And he’ll be producing Rep. Joe Wilson’s next heckle

He thought it was another sketch. Somebody should have dropped a Brüno on his head…

(tip: Daniel Johnson)

He thought it was another sketch. Somebody should have dropped a Brüno on his head…

(tip: Daniel Johnson)

“I don’t think you go to a play to forget, or to a movie to be distracted. I think life generally is a distraction and that going to a movie is a way to get back, not go away.”

— writer/director/actor Tom Noonan (see epigraphs at right)

The whole reason I keep at this blog is because it gives me the freedom to write about whatever I want and not have to write about anything I don’t. And it lets me communicate with Viewers Like You. After many years on what we used to call the “review treadmill” of unidirectional daily and weekly newspaper movie reviewing (with tight deadlines and/or tight space restrictions), this is a luxurious change of pace for me. I can freely obsess over minutiae in obscure (or mainstream) films, new and old, if it strikes my fancy. And I have the liberty to virtually ignore things I don’t care about that are being obsessively covered elsewhere (“Twilight,” Lindsay Lohan’s jail time, Harry Potter, Comic-Con, Oscars, box-office). Then again, if some pop-culture phenomenon piques my curiosity (say, a new movie by James Cameron or Christopher Nolan, or The Return of 3-D), I may just find myself compelled to say something about it. Then we can examine it, look at it from different angles, and bandy it about.

But in the more than five years since I started writing Scanners as a separate editorial offshoot (an annex, really) of RogerEbert.com, I’ve never sought to give equal coverage to all kinds of motion pictures. This is a blog about looking critically at movies — based on my ideas of film criticism (of which I have many after doing it for so long) and my kinds of movies, and positive and negative examples that serve to illuminate both. That’s all.

View image Shot #1 (of this clip — not of the entire sequence). A fairly conventional shot establishing the red car on the left gaining on the orange one on the right. I’d say these shots look a lot cooler on the page (and probably on the computer storyboards) than they do in “action.”

View image Shot #2. Red car driver (Taejo) pulls up alongside Snake Oiler (not that their identities are clear from the movie itself).

View image Shot #3. Back to two-shot.

There’s no action

No no no there’s no action

— Elvis Costello, 1978

When I was four years old I went to the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair — the one where Elvis and Joan O’Brien were, according to the ads, seen “swinging higher than the Space Needle” in “It Happened at the World’s Fair” (Norman Taurog, 1963). There was a roller coaster called the Wild Mouse, but I was too afraid to ride on it. I did, however, like The Scrambler, which whirled you around in a logical geometrical pattern (although it felt pretty wild when you were on it) that looked really cool when seen from directly overhead, up on the observation deck of the Space Needle. (For years I had nightmares about falling off of the Needle, and if I’d ever hit the ground I would like to think I would have been extra-scrambled by the Scrambler.)

The prow of the ferry in the first couple shots of Roman Polanski’s “The Ghost Writer” isn’t like any I’ve seen before. It raises up, like the visor on the headpiece of a suit of armor (or the crusher arm on a garbage truck), to let the cars on and off. It’s just a little bit… odd, the sort of detail you’d expect Polanski would include — not necessarily unsettling on its own but somehow menacing when seen through the lens of Roman Polanski. Moments later, the vehicles begin to disembark, with the exception of a car in near the front of the center lane that blocks traffic, creates a nuisance, and imparts dread. There’s nobody in it. So, where did the driver go?

A few scenes later, a private plane lands at a small airport and we’re given a shot of the fuselage framed around the (closed) door on the left and the first two windows on the right. Cut to a reverse angle of people waiting on the tarmac, and then back to the same basic configuration. The door pops open and it’s one of those kind with the hinge on the bottom that folds down into a little set of stairs. The motion of the mechanism visually echoes the prow of the ferry. But there’s something else in this shot that will come back to haunt us: the company name Hatherton, meant to recall Halliburton. It’s just there, and it pops up in other shots throughout the movie, but it doesn’t quite click into place until a Google search that hyperlinks pieces of various characters’ pasts late in the film.

Last spring I was on a panel at the Conference on World Affairs in Boulder, CO, called “Why We Still Go to the Movies.” The first thing I said (because it was the first thing I thought of) was: “Permission to stare.” I wasn’t thinking about any particular movie (the title said “the movies”) or about the business or anything like that. I was trying to get at the essential appeal of the movie-watching experience. And, for me, that has always been about looking really closely, and paying rapt attention to what is on view. Remember how your mom always said it wasn’t polite to stare? Well, it’s just the opposite at the movies.

(Actually, I guess it’s not technically staring because my eyes tend to be constantly looking all around the frame to see what’s going on, not just fixing on one particular thing. Unless it’s a creature of spectacular beauty.)

You can call it voyeurism (because that’s also what it is), but it’s a special kind of staged, mediated voyeurism. Even when I was a little tyke and my parents would take me to Disney movies like “Pinocchio” and “Bambi” and “Mary Poppins,” I of course wanted to lose myself in a Magical World of Entertainment, but I also liked that nobody in there could see me, and that I would be allowed to vicariously experience and study behaviors, situations and emotions that I might encounter in real life, too. Later, I felt the same way about watching Godard and Truffaut and Altman and Welles and Mizoguchi and Ozu and… (And even later I’d find out that was also part of a classic child of alcoholic behavior — an obsession with trying to figure out what “normal” is and knowing you aren’t it.)

Nobody has ever satisfactorily explained what is supposedly “ambiguous” about the ending of “No Country for Old Men,” which has one of the most exquisitely judged denouements in movie history. (“A Serious Man,” too.) So, what is it, precisely, that some folks need explained or resolved for them? The smartly funny video above imagines what would happen if “The Wrestler,” “Lost in Translation,” “NCFOM,” “The Graduate” and “The Sopranos” gave the literal-minded exactly what they desire.

This seven-minute 2008 propaganda film from the Iranian Intelligence Ministry (Ahmadinejad regime), begins with a White House conspiracy involving an animated Senator John McCain (aka Mr. Bomb Bomb Bomb, Bomb-Bomb Iran) and George Soros. It’s kind of hard to tell who is who, but isn’t it remarkable to see them cooperating at all? They discuss a plan to “contact authors, intellectuals, and influential people in society who have common interests with us” — as well as “NGO’s that share our goals” — to expand on the mind-altering efforts used at international scientific conferences and harness the power of satellite TV to bombard the Iranian people with “regime change” propaganda.

The second part is a live-action espionage Afterschool Special about a young man who falls in with a bad crowd who conspire through such subversive technologies as e-mail to “pass on the instructions we get from satellite TV” and please their “friends in America.” (The internal use of Twitter and Facebook were apparently not perceived as significant threats to the government at the time.)

The worst thing the U.S. could do right now is to feed Ahmadinejad’s disinformation machine by lending credence to the government’s claims that the protesters are not citizens with legitimate complaints but American tools with hidden agendas.

(tip: The Plank)

UPDATE below…

Poster image for “The Host.”

From today’s Seattle Post-Intelligencer, a story that echoes the scandalous real-life inspiration for the Korean monster movie, “The Host,” which opens in various US markets tomorrow (March 9, 2007):

When Daniel R. Storm, a University of Washington professor whose work includes studying the brain, found out that getting rid of potentially dangerous chemicals in his lab would cost $15,000, he decided to find a cheaper way.

Storm, a professor in the Department of Pharmacology, dumped ethyl ether down the sink.

On Wednesday, Storm, 62, pleaded guilty in federal court in Seattle to pouring the ethyl ether, which can explode or catch fire if handled improperly, down the laboratory sink in June 2006. Prosecutors say Storm then tried to cover up his actions.

He could face up to five years in prison and a fine of $250,000 for knowingly disposing of a hazardous waste without a permit. But prosecutors are recommending probation, said Emily Langlie, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Seattle.

When the UW’s Environmental Health and Safety Department told Storm that it would cost $15,000 to dispose of the solvent, he broke three metal containers with an ax and poured the liquid down the sink in his lab. He also disposed of an ethyl ether and water mixture in two glass bottles.

Storm then poured water and an ethanol solution down the drain to dilute the solvent, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

He admitted that he did not want to pay for the disposal from his laboratory account. The liquid was not used in his research, but was found in his lab.

Believe me, I will let you know if a giant, fire-breathing monster (or something worse) emerges from beneath the waters of Lake Washington, Lake Union or Puget Sound in about 2011 or so.

And from an editorial in the 2000 Korea Times regarding the similar precipitating incident that begins Bong Joon-ho’s “The Host” — South Korea’s most popular movie:

“Would they dump toxic chemicals into the Potomac River?” This is the caption of an editorial by Korea’s largest circulation daily on the shocking news that the U.S. Forces Korea admitted to dumping formaldehyde and methanol into the Han River through the drainage system at its Yongsan military base in Seoul. These toxic chemicals are widely known to cause cancer and birth defects.

The Han River supplies drinking water for over 10 million citizens residing in metropolitan Seoul and its satellite cities. Are Koreans disposable people? The materials in question were embalming fluids.

The news is ethically repulsive. Environmentally, the act is destruction-friendly. In psychiatric terms, it comes close to an act of quasi-murder. For, what matters here is the sick mind and attitude that made possible the dumping of the cancer-causing substance. Whether or not the quantity of the discarded, amount was enough to cause cancer is not the issue here. The USFK’s clarification that it at one time dumped up to 20 gallons (75.7 liters) of formaldehyde in no way alters the ethical insanity of the people involved.

In “The Host,” the toxic effect of that “ethical insanity” becomes — quite literally — monstrous. And in answer to the question posed at the beginning of the editorial: Of course “they” would dump toxic chemicals into the Potomac if it was cheaper and they thought they could get away with it. I have no doubt some of “them” are doing it right now. Many corporations and governments do not feel it’s their responsibility to deal with the toxic biproducts they produce because it’s not a revenue-generating activity, and their responsibility is to save (and make) money. They are beholden only to their owners, stockholders and/or campaign contributors.

If the public has to pay the occasional price (death, cancer, etc.), that’s their fault for drinking the wrong water or breathing the wrong air. The price of cleaning up and disposing of these toxins might hurt these corporations’ ability to compete in a free marketplace, and that would result in job cuts and declining stock prices. (Providing health insurance for people who develop these pre-existing conditions would be bad for insurance companies, too.) And all this might hurt the economy in the short-term, whereas releasing poisons into the great big outdoors probably won’t manifest any noticeable effects for years — long after the government has changed or the company has merged with some larger conglomerate, and then it’s someone else’s problem.

Hey, just look at Dick Cheney: When he was at Halliburton in 1998, he arranged the purchase of Dressler Industries. But –oops! — it turned out Dressler had a host of asbestos-lawsuit liabilities. Enough to threaten Halliburton’s existence. So, Halliburton had Dressler and other subsidiaries declare bankruptcy in order to limit their “exposure.”

From a 2005 column by Allan Sloan in the Washington Post:

While Halliburton’s all-stock takeover of Dresser was valued at $7.7 billion when it was announced in February 1998, it was worth only $5.3 billion when it was completed seven months later. The bankruptcy settlement is costing Halliburton just about that much: around $2.8 billion in cash, Halliburton stock with a market value of $2.3 billion the day before Dresser’s bankruptcy was resolved and miscellaneous odds and ends and potential payments.

The bankruptcy resolution, which became final on Jan. 3, covered both the Dresser problems and the smaller asbestos problems that Halliburton already had. […]

I give Halliburton’s current management huge credit for pulling off this tricky maneuver. And I give them big credit for dealing with the problem rather than awaiting a miracle rescue from Congress. Almost from the day it took office, the Bush administration has pushed hard to get Congress to limit asbestos liability. That includes President Bush’s visit to Illinois last week to push his “reform” proposals.

Halliburton, whose fortunes are tied to the oil industry, has profited from the surge in oil prices. Even though its stock has quadrupled from its asbestos-woe low, it’s still below what it was when Cheney left in the summer of 2000. Imagine what Halliburton shares would fetch today had the Dresser problems never happened. Much more than it currently sells for, I’m sure.

A Cheney spokesman said the vice president wouldn’t comment about Halliburton, and referred all queries to the company.

No doubt Cheney feels bad about leaving Halliburton with such a mess. Perhaps someday he can do something to make it up to them.

Fight Flub: America’s approach to the fundamentally misconceived “War on Terrorism” thus far…

“It’s now fundamentally an information fight. The enemy gets that, and we don’t yet get that, and I think that’s why we’re losing.”

— David Kilcullen

In “Knowing the Enemy,” an essential article in the December 18 issue of The New Yorker, George Packer reports that some experts inside the Pentagon and Departments of State and Defense have been trying for years to explain (to Condoleeza Rice and others) why the US has yet to properly identify the enemies it’s fighting in the “War on Terrorism” — and, therefore, why we have been so shockingly ineffective at fighting it. As David Kilcullen, an Australian lieutenant colonel and political anthropologist currently “on loan” to the State Depatment, explains: “After 9/11, when a lot of people were saying, ‘The problem is Islam,’ I was thinking, It’s something deeper than that. It’s about human social networks and the way that they operate…. [I]t’s not about theology. There are elements in human psychological and social makeup that drive what’s happening. The Islamic bit is secondary. This is human behavior in an Islamic setting. This is not ‘Islamic behavior.’”

Packer reports:

In a lecture that Kilcullen teaches on counterterrorism at Johns Hopkins, his students watch “Fight Club” the 1999 satire about anti-capitalist terrorists, to see a radical ideology without an Islamic face.That, I submit, is revelatory. I wonder if those who can’t see what’s going on in “Fight Club” — the feelings of impotence and alienation and personal violation that fuel the rage and the desire to belong to a force larger than the individual, even if it’s just a form of nihilistic fascism that lacks the religious, racial or nationalistic aspirations of Naziism, Soviet Communism or “Bin Laden-ism” (for lack of a better term) — can even begin to comprehend contemporary jihadism and what we now call “the insurgency” (as if there were just one).

Just as the Bush administration misunderstood Saddam’s motives (Why is he acting like he’s hiding something? Is it because he’s hiding WMD — or because he knows he’d be gone in a second if anybody knew he didn’t have them?), they have also misread the nature of Osama bin Laden’s motives, power and strategy for Al Quaeda and global jihad:

Just before the 2004 American elections, Kilcullen was doing intelligence work for the Australian government, sifting through Osama bin Laden’s public statements, including transcripts of a video that offered a list of grievances against America: Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, global warming. The last item brought Kilcullen up short. “I thought, Hang on! What kind of jihadist are you?” he recalled. The odd inclusion of environmentalist rhetoric, he said, made clear that “this wasn’t a list of genuine grievances. This was an Al Qaeda information strategy. Ron Suskind, in his book “The One Percent Doctrine claims that analysts at the C.I.A. watched a similar video, released in 2004, and concluded that “bin Laden’s message was clearly designed to assist the President’s reëlection.” Bin Laden shrewdly created an implicit association between Al Qaeda and the Democratic Party, for he had come to feel that Bush’s strategy in the war on terror was sustaining his own global importance. Indeed, in the years after September 11th Al Qaeda’s core leadership had become a propaganda hub. “If bin Laden didn’t have access to global media, satellite communications, and the Internet, he’d just be a cranky guy in a cave,��? Kilcullen said.Kilcullen would make a good film critic. He understands human nature and has an eye for reading it in dramatic context. Thumbs up for him! (Bin Laden hadn’t been a champion for the Palestinian cause before, either. It was obvious he was trying to create the perception of a war declared by the West against Muslims — and Cheney, Rummy and Co. played right into that perception from Day One.)

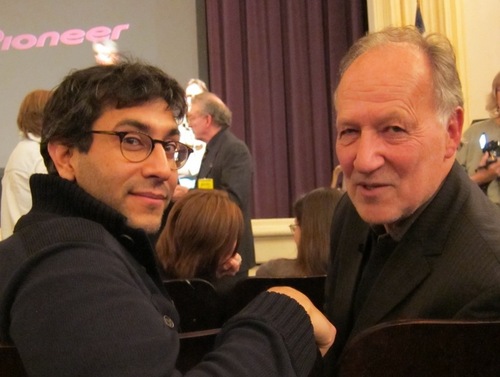

… to write anything last week at CWA where there’s hardly a moment to breathe (gasping at the mile-high altitude aside) between panels, conversations, lunches, parties, receptions (and — for me, anyway — precious sleep). You have to understand: I often go days without actually seeing or speaking to anybody; all this socializing is exhausting for me. I’ll be looking back at the experience this week, but in the meantime, in case you missed it, Roger Ebert writes about the first day’s Cinema Interruptus with Werner Herzog, Ramin Bahrani and “Aguirre, the Wrath of God.”

(Above: Photo by Roger Ebert. And aren’t Ramin’s new frames terrific?)

Edward Yang in 2001. (AP photo)

Director Edward Yang, perhaps most familiar to US audiences for his 2000 epic “Yi Yi” (which won him Best Director honors at the Cannes Film Festival), died Friday at age 59, another victim of colon cancer. The Shanghai-born, Taipei-raised filmmaker died in Beverly Hills.

In the latest issue of cinema scope, Jonathan Rosenbaum writes:

For $17 you can acquire Edward Yang’s greatest film, “A Brighter Summer Day” (1991) with English subtitles from www.asiafilm.com. On the back of my copy, one can read, “This masterpiece film is not currently being distributed in any video format worldwide, so we are making this available as a service to film lovers. If you know how we can contact Edward Yang to try to distribute BSD on DVD in North America, please contact us at (940) 497-FILM. Thank you and enjoy!” The only problem with all this is that this one-disc edition is perversely subdivided into only two chapters while the $15, two-disc version available from www.superhappyfun.com, also subtitled, has more normal chapter divisions. (The four-disc English-subtitled VCD version, which has no chapter breaks at all, no longer appears to be available.) Also, the asiafilm version is 228 minutes long, whereas IMDb rightly or wrongly lists the film’s original running time as 237 minutes. I can’t vouch for the running time of the two-disc version, except to point out that it starts and ends in the same way as the asiafilm version. (The inferior three-hour version, which Yang was originally talked into editing in order to get the film released in any form, appears to have vanished, like the two-hour version of Jacques Rivette’s “L’amour fou” [1969]; I say good riddance)”Yi-Yi” is available in a Criterion Collection DVD edition.

David Bordwell sums up the terrible news from the totalitarian state of Iran about the outrageous sentence given to director Jafar Panahi (“The White Balloon,” “The Circle,” “Offside,” etc.) after he was accused of conspiring to make an “anti-regime” film:

From Tehran comes the shocking news that Jafar Panahi, one of the finest of Iranian filmmakers, has been sentenced to six years in prison. The sentence also bans him from filmmaking for twenty years, forbids him to leave the country, and forbids him from giving interviews to the press, foreign or domestic. Panahi’s collaborator Muhammad Rasoulof was also sentenced to six years in jail. […]

The charges may be simply a pretext for silencing a prominent figure critical of current Iranian society. Panahi’s films do not circulate legally there, and he is widely believed to be in sympathy with liberal forces. The government has sought to eradicate the most visible of these factions, the Green Party. Even Islamic clerics have been swept up in the crackdown. A parallel case to Panahi’s is the attack on Mohammad Taqi Khalaji, a dissident cleric. Last January he was arrested and his computer and papers were seized. He too was incarcerated in Evin prison before being released on bail. Yet he was not formally charged with anything. His personal papers, including his passport, were not returned to him.

You can get some grim satisfaction for knowing that movies still matter in some parts of the world. Films have the power to shock bureaucrats and threaten authoritarian regimes. Instead of being simply “assets” or “content” to be extruded across platforms and shoved through release windows, cinema is in some places taken seriously as political critique.

Between Two Ferns with Zach Galifianakis from Between Two Ferns

Enlarge image: Sweeeeeeeet slow-mooooootion.

From Mike Leto, Bethpage, NY:

I agree with you about how opening shots are one of the most important parts in a film. If the opening shot is good then the movie takes hold of me right from the beginning and that can lead to a great movie. I’m glad I saw “Boogie Nights” and “Barry Lyndon” on your list and you made me look back on “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” to make me see how important that opening shot really is. But if I were you, I would need these three great opening shots on my list:

“Aguirre, The Wrath of God” — The first shot sets up the mood for this film perfectly. First, the opening titles tell us that this is a doomed mission but we didn’t even need message. We cut to a mountain covered in fog but as the fog starts to drift away we see a long line of men walking down the side of the mountain. This image, along with the music, sets a tone of failure and desparation before things actually start to go wrong.”Dazed and Confused” — I know what you’re thinking but I happen to think that this film is a masterpiece and the first shot (just like “Aguirre”) sets the perfect mood. When you hear Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion” and you see the car making the turn in slow motion it brings us back in time. Not to 1976. But to our teenage years. We don’t have to worry because it brings us back to a time in our lives where the worst thing that happens is that the party got cancelled.

Or: Once is not enough?

“They love it, they don’t like it, they like it better a second time, they see it a third time and they reverse their opinion.”

— Paul Thomas Anderson on “The Master,” in a Toronto Star interview with Peter Howell

The critics agree! Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film “The Master” is… ambiguous. What they don’t agree on is whether, as we say in the software world, that’s a bug or a feature. Is the movie “demanding” and artfully elusive, challenging audiences by refusing to offer a conventional dramatic catharsis or provide an artificially wrapped-up ending; or is the thing just vague, opaque, muddled? The answer depends on who you ask, what they think of Anderson as a filmmaker and, possibly, what they expected going in: a historical exposé of Scientology, a portrait of post-war/micd-century America, “character study,” an acting duel… Take a look:

Here’s a prime example of the kind of cross-pollination on the Internet (and between blogs most of all) that I find so exciting and rewarding. I first learned from Andy Horbal at the movie blog No More Marriages! that Rob at A Film Odyssey had started a discussion about Extended Takes, inspired in part by the ever-ongoing Opening Shots Project here at Scanners. I think I first heard about Andy’s blog from girish, or possibly Dennis at Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule, through whom I also discovered such diverse movie-obsession sites as Zach Campbell’s Elusive Lucidity,” Aquarello’s Strictly Film School, Filmbrain’s Like Anna Karina’s Sweater, That Little Round-Headed Boy, Eric Henderson’s when canses were classeled…, Tom Sutpen’s If Charlie Parker Was a gunslinger… and many others, some of which you will find listed in the right hand column down the side of this blog.

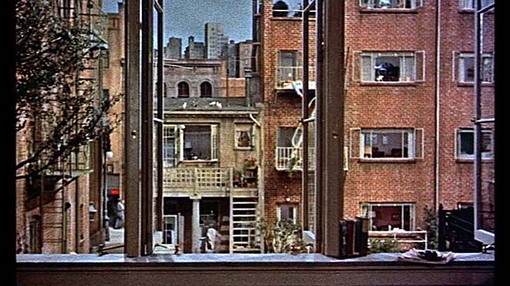

View image

Anyway, so as I told Rob in e-mail, I wanted to respond here with some screen grabs of one of my favorite long takes, and then you over to his place to contribute your own favorites and participate in the discussions. (The problem being, I don’t know how to post screen shots in Comments fields — or if it’s even possible — and this is one you just gotta see, although too few have.)

View image

View image

The movie is Jerzy Skolimowski’s “Moonlighting” (1982), a dark (and dank) comedy about a group of Polish construction workers, led by Nowak (Jeremy Irons), who travel London to do a little off-the-books remodeling at their boss’s flat. Political unrest in Poland makes Nowak’s job as foreman all the more tricky; he withholds information from them, and tries to pretend everything is normal, while carrying an ever-increasing load of fear, guilt and moral responsibility. Ten years later, the Soviet system had collapsed, and you get an eerie sense of why from this movie.

View image

View image

View image

The shot (from a stationary camera; no dollying) begins with Nowak riding his bike toward us, then turning around and riding away. No reason is given for the reversal (the pivotal moment is a pause, almost in close-up), but we know certain decisions are weighing heavily on Nowak’s mind. He heads down the road, and we see a man walking a black dog on the sidewalk. The man and dog begin to cross the street and, just as Nowak is about to disappear around a corner in the distance… a cat jumps into the frame, arching its back at the dog. Man and (reluctant) dog cross to the right; the cat freezes, then continues, bristling, in the opposite direction, left. The cat pauses on the sidewalk, looking at a retaining wall. Just then, Nowak reappears at the end of the street, riding back toward the camera again. The cat jumps. End of shot.

This shot captures the restless, tortuous tensions at work in Nowak’s mind — and in one moment expresses why I love Polish cinema so very deeply. It’s all in the details, the composition, the timing. The absurdity. Moments like this have taught me how to apprehend the world; or, at least, reinforced my existing view — watching Polanski or Kieslowski or Zanussi or Skolimowski has been like coming home, or finding my long-lost twin.

All the time I catch glimpses of weird little things as I’m walking down the street, or through my windshield or in my rear-view mirror when I’m driving, that make me smile or laugh or do a double-take or give me a little chill. And I think: I’ve got to put that in a movie. (Of course, I promptly forget most of these things, but they enhance my enjoyment of life immensely.)

So, either you find this shot funny or you don’t. I gasped with delight the first time I saw it and chuckled for the next few minutes. Maybe you find it simply odd (which it is!) or a little eerie (ditto) or just mundane (instead of inspired). But to me, it’s the essence of movies. Movies!

View image F&A: A theatrical scene.

David Bordwell weighs in on the Great Debate of August with a substantial post called “Bergman, Antonioni, and the stubborn stylists,” in response to Jonathan Rosenbaum — who gives his verdict on a recent viewing of “Fanny and Alexander.”

First, Bordwell offers his perspective:

Timing aside, there wasn’t much in the piece that hasn’t been said by certain cadres of cinephiles for decades. Back in the 1960s, people called Bergman “theatrical,” “uncinematic,” pretentious, and intellectually shallow. He was even accused of hypocrisy. His spiritual, philosophical films always seemed to depend on a surprising number of couplings, killings, rapes, and gorgeous ladies, often naked. Rosenbaum contrasts Bergman with Bresson and Dreyer, more austere religious filmmakers as well as great formal innovators, and this gambit too is familiar from late-night film-society disputes. Jonathan’s case is news in the good, grey Times, but it’s an old story among his (my) generation.

I think that this generational antipathy has many sources. While Bergman had considerable academic cachet, this may have hurt him with smart-alecks like us. Cinephile priests and professors told us that Bergman was a great mind, but we suspected them of snobbery, for they often disdained even foreign filmmakers who dabbled in popular genres. Kurosawa was admired for “Rashomon” and “I Live in Fear” rather than for “Seven Samurai” and “Yojimbo.” And many of Bergman’s intellectual fans despised the classic tradition of American studio film. Hitchcock had not yet convinced literature profs of his excellence, and Ford was a gnarled geezer who made Westerns. Bergman and his acolytes seemed just too square. Our money was on Godard, especially after Susan Sontag’s magisterial essay on him. […]

Speaking just for myself, I didn’t have a deep love for Bergman, and I still don’t. I was drawn to his early idylls (“Monika,” “Summer Interlude”) and impressed but chilled by the official classics (“Smiles of a Summer Night,” “The Seventh Seal,” “The Virgin Spring”). “Persona,” I admit, was a punch in the face. Seeing it in its New York opening, I felt that all of modern cinema was condensed into a mere eighty minutes. But no Bergman film afterward measured up to that for me, and after “The Serpent’s Egg” I just lost interest, catching up with “Cries and Whispers,” “Scenes from a Marriage,” “Fanny and Alexander,” and a very few others over the later decades.

Werner Herzog is a regular. One time I met a man in a cowboy hat on Main Street and he was Jimmy Stewart. I saw Andre Tarkovsky and Richard Widmark exchange shots on the Sheridan Opera House stage (though not on the same night). Krzysztof Zanussi translated forTarkovsky and showed his miraculous “Imperativ.” Kyle MacLachlan and Laura Dern strolled around town, hand-in hand, wearing matching seafoam green outfits and white shoes the year of “Blue Velvet.” I was greeted heartily by Crispin Glover, who momentarily mistook me for director Tim Hunter (“River’s Edge,” “Tex”). I bowed down and kissed Hannah Schygulla’s hand….

Continued below, after jump…

View image David Mamet. What is “liberal,” what is conservative? What is “brain-dead” and what is “knee-jerk”?

The writer of ” Glengarry Glen Ross” and “Wag the Dog,” the writer-director of “House of Games,” “Homicide” and “Oleanna,” reveals in the Village Voice that he doesn’t think people are “basically good at heart” — a belief he ascribes to liberalism. See “Why I Am No Longer a ‘Brain-Dead Liberal’.” As Austin Powers said of Liberace’s homosexuality: Wow, I didn’t see that one coming.

OK, Mamet wrote the piece to be provocative, and I suppose it is, if only because… well, I would wager that far more people fit Mamet’s definition of “brain-dead” than might fit his definitions of “liberal,” “conservative,” “moderate,” “independent,” “libertarian,” etc., put together. His work had not previously led me to think of him as a “bleeding heart” or “brain-dead,” but there you go: Trust the art, not the artist. (Who knew? “Oleanna” was liberal!) Mamet writes:

… I wondered, how could I have spent decades thinking that I thought everything was always wrong at the same time that I thought I thought that people were basically good at heart? Which was it? I began to question what I actually thought and found that I do not think that people are basically good at heart; indeed, that view of human nature has both prompted and informed my writing for the last 40 years. I think that people, in circumstances of stress, can behave like swine, and that this, indeed, is not only a fit subject, but the only subject, of drama.