Enough time has passed in cinema history for the name Merchant-Ivory to have become an adjective. It’s made from the names of Director James Ivory and producer Ismail Merchant, who worked together from the 1960s through Merchant’s death in 2005. Critics use the hyphenate to refer to “costume dramas” generally, and to any historical drama they want to subtly denigrate for being handsomely produced but safe. Sometimes, when the phrase is used that way, you can’t be sure if the writers really know where the term comes from, much less that it was the name of a production company that, for a couple of decades, was as close to a foolproof, get-them-in-the-door “brand” as you could find in the arthouse world. Merchant, who was from Bombay, produced 42 movies under this banner. Ivory, an unassuming but steely man from Oregon, directed 30. Sixteen were written by the same woman, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (a cultural polyglot who merits her own movie; she was born in Germany to Jewish parents who emigrated to England, then married Indian architect Cyrus Jhabvala and moved to New Delhi, where she wrote novels about Indian subjects, including the Booker Prize-winning Heat and Dust, which Merchant Ivory made into a movie). The scores for 21 of the movies were done by Richard Robbins. That’s incredible continuity of vision as a team, even by the standards of auteurist analysis.

The best of Merchant Ivory’s output felt timeless even on first release, and would be considered classics in any era, including “A Room with a View,” “Howard’s End,” “Maurice,” and “The Remains of the Day.” And many of the others, including “Heat and Dust,” “The Bostonians,” “Surviving Picasso,” and “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries,” are underrated and due for rediscovery. “Merchant Ivory,” a documentary by Stephen Soucy about the production company and the lead duo behind it, should be endearing for anybody who spent a lot of time in art house movie theaters in the 1980s and ’90s, the duo’s heyday.

As an official certification of the team’s significance, this documentary does the job, though there are times when it feels like a very good (and handsomely produced) box set supplement about important personalities involved in the movies, more so than an all-things-to-all-viewers experience that can satisfy as a biography, a film production company history, an exploration of group dynamics between artists, and an explanation of what, exactly, the Merchant-Ivory crew did that was so intoxicating to millions. If you’re looking for a film to explain the artistic significance of the duo and their place within the larger film ecosystem, you’re probably better off doing your own research, and reading reviews of the movies from different eras.

The interviews are the best part of the film, which lacks the sleek, focused, concentrated quality of the best Merchant Ivory movies but succeeds on its own terms as sort of a “hangout” movie, non-fiction division. Hugh Grant, one of many now-super-famous actors to become an integral part of a Merchant Ivory production (he was half of the romantic duo in “Maurice,” a key work of gay cinema in the ’80s), talks about a kind of sublimated lustfulness that could be detected on sets filled with great looking people in elegant, often formal attire, and also of Merchant’s legendary frugality. “Very often, films got made and you’d say, ‘Who’s the money behind this film?’ and at that point, there was no money. He still had to get it.” Vanessa Redgrave, who acted in three of the duo’s films (including “The Ballad of the Sad Cafe,” one of only two features that Merchant directed himself), is a spiky and rather controlling presence on the documentary set. Ivory, of course, was gay but not public about it; he eventually became the oldest Oscar winner after penning the original screenplay for “Call Me by Your Name.” Merchant was also gay, and the two were professional and romantic partners during much of their association. There’s talk of romantic melodrama that affected the partnership, it sounds complex and painful enough that one almost wishes somebody would make a fictional film about it. (One witness to it describes it as “dreadful.”)

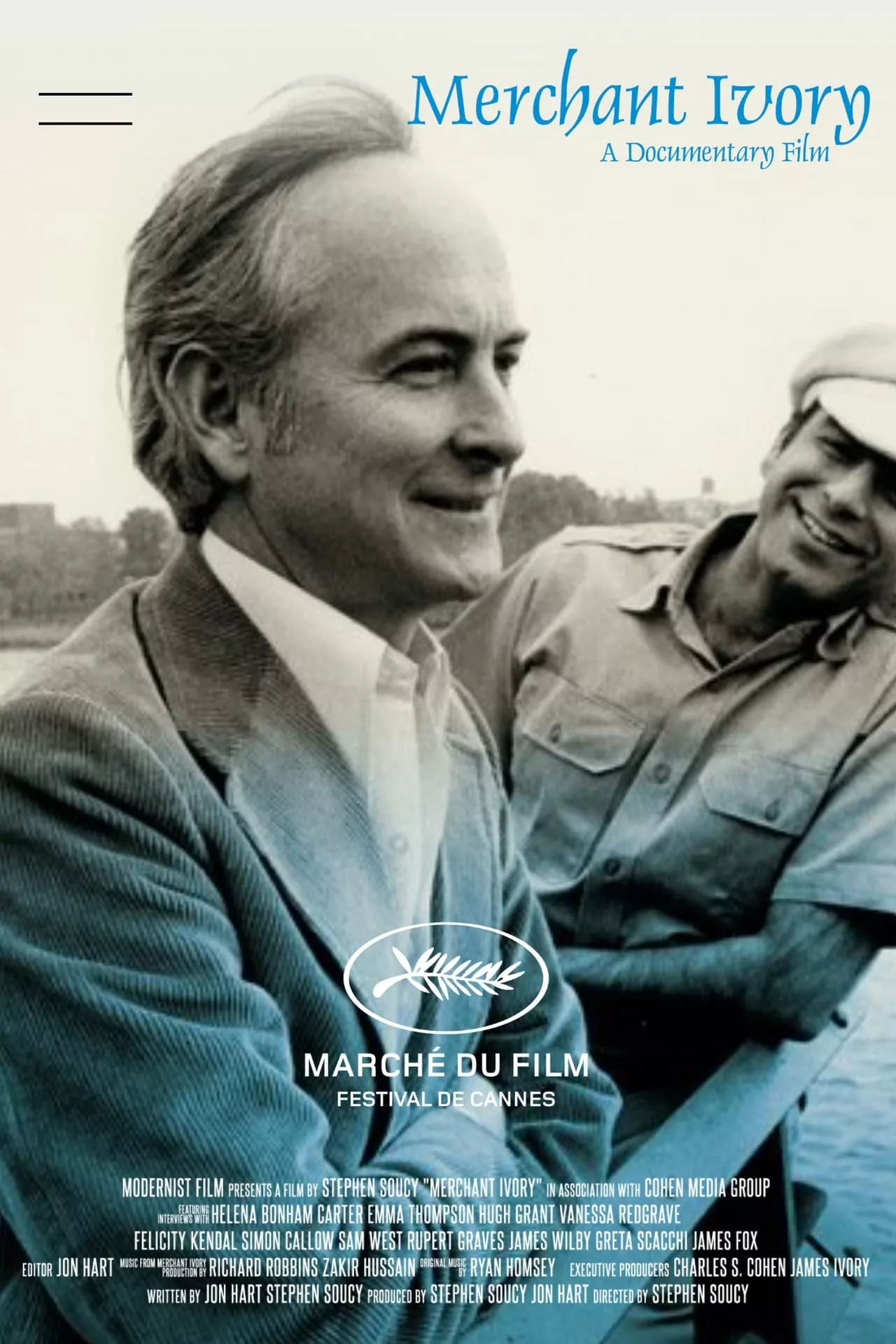

The best bits in the film are the snippets of actual behind-the-scenes footage (and still photos) from productions that show the dynamic between Ivory, seemingly a pretty cool, reactive chap, and Merchant, who’s more, shall we say, animated. It seems to be an immovable object-irresistible force kind of relationship, though obviously there were a lot of nuances. Merchant was the kind of producer who would constantly be urging people to work faster or try to save money on this or that. In the earlier days, he cooked all the meals himself to keep budgets down. There’s a priceless bit in one of the behind-the-scenes videos where Ivory wants to bring in a hair and makeup person before shooting inserts of an organist’s hands., and Merchant argues that there’s no reason to spend money on that if you’re only going to see the hands. For filmmakers specializing in portraits of elegance and repression, the phrase “down-and-dirty” fits better than you might expect, though of course that’s probably true of every production to some degree.