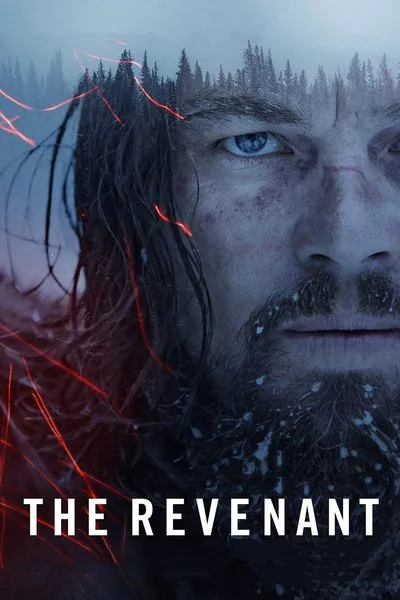

Great film has the power to convey the unimaginable. We sit in the comfort of a darkened theater or our living room and watch protagonists suffer through physical and emotional pain that most of us can’t really comprehend. Too often, these endurance tests feel manipulative or, even worse, false. We’re smart enough to “see the strings” being pulled, and the actor and set never fades away into the character and condition. What’s remarkable about Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu’s “The Revenant” is how effectively it transports us to another time and place, while always maintaining its worth as a piece of visual art. You don’t just watch “The Revenant,” you experience it. You walk out of it exhausted, impressed with the overall quality of the filmmaking and a little more grateful for the creature comforts of your life.

Iñárritu and co-writer Mark L. Smith set their tone early, staging a breathtaking assault on a group of fur trappers by Native Americans, portrayed not just as “enemies” but a violent force of nature. While a few dozen men are preparing to pack up and move on to their next stop in the great American wilderness, a scene out of “Apocalypse Now” unfolds. Arrows pierce air and flesh as the few surviving men flee to a nearby boat. It turns out that the tribe is seeking a kidnapped daughter of its leader, and will kill anyone who gets in their way. At the same time, we learn that one of the trappers, Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio) has a half-Native American son named Hawk (Forrest Goodluck).

Low on men and hunted, the expedition leader Andrew Henry (Domhnall Gleeson) orders that their crew return to its base, a fort in the middle of this snowy wilderness. John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) disagrees, and the seeds of dissent are planted. He doesn’t trust Henry, and he doesn’t like Glass. In the midst of these discussions, Glass is away from the crew one day when he’s brutally attacked by a bear—the sequence is, without hyperbole, one of the most stunning things I’ve seen on film in a long time, heart-racing and terrifying. Glass barely survives the attack. It seems highly unlikely that he’ll make it back to the base. With increasingly dangerous conditions and a tribe of killers on their heels, they agree to split up. Most of the men will go back first while Fitzgerald, Hawk and a young man named Bridger (Will Poulter) will get a sizable fee to stay with Glass until he dies, giving him as much comfort as possible in his final days and the burial he deserves.

Of course, Fitzgerald quickly tires of having to watch a man he doesn’t care about die. He kills Hawk in front of an immobile Glass and then basically buries Hugh alive. As Bridger and Fitzgerald head back, Glass essentially rises from the dead (the word revenant means “one that returns after death or a long absence”) and begins his quest for vengeance. With broken bones, no food, and miles to go, he pulls himself through snow and across mountains, seeking the man who killed his son. He is practically a ghost, a man who has come as close to death as one possibly can but is unwilling to go to the other side until justice is done.

The bulk of “The Revenant” consists of this torturous journey, as Glass regains his strength and gets closer to home through sheer force of will. Iñárritu’s Oscar-winning cinematographer for “Birdman,” Emmanuel Lubezki (who also took a trophy for “Gravity” the year before and could easily make it three in a row for this work) shoots “The Revenant” in a way that conveys both the harrowing conditions and the artistry of his vision. The sky seems to go on forever; the horizon is neverending. He works in a color palette provided by nature, and yet enhanced. The snow seems whiter, the sky bluer. Many of his shots, especially in times of great danger like the opening attack and the bear scene, are unbroken—placing us in the middle of the action.

At other times, Lubezki’s choices recall his work on “The Tree of Life,” especially in scenes in the second half when Glass’s journey gets more mystical. And that’s where the film falters a bit. Iñárritu doesn’t quite have a handle on those second-half scenes and the 156-minute running time begins to feel self-indulgent as the film loses focus. When it centers on the conditions and the tale of a man unwilling to die, it’s mesmerizing. I just think there’s a tighter version, especially in the mid-section, that would be even more effective.

About that man: So much has been made of this film being DiCaprio’s “Overdue Oscar” shot that I feel like his actual work here will be undervalued. Make no mistake. Should he win, it will not be some “Lifetime Achievement” win as we’ve seen in the past for actors who we all thought should have won for another film (Paul Newman, Al Pacino, etc.). He’s completely committed in every terrifying moment, pushing himself further than he ever has before as an actor. Even just the physical demands of this protagonist would have been enough to break a lot of lesser actors, but it’s the way in which DiCaprio captures his internal fortitude that’s captivating—his body may be broken, but we believe he is unwilling to give up.

The minimal supporting cast is good, and it’s nice to see Gleeson continue to have an incredible 2015 (also in “Brooklyn,” “Ex Machina” and “Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens”). Tom Hardy is less effective, often going a little too heavy on the tics (wide eyes, shot up-close), but I think that’s a fault of the direction and not one of our best actors. In the end, this is DiCaprio’s film through and through, and he nails every challenging beat, literally throwing himself into this character that demands more of him physically than any other before.

What would you do for vengeance? What conditions could you surmount to get it? Or would you just give up? Our favorite films often drop questions like these into our lives, allowing us to appreciate the world a little differently than before we saw them. “The Revenant” has this power. It lingers. It hangs in the back of your mind like the best classic parables of man vs. nature. It will stay there for quite some time.