The first time we see Michael Keaton in his tighty-whities in “Birdman,” it’s from behind. His character, a formerly high-flying movie star, is sitting in the lotus position in his dressing room of a historic Broadway theatre, only he’s levitating above the ground. Bathed in sunlight streaming in from an open window, he looks peaceful. But a voice inside his head is growling, grumbling, gnawing at him grotesquely about matters both large and small.

The next time we see Keaton in his tighty-whities in “Birdman,” he’s dashing frantically through Times Square at night, having accidentally locked himself out of that same theatre in the middle of a performance of a Raymond Carver production that he stars in, wrote and directed. He’s swimming upstream through a river of gawking tourists, autograph seekers, food carts and street performers. But despite the chaos that surrounds him, he seems purposeful, driven and–for the first time–oddly content.

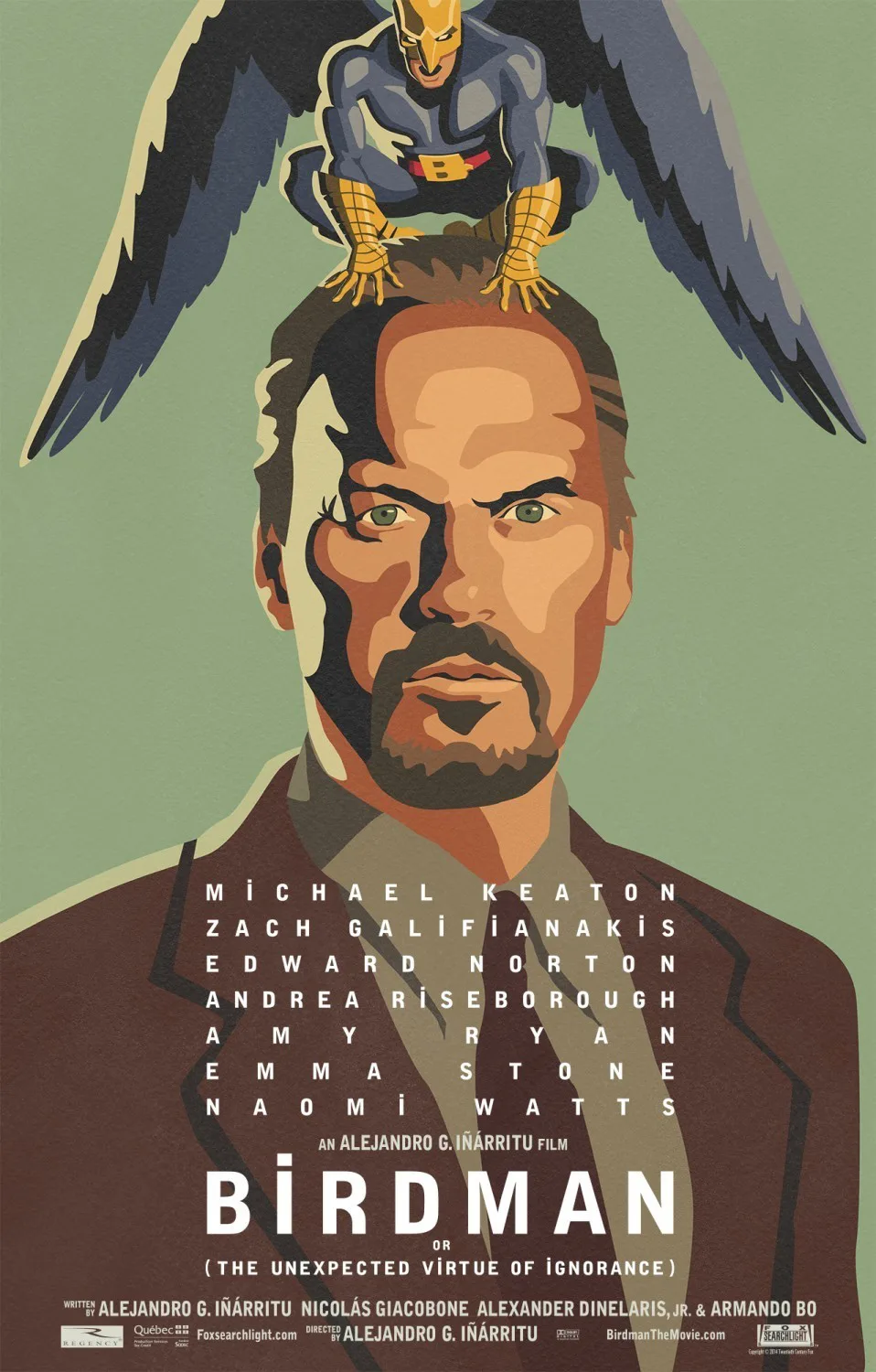

These are the extremes that director Alejandro G. Inarritu navigates with audacious ambition and spectacular skill in “Birdman”–the full title of which is “Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance).” He’s made a film that’s both technically astounding yet emotionally rich, intimate yet enormous, biting yet warm, satirical yet sweet. It’s also the first time that Inarritu, the director of ponderous downers like “Babel” and “Biutiful,” actually seems to be having some fun.

Make that a ton of fun. “Birdman” is a complete blast from start to finish. The gimmick here–and it’s a doozy, and it works beautifully–is that Inarritu has created the sensation that you are watching a two-hour film shot all in one take. Working with the brilliant and inventive cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (who won an Oscar this year for shooting “Gravity” for Inarritu’s close friend and fellow Mexican director Alfonso Cuaron), Inarritu has constructed the most delicate and dazzling high-wire act. And indeed, before shooting began, the director sent his cast a photo of Philippe Petit walking a tightrope between the World Trade Center towers as inspiration.

Through impossibly long, intricately choreographed tracking shots, the camera swoops through narrow corridors, up and down tight stairways and into crowded streets. It comes in close for quiet conversations and soars between skyscrapers for magical-realism flights of fancy. A percussive and propulsive score from Antonio Sanchez, heavy on drums and cymbals, maintains a jazzy, edgy vibe throughout. Sure, you can look closely to find where the cuts probably happened, but that takes much of the enjoyment out of it. Succumbing to the thrill of the experience is the whole point.

Just as thrilling is the tour-de-force performance from Keaton in the role of a lifetime as Riggan Thompson, a washed-up actor trying to regain the former glory he achieved as the winged action hero Birdman. The film follows the fraught early going of his Broadway debut which is also his last shot at greatness–although his on-screen alter ego doesn’t help much by voicing his fears and making him doubt himself incessantly. Yes, it’s knowingly amusing that Keaton, who peaked 20-plus years ago as a superhero, is playing an actor who peaked 20-plus years ago as a superhero. Although I’d happily argue that Keaton’s Batman for Tim Burton in 1989 is THE definitive performance of the iconic character–but that’s a whole ‘nother conversation for another time.

Or is it? While “Birdman” exists in its own meticulously realized world, it’s very much of this time and place from a pop-culture perspective, with references to other real-life actors like Robert Downey Jr. and Michael Fassbender who’ve enjoyed enormous success when they’ve donned the superhero duds. The script from Inarritu, Nicolas Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris and Armando Bo is cleverly meta without being too cutesy and self-satisfied.

Keaton gets to toy with his persona a bit–as well as acknowledge how comparatively quiet his career has been in recent years–but seeing him in seasoned form provides its own joy. He’s still hyper-verbal and playful and he can still be amusing and lacerating in his delivery, but there’s a wry wistfulness and even a desperation in the mix now that’s achingly poignant.

Also confronting his real-life reputation is Edward Norton as Mike Shiner, the brilliant but infamously capricious actor who steps in as Riggan’s co-star just as previews are about to begin on his labor-of-love production of “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” Norton, who’s come with the baggage of being difficult and demanding over the years, finds just the right balance between arrogance and sincerity.

Besides, they need each other, as they find in the days leading up to opening night. They all need each other. Inarritu has amassed a tremendous supporting cast and made ridiculous technical demands of them, yet they’ve all more than risen to the occasion and relished the chance to shine.

Zach Galifianakis plays strongly against type as Riggan’s manager and the rare voice of reason in the middle of all this madness. Emma Stone is adorable as Riggan’s world-weary, wise-ass daughter who also serves as his assistant. (She and Norton have crackling chemistry in a couple of crucial scenes.) Amy Ryan does wonders with her brief screen time as Riggan’s ex-wife; she fleshes him out and allows us to see both the selfish and the good in him. And Naomi Watts, who starred in Inarritu’s wrenching “21 Grams,” gets to play both light and heavy moments as a neurotic fellow cast member.

It’s powerfully clear that they all worked their asses of to make this complicated thrill ride look effortless. The result is one of the best times you’ll have at the movies this year–which might even be the best movie this year.