When I stepped up to buy my ticket for “Hereafter,” the woman in the booth (who has worked there for many years) said, “This movie’s directed by Clint Eastwood.” I know, I said. “He’s not in it,” she said. “I guess it hasn’t been getting very much publicity.”

I don’t know if it has or hasn’t, but it got me to thinking: I’m not sure I could identify a Clint Eastwood movie on sight. Is there an identifiable Eastwood directorial vision or style, apart from a certain willfully “classical” gloss applied to a professional reserve that sometimes borders on indifference? Is he like a William Wyler or a Robert Wise, a journeyman, capable of making some very good movies, whose sensibility is identifiable primarily through the combined talents of his collaborators? Who is Clint Eastwood, the director?

Eastwood hires top-of-the-line folks (after all, he can), has them do their things, and prides himself on shooting the script as written, on time and on (or under) budget. Some very good directors I know don’t consider what he does to be direction so much as project management, because they don’t see anything particularly distinctive in the results, film after film. Still, Eastwood can get movies made that perhaps nobody else could, based on the strength of his commercial reputation and long association with Warner Bros.

Some critics I greatly admire find his work impressive and moving. Many of those who’ve worked with him describe the atmosphere Eastwood fosters on the set as his greatest contribution to the picture: He creates the conditions he needs to get the movie he wants from he people he’s hired — which is, to a lesser or greater extent, what all good directors must do. (See Robert Altman for a striking example.) But, when watching a post-“Unforgiven” Eastwood picture, I frequently detect a peculiar detachment, a feeling that I’m watching something coasting along on auto-pilot without any particular human or artistic vision to guide it.¹ I respond to directors who have been accused of glacial misanthropy — from Antonioni to Kubrick — and that is integral to their worldview. With Eastwood, I simply sense an almost mechanical disengagement from his material. Parts of some of these movies seem to have been made by robots.

“Hereafter” is a network narrative (see “Crash,” “Babel“) unlike anything Eastwood has directed before, and yet it displays the self-consciously sedated rhythms and monochromatic glumness (visual and emotional) familiar from “Mystic River,” “Changeling,” and other latter day Eastwood movies. (It’s a rather affected style, but is that all there is to the Eastwood signature?)

This is a movie preoccupied with death and almost-death, so of course you would expect it to be somber. And because it takes nearly two sullen hours for the three main threads — set in San Francisco, Paris and London — to inevitably intersect, it gives you lots of time to just sit back and wonder how it’s going to maneuver its characters into the same room, and to ponder what all this is supposed to signify.

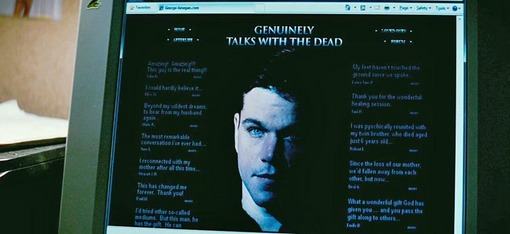

As it turns out, “Hereafter” is not primarily concerned with the afterlife at all, but with a man named George (the always more-than-capable Matt Damon) who believes he has the ability to communicate with the dead when he touches the hands of a grieving relative of the deceased.

Understandably, this talent has proven to be a more of a burden than he can handle, so he has given up his private psychic practice and now works at a C&H Sugar factory warehouse. His brother (Jay Mohr) thinks he has a genuine gift and should put it to use for cash money, but George says it feels more like a curse. Through these portions of the movie, I kept recalling the chilling roller-coaster thrills in David Cronenberg’s icy Stephen King adaptation, “The Dead Zone.” “Hereafter,” though, is bereft of momentum or suspense; it’s pretty much a dramatic flatliner.

George is the movie’s nexus, but it begins by focusing on a French journalist named Marie (Cecile De France), who is swept up in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami (staged with terrifying hyper-stylized realism, if that term makes any sense), leaving her with a concussion and a Near-Death Experience™ by drowning. While unconscious, she remembers seeing a drab white light behind some blurred, shadowy figures. (Let’s just say that the overwhelming share of the effects budget was spent on the tsunami.) This underwhelming vision haunts her. Yet, unlike Marie, after these opening scenes the movie itself never quite seems to emerge from underwater.

Meanwhile, in England, adorable schoolboy twins Jason and Marcus (Frankie and George McLaren) are trying to cope with their junkie/alcoholic mother and the department of social services, when one of the boys is killed in an accident, which is shot exactly the way 90 percent of freshman film school students would have storyboarded it. The death scene is unavoidably tragic — a little kid is killed — but this is one of those passages I felt was assembled by rote: “OK, we’ve got the crane shot. Moving on…”

Eventually, as you might suspect, these storylines converge. (I suppose a spoiler warning would be appropriate here.)

All three of the main characters are emotionally isolated by their experiences with death. Most of the time I had the impression that George, exhausted by the demands of those who seek his services, was telling them what he honestly believed he was hearing from the Other Side — and the movie pointedly contrasts him with theatrical phonies and con artists who are just out to make a buck from the bereaved.

But at other times it seemed to me that he may be doing — in good conscience — just what the fake “psychics” do, which is to tell people what they want to hear, tying up emotional loose ends to make then feel better. There’s a routine, a formula, to his readings: You’ve recently lost someone close to you and that person says he/she wants to apologize to you. The movie leaves room for speculation about the nature of George’s abilities, but he appears to be good at what he does, even if he’s reluctant to do it.

Still, even I could have told him that fluttery Melanie (the ever-mannered Bad Actress Bryce Dallas Howard), whom he meets in an Adult Education Italian cooking class (taught by Steven R. Schirripa, Bobby from “The Sopranos”), was pure phony-baloney from the moment of her kooky/awkward entrance. A blind taste-testing scene in class, which cutely references “9 1/2 Weeks” and goes on far too long, made me doubt that the movie, from Peter Morgan‘s screenplay, had anything but clichés to offer.

Marie remains the most attractive and least interesting character. She did not lose anyone, just herself (briefly), and her desire to understand what happened to her is not developed beyond a scenic trip to Switzerland that allows for a few stunning Alpen exteriors. It is possible that her Near Death Experience™ is what allows for the movie’s romantic Happy Ending, but if that’s the case (hey, George can grasp her hand without wearing a glove ’cause she’s not grieving for a dead relative!), then it amounts to little more than a weak punchline at the end of a 129-minute joke.

What, then, is “Hereafter” ultimately about? An empath who thinks he can communicate with the dead and pass on consoling messages to their relatives (whether he actually receives those messages or not)? People who want to believe that the dead have unsaid things they still need to communicate? I don’t know. I know that when I have lost people dear to me, I sometimes can’t accept that they’re gone until I have a dream in which they appear and help me to let go. Maybe that’s what these people are looking to get from George.

Roger Ebert says that “Hereafter” is about the need some people have to believe in an afterlife, even (according to the subjective descriptions in this movie) if it’s nothing more than a perpetual state of weightless, timeless consciousness. To me, that sounds more or less like others’ descriptions of hell. (My own Near Death Experience™, which consisted of nothingness, does not match up with some of the other common accounts, but that’s neither here nor there as far as the interpretation of this movie is concerned.)

So, let’s look at “Hereafter” as if it were a human life: What meaning does it have? What is the purpose, if any, of its existence (besides an effort to generate revenue)? I’d like to hear what you make of it…

MUST-SEE: Ann Thompson interviews screenwriter Peter Morgan on not working with Clint Eastwood:

– – – –

¹ For what it’s worth, I come neither to exalt nor to bash Eastwood. I think he’s directed one masterpiece, “Unforgiven”; a number of very good movies (“The Outlaw Josey Wales,” “Bronco Billy,” “A Perfect World,” “Flags of Our Fathers,” “Letters from Iwo Jima“); at least two terrible ones (“Mystic River” and “Firefox“); and one that veers unevenly from the sublime to the unforgivable (“Million Dollar Baby“). I haven’t seen his last two pictures, “Gran Torino” and “Invictus” — or a handful of others. As a director, he’s still an enigma to me. I just don’t get a sense of who this guy is from his movies. One of these days, I hope someone will take my hands and, in a flash of blinding insight, the brilliant coherent vision of Director Eastwood will be revealed to me.