John Travolta became a movie star by playing a Brooklyn kid who wins a dance contest in “Saturday Night Fever” (1977). He revived his career by dancing with Uma Thurman in “Pulp Fiction” (1994). In “Be Cool,” Uma Thurman asks if he dances. “I’m from Brooklyn,” he says, and then they dance. So we get it: “Brooklyn” connects with “Fever,” Thurman connects with “Pulp.” That’s the easy part. The hard part is, what do we do with it?

“Be Cool” is a movie that knows it is a movie. It knows it is a sequel and contains disparaging references to sequels. All very cute at the screenplay stage, where everybody can sit around at story conferences and assume that a scene will work because the scene it refers to worked. But that’s the case only when the new scene is also good as itself, apart from what it refers to.

Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction” knew that Travolta won the disco contest in “Saturday Night Fever.” But Tarantino’s scene didn’t depend on that; it built from it. Travolta was graceful beyond compare in “Fever,” but in “Pulp Fiction” he’s dancing with a gangster’s wife on orders from the gangster, and part of the point of the scene is that both Travolta and Thurman look like they’re dancing not out of joy, but out of duty. So we remember “Fever” and then we forget it, because the new scene is working on its own.

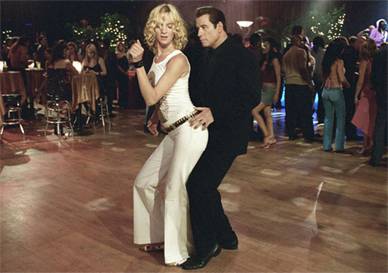

Now look at the dance scene in “Be Cool.” Travolta and Thurman dance in a perfectly competent way that is neither good nor bad. Emotionally they are neither happy or sad. The scene is not necessary to the story. The filmmakers have put them on the dance floor without a safety net. And so we watch them dancing and we think, yeah, “Saturday Night Fever” and “Pulp Fiction,” and when that thought has been exhausted, they’re still dancing.

The whole movie has the same problem. It is a sequel to “Get Shorty” (1995), which was based on a novel by Elmore Leonard just as this is based on a sequel to that novel. Travolta once again plays Chili Palmer, onetime Miami loan shark, who in the first novel traveled to Los Angeles to collect a debt from a movie producer, and ended up pitching him on a movie based on the story of why he was in the producer’s living room in the middle of the night threatening his life. This time Chili has moved into the music business, which is less convincing, because while Chili was plausibly a fan of the producer’s sleazy movies, he cannot be expected, 10 years down the road, to know or care much about music. Funnier if he had advanced to the front ranks of movie producers and was making a movie with A-list stars when his past catches up with him.

Instead, he tries to take over the contract of a singer named Linda Moon (Christina Milian), whose agent, Raji (Vince Vaughn), acts as if he is black. He is not black, and that’s the joke, I guess. But where do you go with it? Maybe by sinking him so deeply into dialect that he cannot make himself understood, and has to write notes. Raji has a bodyguard named Elliot Wilhelm, played by The Rock. I pause here long enough to note that Elliott Wilhelm is the name of a friend of mine who runs the Detroit Film Theater, and that Elmore Leonard undoubtedly knows this because he also lives in Detroit. It’s the kind of in-joke that doesn’t hurt a movie unless you happen to know Elliott Wilhelm, in which case you can think of nothing else every second The Rock is on the screen.

The deal with The Rock’s character is that he is manifestly gay, although he doesn’t seem to realize it. He makes dire threats against Chili Palmer, who disarms him with flattery, telling him in the middle of a confrontation that he has all the right elements to be a movie star. Just as the sleazy producer in “Get Shorty” saved his own life by listening to Chili’s pitch, now Chili saves his life by pitching The Rock.

There are other casting decisions that are intended to be hilarious. Sin LaSalle has a chief of staff played by Andre Benjamin (aka Andre 3000 of OutKast), who is a famous music type, although I did not know that and neither, in my opinion, would Chili. There is also a gag involving Steven Tyler turning up as himself.

“Be Cool” becomes a classic species of bore: a self-referential movie with no self to refer to. One character after another, one scene after another, one cute line of dialogue after another, refers to another movie, a similar character, a contrasting image, or whatever. The movie is like a bureaucrat who keeps sending you to another office.

It doesn’t take the in-joke satire to an additional level that might skew it funny. To have The Rock play a gay narcissist is not funny because all we can think about is that The Rock is not a gay narcissist. But if they had cast someone who was also not The Rock, but someone removed from The Rock at right angles, like Steve Buscemi or John Malkovich, then that might have worked, and The Rock could have played another character at right angles to himself — for example, the character played here by Harvey Keitel as your basic Harvey Keitel character. Think what The Rock could do with a Harvey Keitel character.

In other words, (1) come up with an actual story, and (2) if you must have satire and self-reference, rotate it 90 degrees off the horizontal instead of making it ground level. Also (3) go easy on the material that requires a familiarity with the earlier movie, as in the scenes with Danny DeVito, who can be the funniest man in a movie, but not when it has to be another movie than the one he is appearing in.