Howard Hughes in his last two decades sealed himself away from the world. At first he haunted a penthouse in Las Vegas, and then he moved to a bungalow behind the Beverly Hills Hotel. He was the world’s richest man, and with his billions bought himself a room he never left.

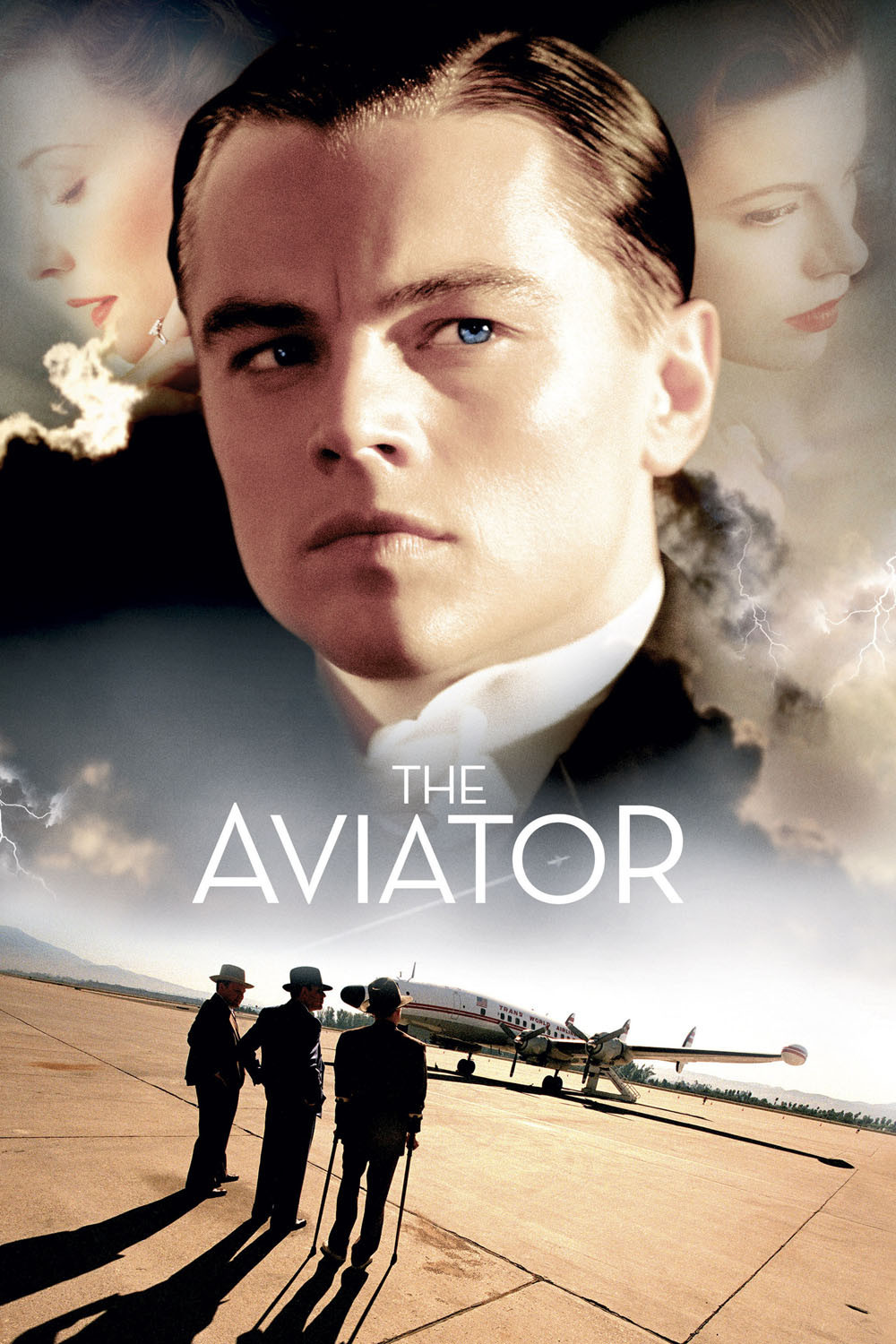

In a sense, his life was a journey to that lonely room. But he took the long way around: As a rich young man from Texas, the heir to his father’s fortune, he made movies, bought airlines, was a playboy who dated Hollywood’s famous beauties. If he had died in one of the airplane crashes he survived, he would have been remembered as a golden boy. Martin Scorsese’s “The Aviator” wisely focuses on the glory years, although we can see the shadows falling, and so can Hughes. Some of the film’s most harrowing moments show him fighting his demons; he knows what is normal and sometimes it seems almost within reach.

“The Aviator” celebrates Scorsese’s zest for finding excitement in a period setting, re-creating the kind of glamor he heard about when he was growing up. It is possible to imagine him wanting to be Howard Hughes. Their lives, in fact, are even a little similar: Heedless ambition and talent when young, great early success, tempestuous romances and a dark period, although with Hughes it got darker and darker, while Scorsese has emerged into the full flower of his gifts.

The movie achieves the difficult feat of following two intersecting story arcs, one in which everything goes right for Hughes and the other in which everything goes wrong. Scorsese chronicled similar life patterns in “GoodFellas,” “Raging Bull,” “The King of Comedy,” “Casino,” actually even “The Last Temptation of Christ.” Leonardo DiCaprio is convincing in his transitions between these emotional weathers; playing madness is a notorious invitation to overact, but he shows Hughes contained, even trapped, within his secrets, able to put on a public act even when his private moments are desperate.

His Howard Hughes arrives in Los Angeles as a good-looking young man with a lot of money, who plunges right in, directing a World War I aviation adventure named “Hell’s Angels,” which was then the most expensive movie ever made. The industry laughed at him, but he finished the movie and it made money, and so did most of his other films. As his attention drifted from movies to the airplanes in his films, he began designing and building aircraft and eventually bought his own airline.

Women were his for the asking, but he didn’t go for the easy kill. Jean Harlow was no pushover, Ava Gardner wouldn’t take gifts of jewelry (“I am not for sale!”), and during his relationship with Katharine Hepburn, they both wore the pants in the family. Hepburn liked his sense of adventure, she was thrilled when he let her pilot his planes, she worried about him, she noted the growing signs of his eccentricity, and then she met Spencer Tracy and that was that. Hughes found Jane Russell and invented a pneumatic bra to make her bosom heave in “The Outlaw,” and by the end he had starlets on retainer in case he ever called them, but he never did.

DiCaprio is nobody’s idea of what Hughes looked like (that would be a young Sam Shepard), but he vibrates with the reckless spirit of the man. John C. Reilly plays the hapless Noah Dietrich, his right-hand man and flunky, routinely ordered to mortgage everything for one of Hughes’ sudden inspirations; Hughes apparently became the world’s richest man by going bankrupt at higher and higher levels.

Scorsese shows a sure sense for the Hollywood of that time, as in a scene where Howard, new in town, approaches the mogul L.B. Mayer at the Coconut Grove and asks to borrow two cameras for a big “Hells’ Angels” scene. He already had 24, but that was not enough. Mayer regards him as a child psychiatrist might have regarded the young Jim Carrey. Scorsese adds subtle continuity: Every time we see Mayer, he seems to be surrounded by the same flunkies.

The women in the film are wonderfully well cast. Cate Blanchett has the task of playing Katharine Hepburn, who was herself so close to caricature that to play her accurately involves some risk. Blanchett succeeds in a performance that is delightful and yet touching; mannered and tomboyish, delighting in saying exactly what she means, she shrewdly sizes up Hughes and is quick to be concerned about his eccentricities. Kate Beckinsale is Ava Gardner, aware of her power and self-protective; Gwen Stefani is Jean Harlow, whose stardom overshadows the unknown Texas rich boy, and Kelli Garner is Faith Domergue, “the next Jane Russell” at a time when Hughes became obsessed with bosoms. Jane Russell doesn’t appear in the movie as a character, but her cleavage does, in a hilarious scene before the Breen office, which ran the Hollywood censorship system. Hughes brings his tame meteorology professor (Ian Holm) to the censorship hearing, introduces him as a systems analyst, and has him prove with calipers and mathematics that Russell displays no more cleavage than a control group of five other actresses.

Special effects can distract from a film or enhance it. Scorsese knows how to use them. There is a sensational sequence when Hughes crash-lands in Beverly Hills, his plane’s wing tip slicing through living room walls seen from the inside. Much is made of the “Spruce Goose,” the largest airplane ever built, which inspires Sen. Owen Brewster (Alan Alda) to charge in congressional hearings that Hughes was a war profiteer. Hughes, already in the spiral to madness, rises to the occasion, defeats Brewster on his own territory and vows that the plane will fly — as indeed it does, in a CGI sequence that is convincing and kind of awesome.

By the end, darkness is gathering around Hughes. He gets stuck on words and keeps repeating them. He walks into a men’s room and then is too phobic about germs to touch the doorknob in order to leave; with all his power and wealth, he has to lurk next to the door until someone else walks in, and he can sneak through without touching anything. His aides, especially the long-suffering Dietrich, try to protect him, but eventually he disappears into seclusion. What a sad man. What brief glory. What an enthralling film, 166 minutes, and it races past. There’s a match here between Scorsese and his subject, perhaps because the director’s own life journey allows him to see Howard Hughes with insight, sympathy — and, up to a point, with admiration. This is one of the year’s best films.