, as the kid for whom Dan cares the most. She doesn’t say much, but she doesn’t have to. Drey’s got Dan’s number, and may be the only person on earth who comes close to understanding who he is.

“Half Nelson” isn’t one of those “inspirational teacher/mentor” movies — at least not in any generic or conventional sense. There’s no triumph, no breakthrough, no by-the-numbers victory in test scores or on the basketball court. This movie isn’t about those things, but is concerned with an even greater achievement that is generally unacknowledged: how people — flawed, miserable, frustrated people — go to work every day and find a way to care about something beyond themselves, despite themselves.

Dan himself is confused about his relationship to Drey. He knows he can’t save the world; he just wants to do right by this one girl. But there are boundaries. He’s her teacher, after all, not her friend. But Drey needs both, and she’s not going to let job descriptions get in her way.

Watching Dan teach — or some of the oral reports about history and politics delivered by his students — the proverbial line between the personal and the political becomes meaningless, because they can’t help being one and the same. The slogan says: “Think globally, act locally.” But thought and action begin in the same place: inside one’s own, messed-up head.