Robert Wise Movie Reviews

Blog Posts That Mention Robert Wise

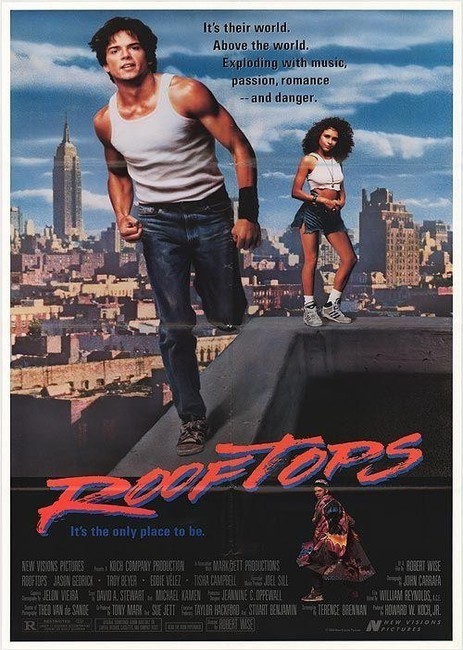

Coming to a bad end

Jim Emerson

The 100 Most Acclaimed Movies of the 20th Century

Jim Emerson

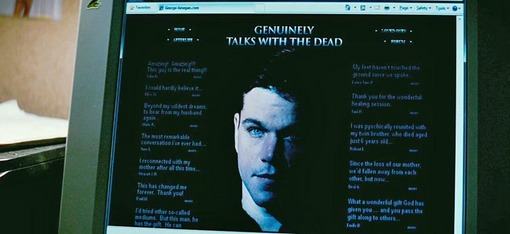

Eastwood, now and Hereafter

Jim Emerson

Experience the Star Trek Movies in 70mm at Out of this World L.A. Event

Craig D. Lindsey

Home Entertainment Guide: January 2024

Brian Tallerico

Noir City Returns to the Music Box in Chicago

Laura Emerick

Academy Museum of Motion Pictures Exhibition, Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898 -1971, Kicks Off with Screening Series

The Editors

Home Entertainment Guide: December 2021, The Criterion Collection

Brian Tallerico

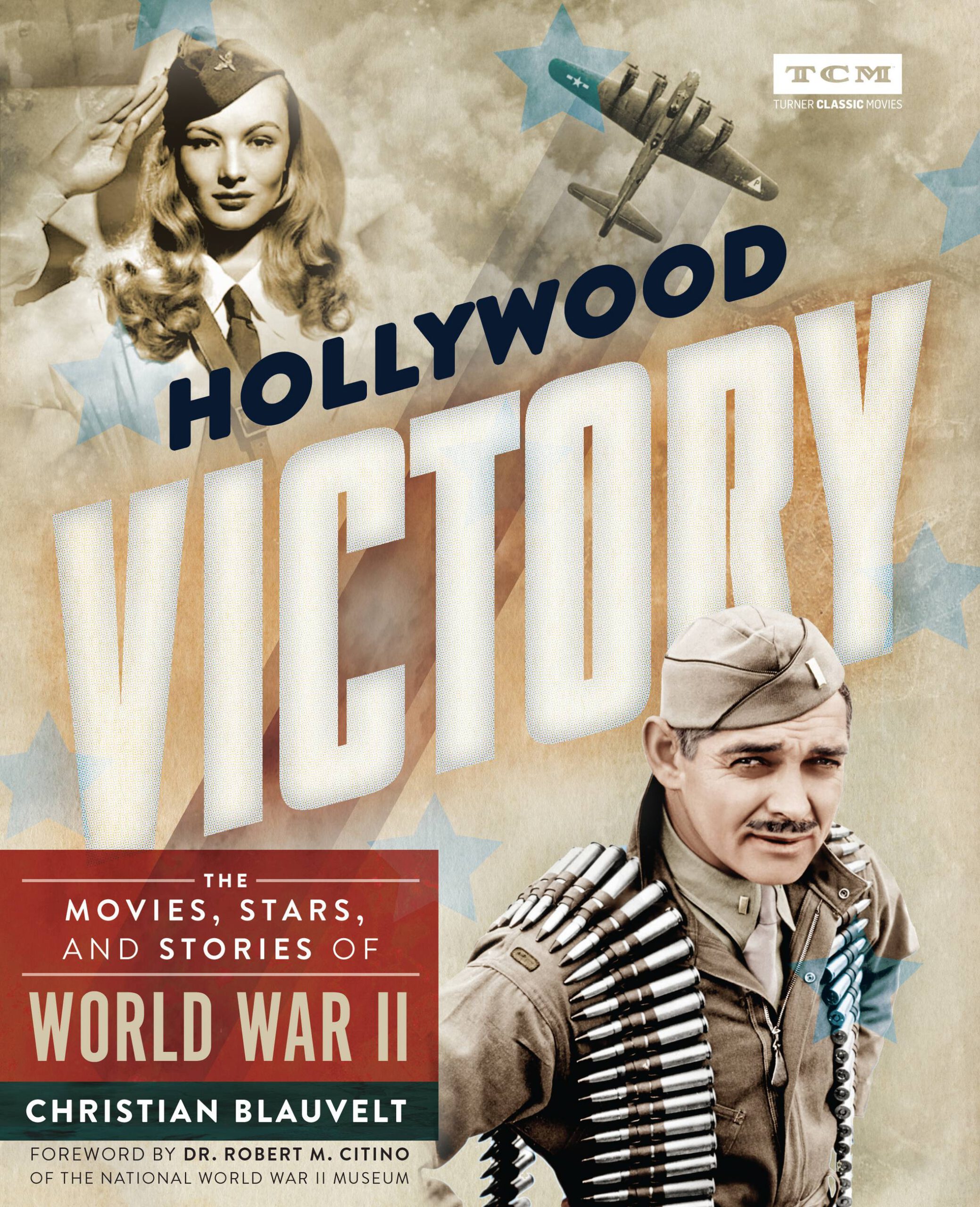

Book Excerpt: Hollywood Victory: The Movies, Stars, and Stories of World War II by Christian Blauvelt

The Editors

Death is Good: The Horror Films of Val Lewton

Bill Ryan

A Way of Giving Back: Julie Andrews and Emma Walton Hamilton on Home Work: A Memoir of My Hollywood Years, Julie’s Library and More

Matt Fagerholm

Preview of Noir City Chicago 2019

Laura Emerick

Son of the father: Peter Fonda, 1940-2019

Matt Zoller Seitz

RIP Cinema: On James Dean’s Disappearance and French New Wave Legacy

Q.V. Hough

Great Movies Return to the Big Screen at Music Box’s 70mm Film Festival

Nick Allen

Star Trek: Discovery Returns to Series’ Musical Roots

Charlie Brigden

Home Entertainment Consumer Guide: March 26, 2014

Brian Tallerico

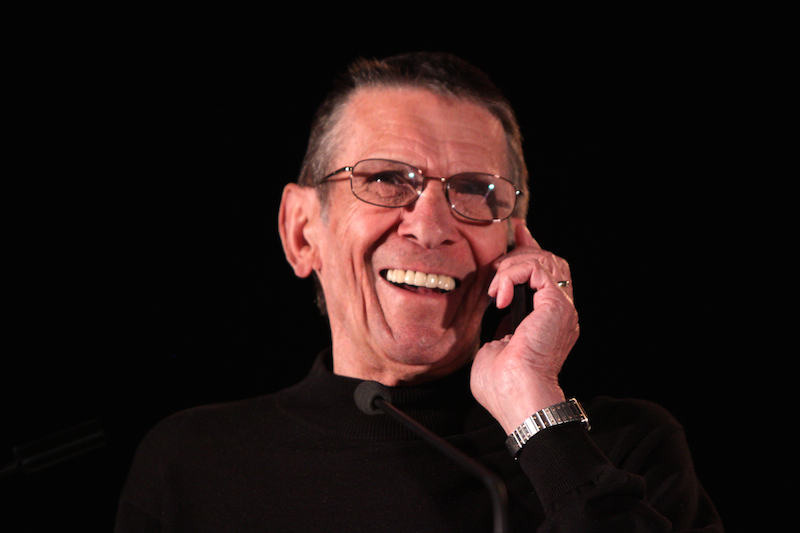

Leonard Nimoy: 1931-2015

Peter Sobczynski

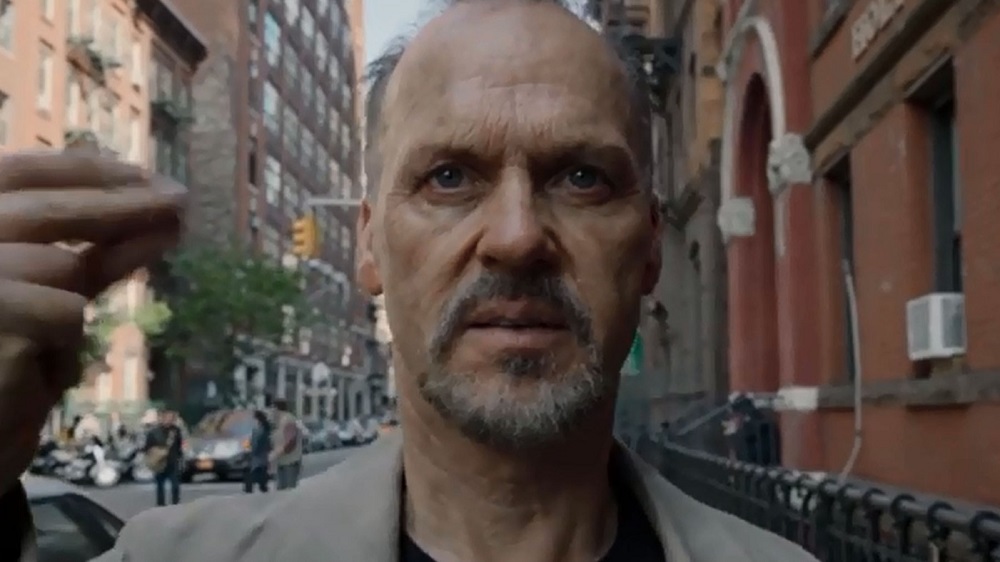

“Birdman,” “Budapest,” Lady Gaga Win Big at Oscars 2015

Matt Fagerholm

101 102 Movies You Must See Before…

Jim Emerson

The Magnificent Ambersons: What’s Past is Prologue

Jim Emerson

Re-imagining the fate of the Holy Grail of cinephilia

Jim Emerson

The Devil and Daniel Webster

Seongyong Cho

On “The Rack” with Paul Newman and Stewart Stern

Jeff Shannon

Interview with Leonard Nimoy

Roger Ebert

Popular Reviews

The best movie reviews, in your inbox