Documentary is a filmmaking approach inherently designed for remembrance. In fact, it’s the approach that most closely aligns with photography and the desire to capture a moment, a person, or a thing before the forces of time overcome and erase its existence. So, you know, usually with these films, you’re going to get a topic of some import. The three films in this Chicago International Film Festival dispatch take the form’s ability to heart in a bid to preserve the memories of a Kosovo village, the legacy of a disgraced Ghanaian president, and an area of Italy previously wiped out by a volcano. These films, to varying degrees of success, stand as a testament to the importance of remembrance, even when the memories hurt.

For the last year or so, cinema has been inundated with films about unmoored individuals and shaken communities grappling with the loss of their homelands. Swiss-Albanian director Dea Gjinovci’s elegiac documentary “The Beauty of the Donkey” is a fine addition to that trend. It concerns the filmmaker’s father, who returns to his small village in Kosovo with his daughter for the first time in nearly 60 years. While there, her father, Asllan, shares memories that Gjinovci decides to stage as abstract theatrical productions, bringing the past back to modernity with potency.

This is also a film that mixes politics with loss. In 1968, a 19-year-old Asllan was a political activist when he was exiled. Upon leaving the country, he lost contact with his family, particularly his mother, whose death has always lived in family lore. Asllan shares the oppression his family suffered under Serbian authorities and the risks taken to combat their rule with stunning clarity; he also investigates his mother’s death with equal fervor. These family stories, of course, impact Gjinovci as well. Because she grew up in Switzerland, she’s never seen her father’s homeland. In the opening sequence, when Asllan emerges from the woods, walking toward the field where his stone home once stood, in the assuredness of her lens, you can feel the haunting reverence Gjinovci has for this moment.

Despite the film’s fanciful title, however, there aren’t many donkeys in this picture. Two scenes featuring donkeys bookend the work, and while you can certainly sense how the animal traces back to a moment of innocence in Asllan’s life and serves as a reminder of his own endurance, the moments don’t cohere enough to be the film’s throughline. Instead, the film is strongest when it doesn’t give way to twee metaphorical scenes, but focuses on the cathartic reclamation of one’s history.

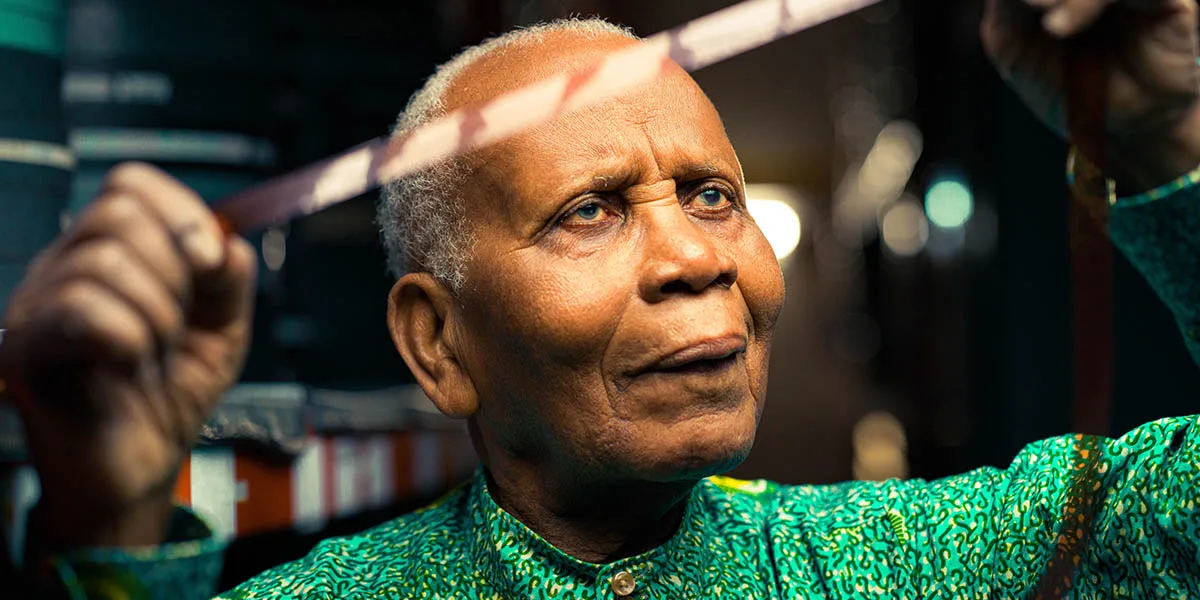

I really wish director Ben Proudfoot’s messy historical documentary “The Eyes of Ghana,” a partial product of executive producers Michelle and Barack Obama’s Higher Ground Productions, were better. It’s one of those films whose desire to tell a little-known story grants it some slack, but whose unsteady execution quickly evaporates much of the goodwill you came into it with. The film concerns legendary Ghanaian cinematographer and director Chris Hesse’s desire to reclaim over a thousand cans of footage from London that he shot of the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, before the leader’s downfall from a military coup in 1966. While that story alone would make for an incredible documentary, Proudfoot overpacks “The Eyes of Ghana” with far too many other threads, leaving it all to fall apart.

Proudfoot is a two-time winner of the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Film (“The Last Repair,” “The Queen of Basketball”), a background you can unfortunately feel when “The Eyes of Ghana” begins with the three cold opens. The first opener introduces Hesse; the second introduces his protege, director Anita Afonu; the third introduces the steadfast projectionist at Ghana’s Rex Cinema, Addo, who often dreams of hosting film at the disused movie house again. With that set-up, you can pretty much guess where this film will end up. Nevertheless, Proudfoot doesn’t neatly interweave these threads. He continues shifting subjects, giving us the early history of Ghanaian moviemaking, Nkrumah’s troubled story, and how America disrupted the Pan-Africa movement via destabilizing newly independent governments. Rather than making a coherent feature out of these varied topics, unfortunately, Proudfoot has produced several shorts whose combined work lacks the focus of a feature.

His film is further hobbled when he begins including the digitized and restored pieces that Hesse shot (in a sense, “The Eyes of Ghana” is a well-meaning advertisement for further funds to restore the rest of Hesse’s stored footage). Not because the images aren’t exceptional, but because Hesse’s films are so much better than the movie we’re watching, which relies on a garish Disney-esque score by Kris Bowers and an on-the-nose desire to capture Hesse at such an angle that we’re always staring deeply into his eyes. Though Proudfoot clearly has an appreciation for the material—“Rwanda and Juliet,” his only other feature, considered the post-genocide lives of that African country—this film is too slick and too broad for such a sensitive story.

The history of Vesuvius, whose eruption led to the decimation of Pompeii, has served as a shot that continues to be heard round the world. So when Gianfranco Rosi’s gorgeous, black and white shot documentary “Below the Clouds” fixes its lens on the mountain, you immediately expect his film to hyper focus on that looming threat. But Rosi, whose previous films include overtly political works like “Fire at Sea” and “Notturno,” rarely takes notice of the life inside the volcano. He instead weaves through the ordinary life bustling around Naples and the recording of lives long past gone by the archeologists excavating local historical sites.

“Below the Clouds” isn’t a talky documentary, per se. It’s totally observational. Even so, Rosi’s meditative lens notices the chatter emanating from its many locations. There’s the emergency call center, where people call for assistance after every tremor. While you’d think these would be intense communications, their inherent franticness is cut down by the humor and sweetness of the officials taking these calls. There is greater chatter among Syrian boatmen seeking entry into the port to deliver their Ukrainian grain. And even more talk ensues whenever we jump into the work of archaeologists, who are navigating, at times, vast tunnels and excavated caverns that hold the frozen, calcified victims of Pompeii.

When combined, these scenes form a documentary fascinated by the fragility and suspension of life. The rhythmic editing, for instance, creates a circular pattern, returning to and remixing images whose continual convergence imbues them with great meaning. Rosi also ventures into a movie house, where he plays films like “Last Days of Pompeii” (1913) and “Voyage to Italy” (1954), which speak to the long-held cultural fascination with an event that continues to fascinate outsiders and remains ever prevalent in the minds of those living near the famed volcano. In a sense, by locking his contemporary documentary in this rich black and white photography, Rosi has also put his film along with those. Thereby, preserving the artifacts of memory that make this place home.