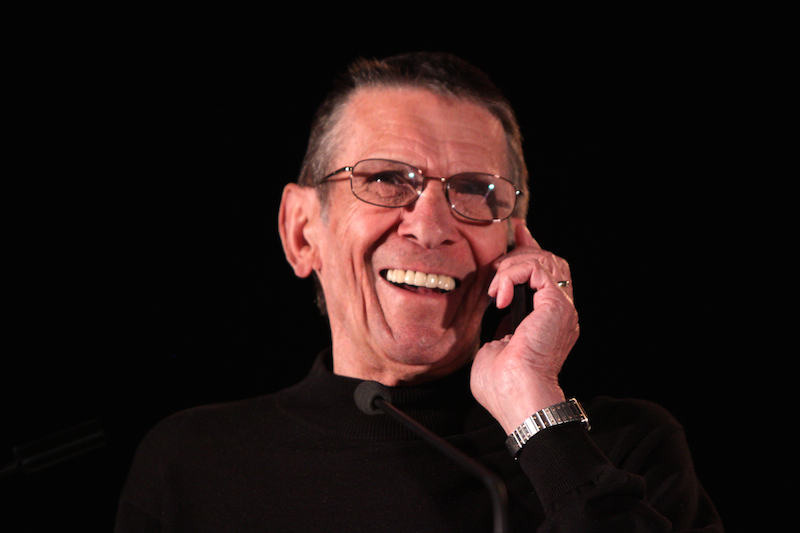

If anyone needed proof as to how beloved Leonard Nimoy was, all they would need to do was look at the Internet to witness the tributes to the man and his long career following the announcement of his passing today at the age of 83 from advanced pulmonary disease, which he was hospitalized for earlier in the week and which he attributed to a smoking habit that he had given up three decades earlier. These weren’t just the normal acknowledgements of the death of a celebrity that one usually sees. These were deeper and more personal, as if someone close to them had died, and showed that to them, he and Spock, the eminently logical Vulcan that he portrayed to perfection on television and on the big screen in the immortal “Star Trek” series, were more than just an actor and a character–they were inspirations who helped to expand their horizons in regards to the possibilities of the world and beyond.

Born on March 26, 1931, Nimoy began acting in local community productions at the age of 8 and had his first major breakthrough at the age of 17 in a production of Clifford Odets’ “Awake and Sing.” He made his screen debut in 1951 with small roles in the comedies “Queen for a Day” and “Rhubarb” and made a memorable appearance as the alien Narab in the 1952 Republic Pictures serial “Zombies of the Stratosphere.” After a hitch in the Army, he spent the next decade appearing in small roles in films such as “Them” (1954), “The Brain Eaters” (1958), and adaptations of two Jean Genet plays, “The Balcony” (1963) and “Deathwatch” (1966). During that time, he made appearances in any number of the popular television series of the time, including “Highway Patrol,” “Sea Hunt,” “Dragnet,” “Bonanza,” “Gunsmoke,” “The Twilight Zone,” “”The Outer Limits” and a 1964 episode of “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” in which he acted opposite another journeyman actor by the name of William Shatner.

In 1966, he would reunite with Shatner and make himself a permanent fixture in the pop culture firmament when he signed on to play the half-human, half-alien Spock in a new science-fiction series from Gene Roddenberry entitled “Star Trek.” The history of that show has been documented in exhaustive detail over the years–how it limped through three years of middling ratings before getting cancelled in 1969, only to become a worldwide sensation through the constant reruns of the 79 episodes, several spin-off series and, after a rocky start, a hugely popular film franchise that continues on to this day. Although Spock, the science officer for the U.S.S. Enterprise, was famous for looking at things from a purely logical and emotion-free perspective, he would turn out to be the heart and soul of the franchise–while Shatner’s Captain Kirk was off performing the usual heroic duties–fighting bad guys, romancing green-skinned babes and speechifying at length (and with more pauses than a Pinter play), Spock allowed viewers to look at the mysteries of space with a more curious and contemplative mindset.

Over the years, Nimoy would have a complex relationship with the character who gave him international fame. On the one hand, he clearly felt a close kinship with the character–it is said that he himself devised two of Spock’s signature moves, the splayed-finger Vulcan salute and the nerve pinch that would knock out enemies instead of blasting them to bits. On the other hand, he would sometimes find it difficult to get people to see him as anything other than that character. He would supply Spock’s voice for an animated “Star Trek” series that ran in the mid-Seventies but when rumors began to surface of a revival of the show proper, either on television or as a movie, there were rumors that he was not interested. In fact, when he wrote his autobiography in 1975, he famously titled it “I Am Not Spock.”

During the immediate post-“Trek” era, he was a regular during the last two seasons of “Mission: Impossible,” served as the host of the oddball documentary series “In Search Of. . . ” and made guest appearances on a number of other television shows. He also appeared on the stage in a number of productions and even recorded five albums, the second of which, 1967’s “Two Sides of Leonard Nimoy,” featured the “Hobbit”-inspired tune “The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins.” In 1978, he would give one of his most notable non-“Trek” performances in Philip Kaufman’s great remake of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers”–as self-help guru Dr. David Kibner, he brilliantly spoofed his persona as a man of logic talking people out of what proved to be very well-founded paranoias about how there is something not quite right with their loved ones. With all due respect to the other versions, this “Body Snatchers” is the best of the bunch in the way that it blends horror and social satire and Nimoy’s performance does a lot to sell both approaches.

Finally, after years of wrangling, “Star Trek” would finally return as a feature film and Nimoy agreed to return as Spock. The end result of all this work and anticipation was “Star Trek-The Motion Picture” (1979), a bloated behemoth of a film that satisfied few (though when director Robert Wise was afforded the chance to recut it years later for home video, that version did play somewhat better) but made enough money to warrant a sequel that would be produced on a much smaller scale. Nimoy was even less eager than before to come back–during this time, he had directed a film version of his one-man play “Vincent” (1981), in which he played Theo van Gogh, and gave an Emmy-nominated performance opposite Ingrid Bergman (in her last role) in the mini-series “A Woman Called Golda”–but agreed to come back with the promise that Spock would be killed off once and for all. Against all odds, this sequel, “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan” (1982) would prove to be a critical and commercial hit and the scene in which Spock gives his life to save the crew of the Enterprise would prove to be a devastating punch in the gut at the end of its hugely entertaining story–the power of Spock’s final moments with his friend Kirk were such that even those who had never seen “Star Trek” before were moved by it.

Of course, the end of “The Wrath of Khan” gave hints that Spock might somehow be resurrected and once the film was released, “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock” went into production. This time around, Nimoy asked for the chance to direct and was hired, the first time a member of the “Trek” cast was hired to work behind the camera as well. When the film was released in 1984, it proved to be another hit and the climactic resurrection of Spock was the Easter Sunday to the previous film’s Good Friday. Not only was Spock reborn, Nimoy now had a new career on his hand as a director–over the next few years, he would make “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home” (1986), the most popular installment of the franchise to date at the time, the very successful “Three Men & A Baby” (1987), the melodrama “The Good Mother” (1988), the grisly Gene Wilder comedy “Funny About Love” (1990) and the barely-released 1994 Patricia Arquette vehicle “Holy Matrimony.”

His association with the “Trek” franchise would continue with “Star Trek V: The Final Frontier” (1989), “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country” (1991), an appearance on television’s “Star Trek: The Next Generation” and cameos in the J.J. Abrams franchise reboots “Star Trek” (2009) and “Star Trek: Into Darkness” (2013)–to solidify his new-found bond with the character, he would title his 1995 autobiography “I Am Spock.” Outside of the “Trek” universe, he would continue to make the occasional guest appearances–oftentimes as a voice actor and usually in genre-related projects. He supplied voices to characters in the animated feature “Transformers: The Movie” (1986) and the live-action cartoon “Transformers: Dark of the Moon” (2011) as well as the Disney “Atlantis: The Lost Empire” (2001). On television, he played himself on episodes of “The Simpsons” and “Futurama,” appeared as a recurring character on the cult sci-fi show “Fringe” and even gave voice to a Spock action figure on “The Big Bang Theory”–all shows that could trace their lineage in some way back to “Star Trek.” Not counting voice work and cameos, Nimoy essentially retired from acting in 2003.

Leonard Nimoy had a fascinating life, both on and off the screen, and it is impossible to gauge just how influential he and his work have been on subsequent generations. I am not just talking about the members of the show’s immediate fan base who have memorized every episode and attend the conventions dressed in their fake ears and arched eyebrows. After all, who knows how many people who watched him as Spock while growing up were inspired by his ideal to themselves go into the scientific and technological fields as a result? Nimoy wasn’t just a star–he was an icon in the best sense of the word and his passing will leave a void with everyone whom he touched with his craft over the years. Of course, to quote a film that presumably does not need to be named, “He’s not really dead, as long as we remember him.”