At night before she goes to sleep, Rosetta has this conversation with herself: “Your name is Rosetta. My name is Rosetta. You found a job. I found a job. You’ve got a friend. I’ve got a friend. You have a normal life. I have a normal life. You won’t fall in a rut. I won’t fall in a rut. Good night. Good night.” This is a young woman determined to find a job at all costs. She is escaping from the world of her alcoholic mother, a tramp who lives in a ramshackle trailer and runs away near the beginning of the story, leaving her daughter to fend for herself. Rosetta sees an abyss yawning beneath her and will go to any lengths to avoid it.

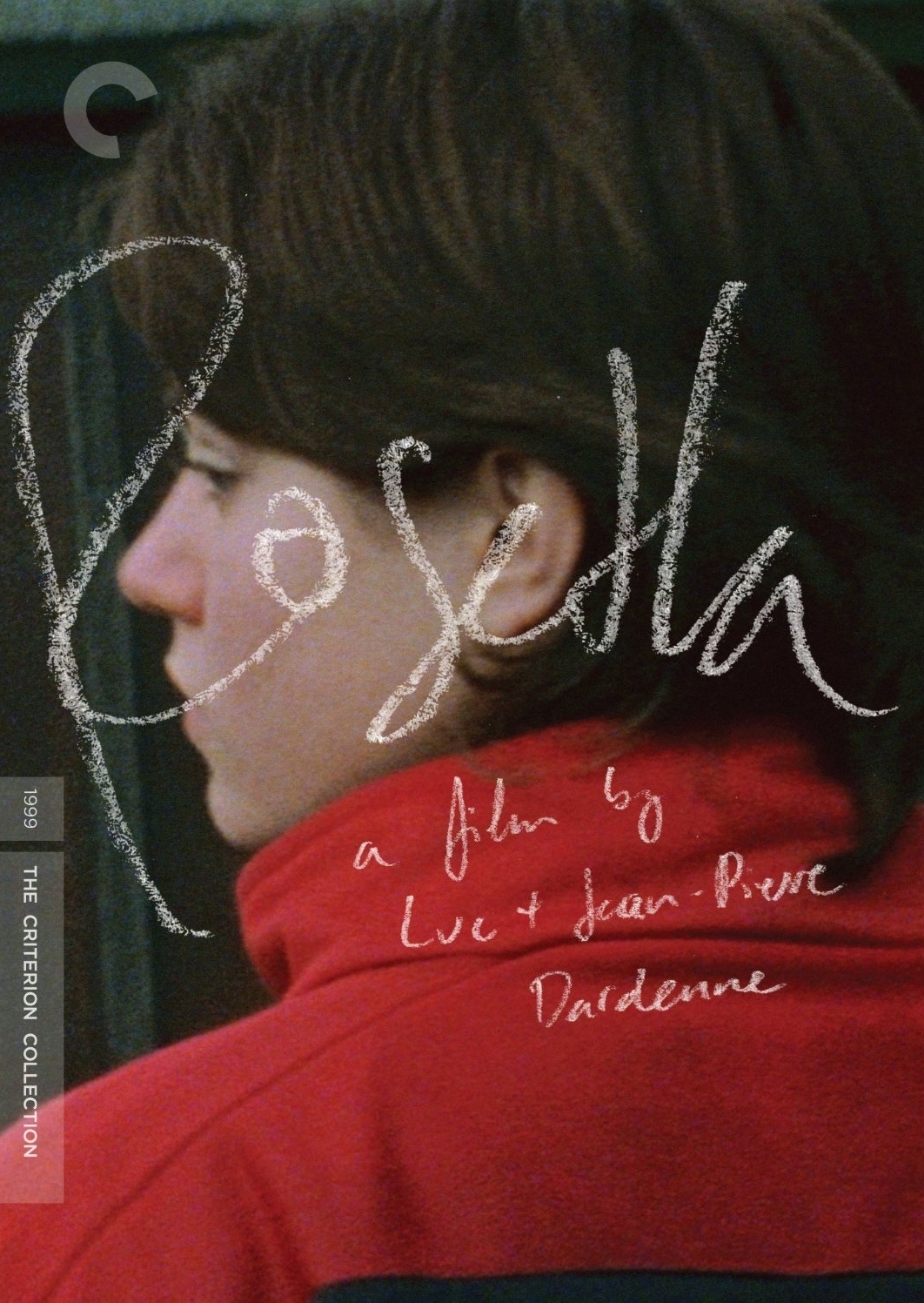

Her story is told in a film that astonishingly won the Palme d’Or at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival, as well as the best actress prize for its star, Emilie Dequenne. The wins were surprising not because this is a bad film (in its uncompromising way, it’s a very good one) but because films like this–neorealist, without pedigree, downbeat, stylistically straightforward–do not often win at Cannes. Variety’s grudgingly positive review categorized it as “an extremely small European art movie from Belgium.” Not just European but Belgian.

“Rosetta” opens with its heroine being fired, unjustly, we think, from a job. She smacks the boss, is chased by the police, returns home to her mother’s trailer, and we get glimpses of her life as she sells old clothes for money and sometimes buries things like a squirrel. She fishes in a filthy nearby stream–for food, not fun. She makes a friend of Riquet (Fabrizio Rongione), a kid about her age who has a job in a portable waffle stand (yes, Belgian waffles in a Belgian art movie). He likes her, is kind to her, and perhaps she likes him.

One vignette follows another. We discover that unlike almost every teenage girl in the world, she can’t dance. That she has stomach pains, maybe from an ulcer. One day Riquet falls in the river while trying to retrieve her fishing line, and she waits a strangely long time before helping him to get out. Later she confesses she didn’t want him out. If he had drowned, she could have gotten his job. After all, the local waffle king likes her, and she’d have had a job already, had it not gone to his idiot son.

What happens next, I will leave for you to discover. The film has an odd subterranean power. It doesn’t strive for our sympathy or make any effort to portray Rosetta as colorful, winning or sympathetic. It’s a film of economic determinism, the story of a young woman for whom employment equals happiness. Or so she thinks until she has employment and is no happier, perhaps because that is something she has simply never learned to be.

Two other films prowled like ghosts in my memory as I watched “Rosetta.” One was Robert Bresson’s “Mouchette” (1966), about a poor girl who is cruelly treated by a village. The other was Agnes Varda’s “Vagabond” (1986), about a young woman alone on the road, gradually descending from backpacker to homeless person. These characters are Rosetta’s spiritual sisters, sharing her proud disdain for society and her desperate need to be seen as part of it. She’ll find a job. She’ll get a friend. She’ll have a normal life. She won’t fall in a rut. Good night.