Leos Carax’s “The Lovers on the Bridge” arrives trailing clouds of faded glory. It was already one of the most infamous productions in French history when it premiered at Cannes in 1992, where some were stunned by its greatness and more were simply stunned. Its American release was delayed, according to Carax, because its distributor vindictively jacked up the film’s asking price. Now it has arrived at last, a film both glorious and goofy, inspiring affection and exasperation in nearly equal measure.

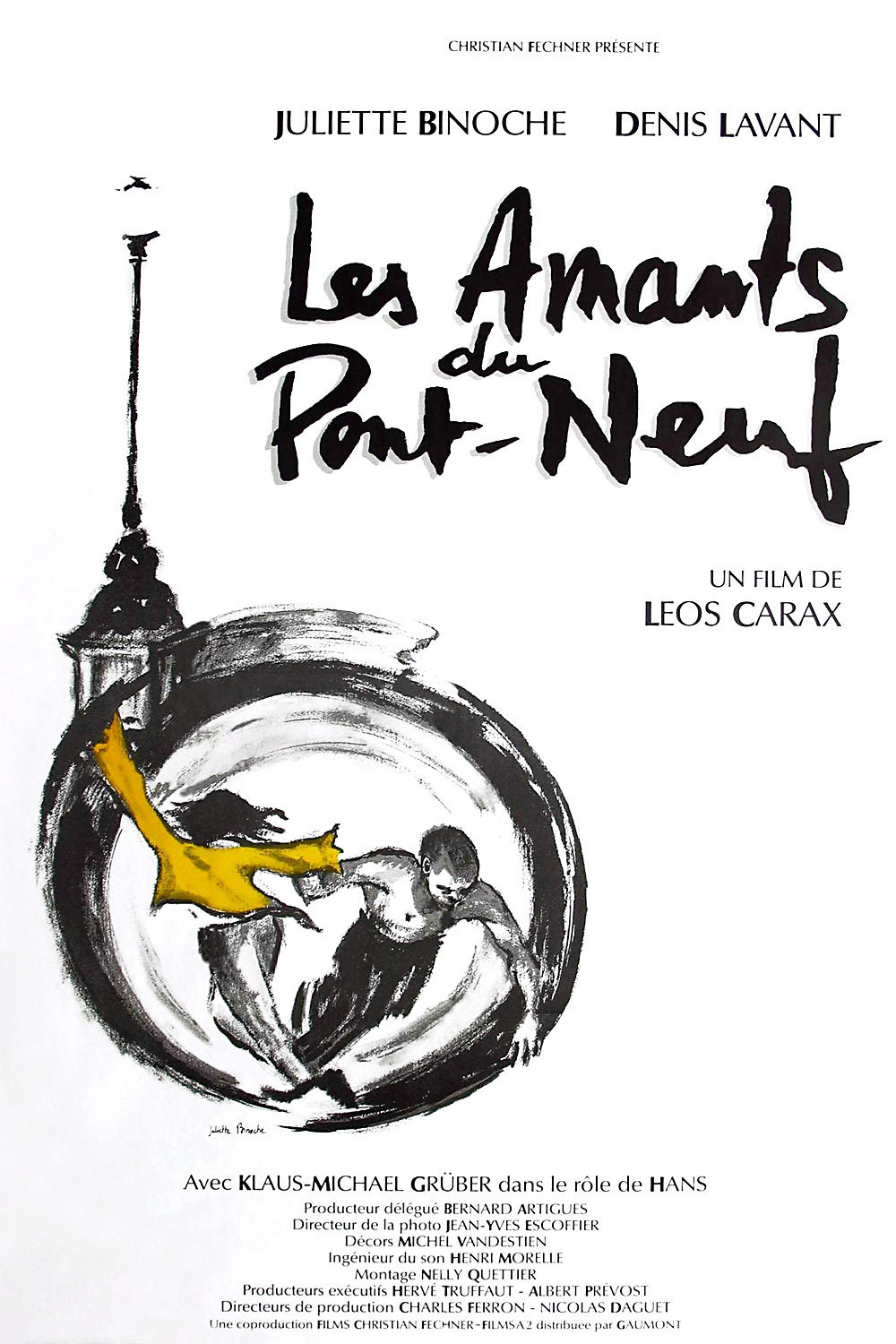

The story could have been told in a silent melodrama, or on the other half of a double bill with Jean Vigo’s great “L'Atalante” (1934), which was Carax’s inspiration. Carax’s film begins on the ancient Pont-Neuf, the oldest bridge in Paris, where two vagrants discover each other. One is Michele (Juliette Binoche), an artist who is going blind. The other is Alex (Denis Lavant), a drunk and druggie who supports himself by fire-breathing. The bridge has been closed for a year for repairs, bags of cement and paving blocks are tossed about, and they make it their home for the summer. Their landlord, so to speak, is a crusty old bum named Hans (Klaus-Michael Gruber).

This three-hander could have made a nice little film in other hands, but Carax’s production costs became legendary. His permission to shoot on the Pont-Neuf ran out while delays stalled his production; Lavant broke his leg, which held up the film a year, according to some sources, although since he uses a crutch and wears a cast in the film, one wonders why. (The broken leg is simply explained: Alex passes out in the middle of a boulevard late one night.) Thrown off the real bridge, Carax moved his entire production to the South of France and built a giant set of the Pont-Neuf, including the facades of three buildings of the famous Samaritaine department store. This was not cheap.

The lovers are both reckless and secretive. Michele, who wears a dressing over one eye, doesn’t reveal for a long time that she is going blind. Alex loves her and yet would rather read her mail and break into her former home than ask her flat-out about herself. Hans keeps trying to evict her from the bridge (“It’s all right for Alex, but not for a young girl like you”), but when he finally shares his own story, it opens the floodgates for all three.

There is much here that is cheerfully reckless, as when Alex does cartwheels on the bridge parapet above the Seine (did no authorities see him?). Or when the two of them steal a police speedboat so she can water-ski past the fireworks display on the night of the French bicentennial. Alex raises money by his fire-eating, his sweaty torso dancing in the middle of smoke and flames, and she pours drugs into the drinks of tourists to steal their money.

All well and good in a different kind of film. But other scenes break with the gritty reality and go for Chaplinesque bathos. Missing-person posters of Michele go up all over Paris– all over, on every Metro wall and construction site–and Alex sets them afire (why is there no one else in the Metro?). Then he torches the van of the man who is hanging the posters, and the man burns alive. This melodramatic excess leads, after a time, to a romantic conclusion that seems to dare us to laugh; Carax piles one development on top of another until it’s not a story, it’s an exercise in absurdity.

All of this is not without charm. Juliette Binoche, from “The English Patient,” Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Blue” and Louis Malle’s “Damage,” dares to play her character with the kind of broad strokes you’d find in a silent film, and old Klaus-Michael Gruber has a touching moment of confession as Hans. Denis Lavant is not a likable Alex, but then how could he be? His approach to romance is simple: He makes his most dramatic demonstration of love in her absence, by burning the posters so she will not leave him; when she’s there, he’s likely to be sullen, petulant or drunk. For two strong young people to embrace their lifestyle is itself an exercise in stylish defeatism; they have to choose to be miserable, and they do, wearing it well.

I felt a certain affection for “The Lovers on the Bridge.” It is not the masterpiece its defenders claim, nor is it the completely self-indulgent folly described by its critics. It has grand gestures and touching moments of truth, perched precariously on a foundation of horsefeathers.

So troubled was its distribution history that Carax waited seven years to make another film, which confirmed his unshakably goofy world view. That was “Pola X,” which opened the 1999 Cannes festival, and was a modern telling of Melville’s 19th century novel Pierre, about a young man’s idyllic relationship with his mother and his happy plans for marriage, all destroyed by the appearance of a strange dark woman who claims to be his father’s secret daughter. The movie “exists outside the categories of good and bad,” I wrote from Cannes; “it is a magnificent folly.” “The Lovers on the Bridge,” on the other hand, exists just inside the category of good. I am not sure, thinking about the two films, that I don’t prefer “Pola X.” If you have little taste or discipline as a filmmaker but great style and heedlessness, it may be more entertaining to go for broke than to fake a control you don’t possess.