We know he lives in movies because we literally find him in one. Leos Carax’s much-debated “Holy Motors” begins with a man (Carax himself) asleep in bed, then waking and approaching a wall of the room that looks like a forest. Knowing just where to look among the trees, he unlocks a door using a key growing from his finger. Well, isn’t that what artists do? Unlock doors with their fingers?

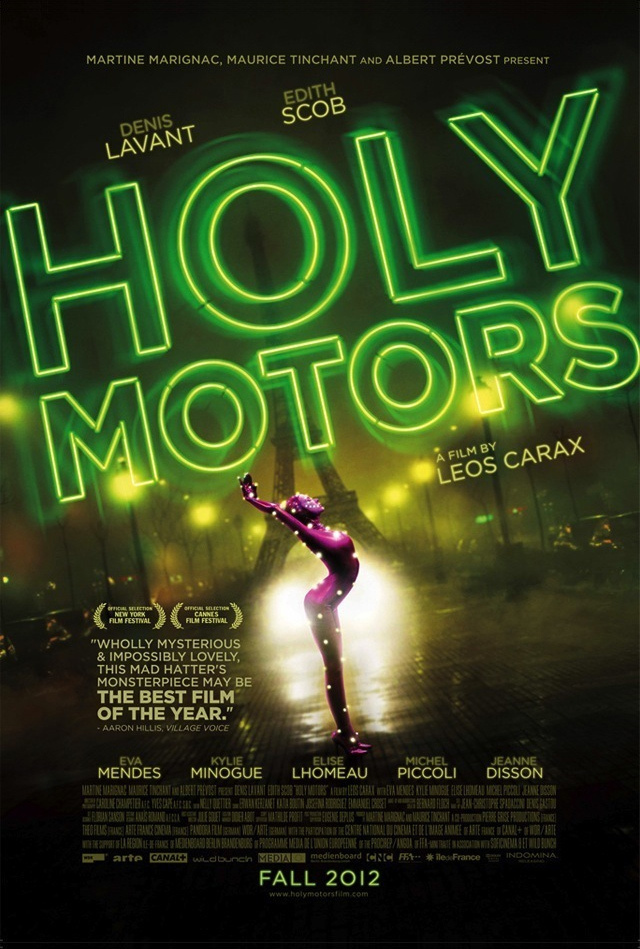

Now this man is inside a cinema, and we meet Monsieur Oscar (Denis Lavant), who lives in a house that seems designed by the same architect employed in Jacques Tati’s “Mon Oncle.” He gets into the waiting limo, driven by a taciturn woman, and we see that the back of the limo, seemingly much larger inside than the outside, is a dressing room filled with costumes and props. When he gets out the first time, he has transformed himself into a wretched beggar woman. This will be the first of his many roles, or assignments, or embodiments. He performs in bizarre and mysterious ways, linked only by the desire of a mime or comedian to entertain and amaze us. His “appointments” take him into personas so diverse, it would be futile to try to link them, or find a thread of narrative or symbolism. If there is a message here, Walt Whitman once put it into words: “I am large. I contain multitudes.”

Here is M. Oscar as a madman wandering street markets and eating flowers or whatever else he can snatch up. M. Oscar in the most famous cemetery in Paris, Pere Lachaise, occupied by the dead and famous (Moliere, Chopin, Jim Morrison, Colette, Oscar Wilde). In “Holy Motors,” however, the cemetery’s tombstones carry no names, requesting us, to “visit my web site.”

Here is M. Oscar transforming a fashion model (Eva Mendes) into a Muslim woman concealed within her costume. And that’s not all that happens to her, although she adheres to the model’s code and never betrays emotions or opinions. Her job is to embody a beautiful object for the purposes of others. Their travels through the city lead to the roof of the Samaritaine department store, producing stunning vistas of Paris.

Celine (Edith Scob), his reserved chauffeur, seems long accustomed to her role. Once she expresses concern that M. Oscar hasn’t eaten all day. Their day began at dawn and lasts far into the night, one “appointment” after another.

This has been a year of leading roles for limousines. M. Oscar’s car upstages the limousine in David Cronenberg’s “Cosmopolis,” and the journeys of both cars seem to be odysseys through their cities, for purposes not very clear to the audience. “Holy Motors” is the more entertaining and funny of the two, although some parts are not funny at all, and many laughs are of disbelief or incredulity. Both end with their limousines going home for the night, answering a question asked in “Cosmopolis,” although when the limo in “Holy Motors” gets home, its day is far from over.

Here is a film that is exasperating, frustrating, anarchic and in a constant state of renewal. It’s not tame. Some audience members are going to grow very restless. My notion is, few will be bored.