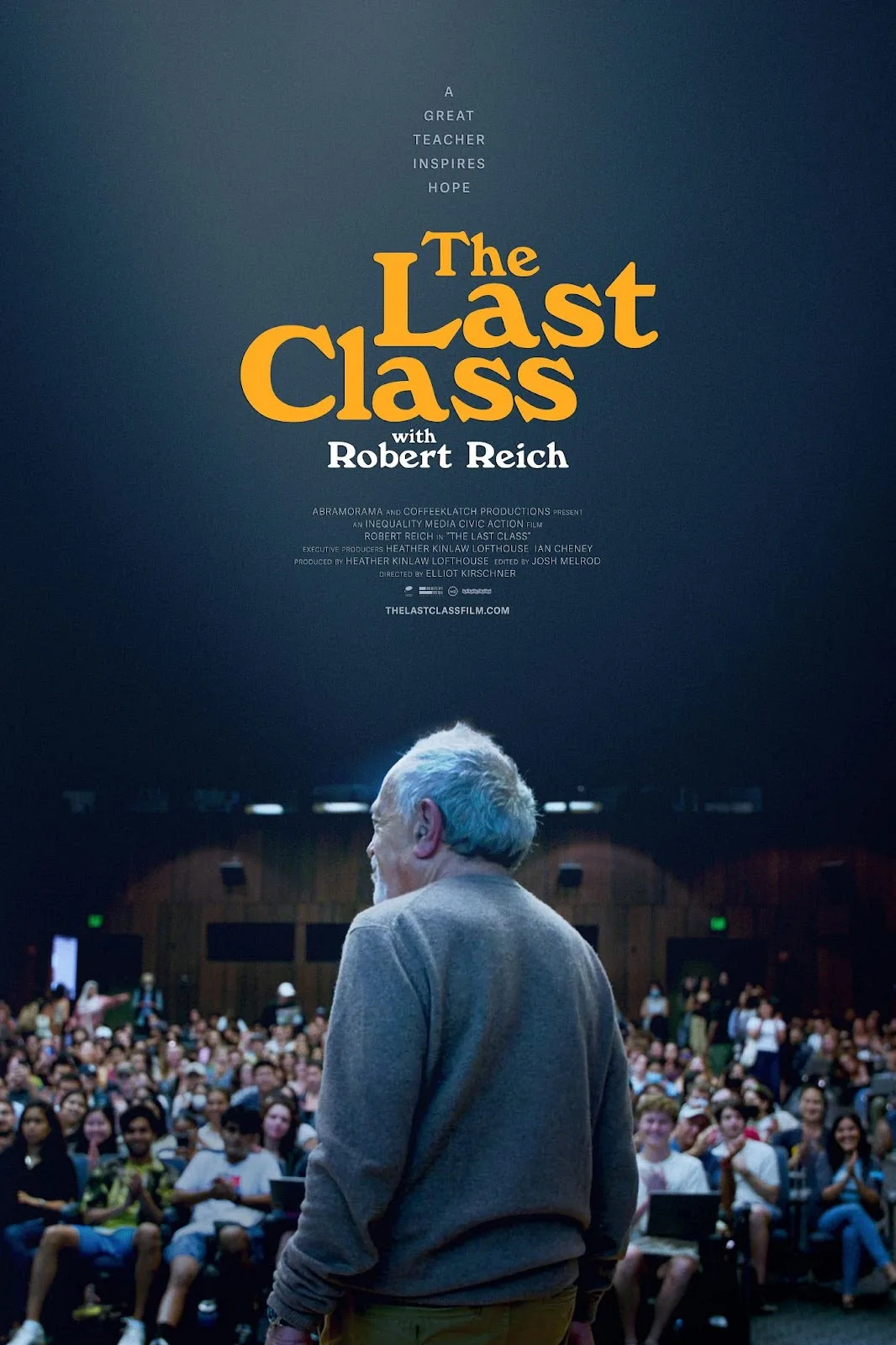

“The Last Class” is an account of the final semester taught by economist, author, former labor secretary, and longtime Berkeley professor Robert Reich, who retired from academia in 2022 after 17 years at the university. The subject of his final course is wealth inequality, which has been in the news more often than at any point since the 1960s. The movie offers a few snippets of Reich talking about it in an auditorium full of students. But the main subject is teaching itself, and by extension, the learning process as it applies to teachers as well as students.

At one point, as Reich is being prepared to go on camera, he wryly assures the crew that he’s done this sort of thing before. That’s an understatement. A montage of research footage interspersed among the movie’s end credits showcases TV appearances dating back to the 1980s. Reich is an eloquent extemporaneous speaker who knows how to keep people’s interest while coming across as authentic. That makes him a perfect subject for a documentary. This is a good one.

If you go into this movie expecting a feature-length account of Reich in the classroom, you’ll be disappointed. Most of the movie consists of Reich ruminating on income inequality, the shaping of public opinion by media and political messages, the democratic process, the importance of publicly funded education, and his own formative experiences. We see enough of Reich in the classroom to understand that he’s very good at teaching, especially when he’s discovering ways to connect with the students. “A good teacher instills both curiosity and critical thinking,” he says.

After segueing out of public service, Reich has become what was once called a public intellectual. The phrase was more esteemed in a time when there were many of them (thirty-plus years ago), the US public school system hadn’t been gutted and muzzled, and the general public was at least somewhat receptive to learning new things and questioning received wisdom, rather than seeking algorithmic confirmation that they were already right about everything.

In appearance, Reich is a classic example of an older male prof who is so happy to be able to live in his head that he’s not interested in looking spiffy, much less TV-ready. His clothes are usually wrinkled, his hair looks like it hasn’t seen a comb in years, and there’s one gray hair spiraling out of his right eyebrow that’s as long as a cat’s whisker. He’s fun to watch and comes across as unpretentious and happy in his own skin.

He cracks a few jokes about his height—he has multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, a form of dwarfism, and titled one of his many economics books I’ll Be Short—but it becomes increasingly clear as the movie unfolds that to students, he casts a big shadow. When Reich asks if it would be OK to invite former teaching assistants to his retirement party, there’s a hint of insecurity, as if he’s worried that attendance will be sparse. The event ends up drawing teaching assistants from multiple states and a four-decade timespan.

You do get the sense that Reich is still somewhat mired in the mindset of an earlier time, when the United States’ two major parties were not yet polarized to the extent where one side wanted to preserve democracy, however imperfectly, and the other sought to dismantle it. At one point, Reich speaks nostalgically of being cordial with Republican legislators, back in the 1990s when he worked for the Clinton administration. Specifically, he calls out his friend Alan K. Simpson, the late Republican senator from Wyoming, whose positions on social issues, especially abortion rights, would identify him as a centrist Democrat today. It’s a different world, to put it mildly.

But all in all, it’s heartening to hear a major figure in American political history talking about the future as if it might actually happen. As Reich approaches the final phase of his teaching career—indeed, his life—he spends increasingly large percentages of his time trying to convince students not to be defeatist about trends in economics and world governance. He doesn’t say exactly what those might be, preferring to let us read between the lines of his economics lessons, which focus on the hoarding of money and resources by the richest people alive and the corresponding deprivation of everyone else.

He seems troubled when he talks about what he sees as the consensus fatalism of his pupils. He says some of them describe themselves as part of “the last generation,” as in ever. He asked them, “Are you so laden with a sense of doom that you think everything will end?” Their responses confirmed that they didn’t think “the world will survive in anything close to [the condition] in which it now exists.” Pushing back against that became his most important mission. “Pessimism is fine,” he says. “Cynicism is not.”