In the opening paragraph of his review of “Pola X,” the fourth film from acclaimed French director Leos Carax, Roger Ebert wrote “It takes a raving lunatic to know one. Not that I have ever met Leos Carax, the director of “Pola X,” so that I can say for sure he’s as tempestuous and impulsive as the subject of his film, but you aren’t described as an enfant terrible at the age of 39 without good reason.” Those words may have been written nearly 21 years ago but other than the fact that Carax is now 60, they are just as accurate now. One of the true madmen—in the best sense of the word—of today’s world movie scene, Carax has only made a handful of films but his rapturous and highly stylized visions, usually centered around intense romantic pairings that eventually go disastrously wrong, have made him into one of the few genuine cinematic poets working today. Carax is the kind of filmmaker who divides audiences between those who adore his distinct vision and those who think he is a pretentious lunatic, but leaves all viewers with the sensation that they’ve seen something they will not be forgetting anytime soon.

Such intensity does not come easily, of course, and although Carax has been directing since 1980, he has only made six feature films during that time with long gaps in between. As a result of this, any new Carax film becomes an event amongst cinephiles, and that is certainly the case with his latest work, the melodramatic musical “Annette,” his English-language debut. Originally scheduled to play at the scuttled 2020 Cannes Film Festival, it wound up serving as the Opening Night selection for this year’s iteration, an event that captured the attention of the world and which led to Carax wining the Best Director prize to boot. The year-long delay in its release would prove to have an additional benefit as well in that Carax’s key behind-the-scenes collaborators, Ron Mael and Russell Mael—a.k.a. the cult rock music duo Sparks—had their own profiles raised considerably thanks to the recent release of Edgar Wright’s acclaimed documentary about their lives and work.

Like any number of noted French filmmakers that preceded him, Carax—whose real name is Alex Christopher Dupont and whose professional name is an anagram of the names Alex and Oscar—got his start writing for Cahiers du cinema between 1979-80 (the most noteworthy being his defense of Sylvester Stallone’s often lambasted 1978 directorial debut “Paradise Alley”) and making a short film, “Strangulation Blues” (1980), before eventually moving on to his debut feature, “Boy Meets Girl,” at the age of 24 in 1984. In the movie, a young aspiring filmmaker named Alex (Denis Lavant, in the start of what would be a long and fruitful actor-director collaboration with Carax) has just learned that his girlfriend is dumping him for his best friend. He does not react to the news particularly well, to say the least. After wandering the streets in a tormented and potentially suicidal daze, he happens to meet Mireille (Mireille Perrier), first over an intercom and then later in person at a party where they have a long and odd conversation. It turns out that Mireille is also reeling from a bad recent breakup and the two find themselves on the same wavelength of need, albeit one that will inevitably end tragically.

Making its debut in the International Critics Week section of the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, “Boy Meets Girl” is easily the slightest of Carax’s features to date—like too many first films, you get the sense that it’s from a director more interested in showing off his creative influences (primarily Jean-Luc Godard, especially with the long monologue that Perrier delivers at one point) than in demonstrating a distinct artistic voice. And yet, the movie is still one of the most staggeringly self-assured directorial debuts to occur in French cinema at the time of its release, dwarfing even the more commercially successful initial offerings from Jean-Jacques Beineix (“Diva”) and Luc Besson (“Le Dernier Combat”), the two filmmakers to whom he would most often be linked. Utilizing black-and-white photography for his first and only time with the aid of cinematographer Jean-Yves Escoffier, practically every single shot of the film is gorgeous beyond belief (the most impressive, oddly enough, being a shot of, of all things, a pair of lovers on a bridge) and the performances from the two leads are both quite strong, especially Perrier. And while Carax’s grasp of simple human emotion may not be quite as strong here as it would become over time, he demonstrates a love and fascination with popular culture, primarily film and music (the soundtrack includes choice cuts from the likes of David Bowie, Serge Gainsbourg, and the Dead Kennedys), that strikes an undeniable chord that still rings strong today. In the end, the most important thing that “Boy Meets Girl” did was to serve as the kind of intriguing debut film that made you curious to see what its creator had in store for a follow-up.

That film would be “Mauvais Sang” (1986)—alternately known as “Bad Blood” and “The Night is Young”—a project that starts off as a sexy crime thriller with vaguely futuristic overtones before eventually shedding its genre skin for something more personal and passionate. Set in Paris in the not-too-distant future, the story revolves around STBO, a mysterious new sexually transmitted disease that is spread by and killing people who make love without any sort of emotional involvement—the affliction mostly affects the young and only one of the people having sex has to be doing it free of emotion for both to come down with it. A serum to serve as an antidote for STBO has apparently been developed but it has inexplicably been locked away so that those in need of it cannot access it. Two older criminals, Marc (Michel Piccoli) and Hans (Hans Meyer) are commissioned by a mysterious American woman (Carroll Brooks) into stealing it for her, and Marc then turns around and hires Alex (Levant again, though not the same character from “Boy Meets Girl”), a would-be gambler who is the son of a late former cohort, to assist in the crime. Things get very complicated when Alex, who has just broken up with his young girlfriend, Lise (Julie Delpy in an early role), meets Marc’s mistress, Anna (Juliette Binoche)—he naturally falls instantly in love with her but while she likes him enough, she still loves Marc. To further muddy things up, Lise is unwilling to give up Marc that easily and turns up on the day of the theft.

Once again, one can feel the influence of Godard—“Alphaville” immediately leaps to mind thanks to its vague sci-fi trappings—throughout, especially in the way that Carax presents viewers with the elements of a standard crime thriller: noble thieves, callow punks, daring heists, sexy dames, and the inevitable double-crosses. But Carax shows little interest here in making a typical genre exercise. The film is a vast improvement on “Boy Meets Girl” because while his visual style is just as captivating as before (most notably in a gorgeous sequence in which Alex, in a fit of what passes for joy for him, runs, jumps and dances over the course of several city blocks as David Bowie’s “Modern Love” plays on the radio), the drama feels as if it were generated from actual human experience, and not just from things gleaned from screenings at the Cinematheque Francais. Even if you watch it without knowing all of the various autobiographical elements at play—ranging from the long periods of silence that Carax used to undertake as a kid that are part of Alex’s character (inspiring the derisive nickname “Chatterbox”), to the fact that he and Binoche were dating at the time of its making—you get the feeling of a genuine beating heart just beneath the gorgeous surface elements, especially once Alex and Anna meet and the narrative takes on a more urgent focus that has little to do with the heist. Granted, the story’s concept of the faux-AIDS disease has not aged especially well but even that can be sort of forgiven—it feels more like the kind of conceit that a lovelorn high schooler might have come up with for a creative writing assignment out of innocence instead of cynicism. Although Carax would go on to make better films, “Mauvais Sang” is the one that showed that he was no mere un seul tour dans son sac and is probably the best entry point for newcomers to his oeuvre.

On paper, Carax’s third film, “Les Amants du Pont-Neuf” did not initially appear to be different from his earlier efforts—who could have possibly dreamed it would inspire a production that would live in infamy and make both the film and Carax into instant legends, both for good and for ill. Set primarily on and around the fames Parisian bridge name-checked in the title around the time of France’s Bicentennial celebration in 1989, the film charts the romance between Alex (Levant yet again), an alcoholic street performer who lives on the bridge along with older vagrant Hans (Klaus Michael Gruber), and Michelle (Binoche), a young artist from an upper-middle-class home who has chosen a life on the streets in response to a failed love affair and a seemingly incurable disease that is slowly destroying her eyesight. Hans objects to the presence of Michelle, ostensibly because he feels that the bridge is much too dangerous of a place for a woman, but she is there to stay, helping Alex with his performances and becoming more and more dependent on him as her eyesight gets progressively worse. Miraculously, a cure for Michelle’s illness is discovered and her family begins blanketing seemingly every available surface in the city with posters asking for information regarding her whereabouts. Fearing that Michelle will spurn him for good as soon as she regains her eyesight and money, Alex goes to increasingly desperate measures in his attempts to keep her in the dark about the cure and her family’s hunt for her.

In theory, it sounds like a simple enough story—the kind that could have formed the basis of one of the silent masterworks like “Sunrise” (1927) and “City Lights” that were presumably among Carax’s artistic influences. In fact, Carax originally intended it to a small, black-and-white film that was closer in its approach to the rawer “Boy Meets Girl” than the more elaborate “Mauvais Sang.” So how did it go from a relatively small-scale creation into one of the most expensive and extended productions in French cinema history? After Carax’s initial request to shoot the film on the actual Pont-Neuf bridge for a period of three months was deemed impractical by the mayor of Paris, the plan was to build a large but simplified model of the bridge in the town of Lansargues for the nighttime sequences and only shoot the daytime scenes on the actual bridge. But after getting permission to shoot on the bridge during a specific three-week period, filming was soon delayed when Levant injured himself on the set in a freak accident and could not work. Carax refused to cave to the pressures of insurers and recast Alex, and the decision was made to vastly upgrade the bridge set in order to make it suitable for daylight filming as well—in the end, it would be a virtual full-size recreation at its center and approximately 2/3rds scale on the sides. There would be additional setbacks—budget problems, a couple of extended production delays, and the dissolution of the romantic relationship between Carax and Binoche—and by the time it finally premiered in France in 1991, it had been in production for nearly three years.

In a way, it seems almost hellishly appropriate that the film, after all of the time and money spent on it, would be largely rejected by audiences when it opened. While audiences were perfectly content with enormously expensive historical dramas or super-sized epics from Hollywood, they evidently could not deal with so much money being spent on a film that was essentially a three-character drama at its core, combined elements of gritty reality (including a sequence early on set in a real homeless shelter) with elaborate stylistic touches and was, at its essence, a deeply personal narrative that would almost certainly never be accessible to mass audiences. While the film would prove to be Carax’s biggest success to date, its grosses did not come close to recovering the vast amounts spent on it and any hopes of additional earnings from the American market were dashed when a distribution deal could not be secured—American distributors were reportedly scared off both by the high price that the film’s producers were asking for, and the knowledge that Vincent Canby, the highly influential then-critic for the New York Times who saw it at a New York Film Festival screening, did not care for it. Eventually, Miramax picked up the distribution rights—presumably more because of Binoche, who had recently won an Oscar for “The English Patient”—and even though curiosity regarding the film had only grown in the interim, when it finally opened in America in 1999 as “The Lovers on the Bridge,” to describe what it received as a token release would be an insult to tokens.

Having read about Carax and his mad folly over the years and having been impressed with his previous films, I could not wait to finally see the film when it arrived. As high as my expectations were, it managed to exceed them. The movie, to put it succinctly, is nuts in the best possible way, the kind of grand romantic folly that few would ever dare to attempt and even fewer could possibly hope to pull off in the manner that Carax does. Blending together elements of neorealism and outright fantasy in ways that should not logically work to any extent, it is a meditation on romanic obsession, class conflict, and the hold that money has over virtually every aspect of life that is both epic in scale and startlingly intimate in its scope. The relationship between Levant and Binoche is beautifully portrayed, and it is legitimately heartbreaking to see Alex’s increasingly desperate efforts to prevent Michelle from leaving him and returning to her life of luxury (the most striking being a moment in which he sets fire to the posters asking for information on Michelle’s whereabouts that seem to cover every available inch of a long metro tunnel). From a visual standpoint, the film is never less than stunning—this is one of those movies that absolutely needs to be seen on the biggest of screens for its fullest impact—and the justifiably famous Bastille Day sequence, in which the two dance on the bridge and steal a police boat so that Michelle can water-ski beneath a massive fireworks display, is one of the great set-pieces of contemporary cinema.

After the rejection of his magnum opus, Carax wouldn’t return with a new film until the end of the decade. But anyone assuming he’d come up with something simpler and more audience-friendly must have taken a look at that follow-up, “Pola X” and determined that he had indeed gone mad. A modern-day adaptation of Herman Melville’s novel Pierre or, the Ambiguities (the title is inspired by an acronym of the book’s French title and the fact that Carax shot his tenth screenplay draft), it tells the story of Pierre (Guillaume Depardieu), a young man who seems to have it all—he lives with his widowed mother (Catherine Deneuve) in a lavish chateau in Normandy, he has just published a first novel under a pseudonym that is the talk of Paris, and is engaged to the seemingly perfect Lucie (Delphine Chuillot), who was the former love of his cousin, Thibault (Laurent Lucas). If that seems a little off—to say nothing of the unusually close relationship between Pierre and his mother—it’s nothing compared to what occurs when he finds himself being secretly pursued by an apparent vagrant woman (Yekaterina Golubeva). When he eventually confronts her, she reveals in a long monologue that she is his heretofore unknown half-sister Isabelle, the product of one of his father’s infidelities. Already feeling some kind of dissatisfaction with his seemingly comfortable life, this news inspires Pierre to essentially detonate his entire existence, abandoning everything to go to Paris with Isabelle. There, they find themselves crashing in a massive warehouse occupied by a shady terrorist organization and a constantly rehearsing orchestra consisting of synthesizers, steel drums, and iron bars played at ear-splitting levels. Amidst the chaos, Pierre and Isabelle become lovers and embark on a final streak of self-destruction that ends unhappily for all involved.

Melville’s original novel was his follow-up to his massive epic Moby Dick and scandalized readers with his breathlessly lurid ode to romantic obsession and artistic fervor. Bringing it to the screen in the wake of “Les Amants du Pont-Neuf,” Carax was clearly hoping for a similar reaction from audiences, and he got it. Using a deliberately abrasive and borderline feverish approach that proved to be an effective cinematic equivalent to Melville’s prose style and incest as a prevailing theme (in addition to what develops between Pierre and Isabelle, the relationship between Pierre and his mother is also one that is uncomfortably close), it often feels like Carax is challenging those who rejected his previous work with something that goes even further around the bend than that one even dared. And yet, even though the film is ostensibly one of his less personal efforts—it is based on material not originated by him and marks the first time that he worked without Denis Levant—it remains an uncommonly fascinating work. What it may lack in terms of eye-popping visual set pieces (though there is a haunting one involving Denueve racing off into the dark on a motorcycle), it more than makes up for in its sheer intensity, both in terms of the performances from Depardieu and Golubeva (which are especially touching when you consider that both would end up dying at relatively young ages) and in terms of the passion that Carax brings to the material. Although “Pola X” is a film that I love, I admit that it is nevertheless a hard one to recommend to actually recommend to others because it is so bleak and brutally oppressive at times. Still, fans of Carax and those willing to take a chance on decidedly outre forms of entertainment should check it out.

While the delayed release of “Les Amants du Pont-Neuf” in America meant that it would only be a short period of time before the arrival of “Pola X,” it would be more than 12 years until his next feature, a period in which he would direct music videos for Carla Bruni and New Order and contribute to “Tokyo!,” a triptych of Tokyo-based short films that also included segments directed by Michel Gondry and Bong Joon Ho. Carax’s short involves a strange man (Levant), known only as Monsieur Merde who emerges from the sewers to mildly terrorize the populace, all the while babbling in some unknown language, before eventually being captured and hauled into court in order to answer for his crimes. During this time, Carax apparently sought backing for an English-language film—including one potential project that would have apparently involved British supermodel Kate Moss—and finally decided to return to France and do something cheaper and simpler in order to reestablish his somewhat tattered commercial credibility.

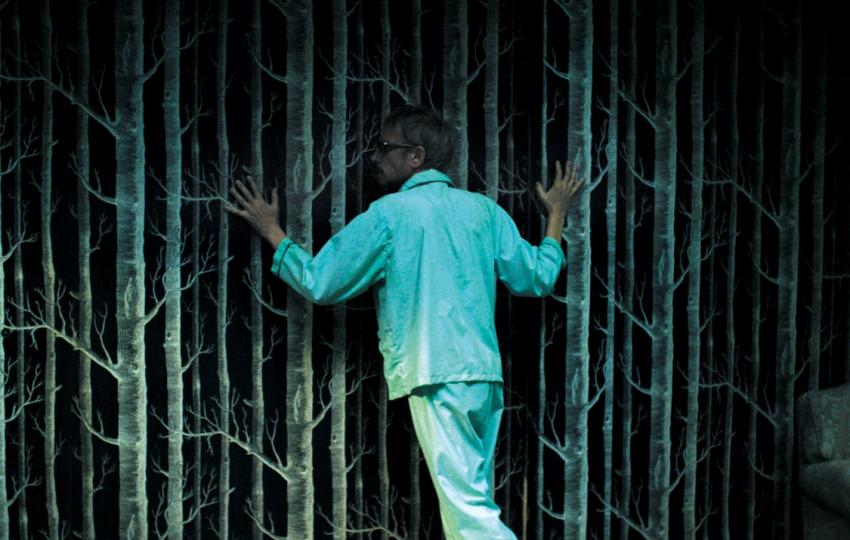

Inspired by the “Tokyo!” short, his next feature, “Holy Motors” (2012) would essentially be a series of vignettes, featuring Levant as a mysterious character known only as Mr. Oscar over the course of one long day. His job, so to speak, is to be driven in a white limousine (his driver is played by French screen legend Edith Scob) to a series of “appointments”—some vaguely defined, some less so—that he is to undertake with the aid of a seemingly endless supply of props and costumes. In one, he masquerades as an elderly female beggar. From there, he goes to a movie studio and performs a number of increasingly odd tasks while clad in a motion capture suit. In another, he adopts the guise of Monsieur Merde and arrives at the famed Pere Lachaise cemetery to break up a fashion shoot involving a model known, not insignificantly, as Kay M (Eva Mendes). As the day progresses, the tasks become alternately weirder, more violent and more personal. At no point is any of what he is doing explained, though it does conclude with one of the strangest moments Carax has ever captured on film, and that should say something.

Although Carax’s other films have not exactly been famous for their solid narrative structures, “Holy Motors” makes them seem practically staid by comparison thanks to its decidedly enigmatic approach. The film is so stuffed with ideas and bits of business—even transforming at the drop of a dime into a musical with a heart-rending performance from pop star Kylie Minogue as an old flame of Oscar’s—and is so determined to not explain any of them that the uninitiated may become simply exhausted with it all. Personally, I think it works wonderfully and am not bothered by the fact that none of what transpires is explained—is there a possible explanation for the sights on display here that would satisfy most viewers? Instead, I am more fascinated by the lush and always magnetic visual style provided by cinematographer Caroline Champetier (who was forced to shoot digitally as a way of lowering costs) and by the way that the film, despite essentially being a series of vignettes, still manages to feel like an organic whole, thanks to Carax’s magnificent control of the material and the amazing performance throughout by Levant. (The entire film could be interpreted as Carax’s tribute to his longtime collaborator.) Indeed, “Holy Motors” could be read as a meditation on the art of performance—Carax himself even gets into the act with a cameo performance at the very beginning—and a tribute to all the actors who have participated in his films over the years, even though their contributions have sometimes been overlooked by people focusing solely on Carax.

The films of Leos Carax are not for everybody and indeed, there’s a sense that his entire existence is some kind of elaborate joke based on the concept of a super-pretentious foreign filmmaker and his increasingly ludicrous offerings. And yet, for all of his wild excesses and controversies, Carax is as pure and beautiful and daring of a filmmaker as any; if you are one of those lucky souls who happen to be on his wavelength, watching his films can be a revelation that is almost overwhelming in its intensity. Barring some kind of miracle, his movies will never become blockbusters and, the Cannes prize notwithstanding, he will probably never receive all of the accolades he has long since deserved. That said, Carax has never seemed to be one interested in blockbusters or awards—you most likely won’t find him directing a new Marvel film (though the mind boggles at such a thought) or gunning for an Oscar. He’s more intent on directing the kind of films that affect viewers long after they have seen them, and long after more overtly successful movies have faded from memory. On that basis, both Carax and his filmography are stunning and unqualified successes.