Francis Coppola Movie Reviews

Blog Posts That Mention Francis Coppola

Interview with Robert Duvall & Francis Coppola

Roger Ebert

Coppola looks forward to his own films

Roger Ebert

Thumbnails 10/08/2013

Matt Zoller Seitz

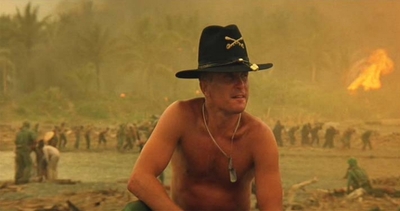

Robert Duvall: “Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that”

Roger Ebert

Chicago Critics Film Festival Announces Full Schedule, Special Guests

The Editors

Let The Dead Sleep: On “Alien Romulus” and Digital Resurrection

Matt Zoller Seitz

There Will be No Questions: The Parallax View, the Ultimate Conspiracy Thriller, Turns 50

Matt Zoller Seitz

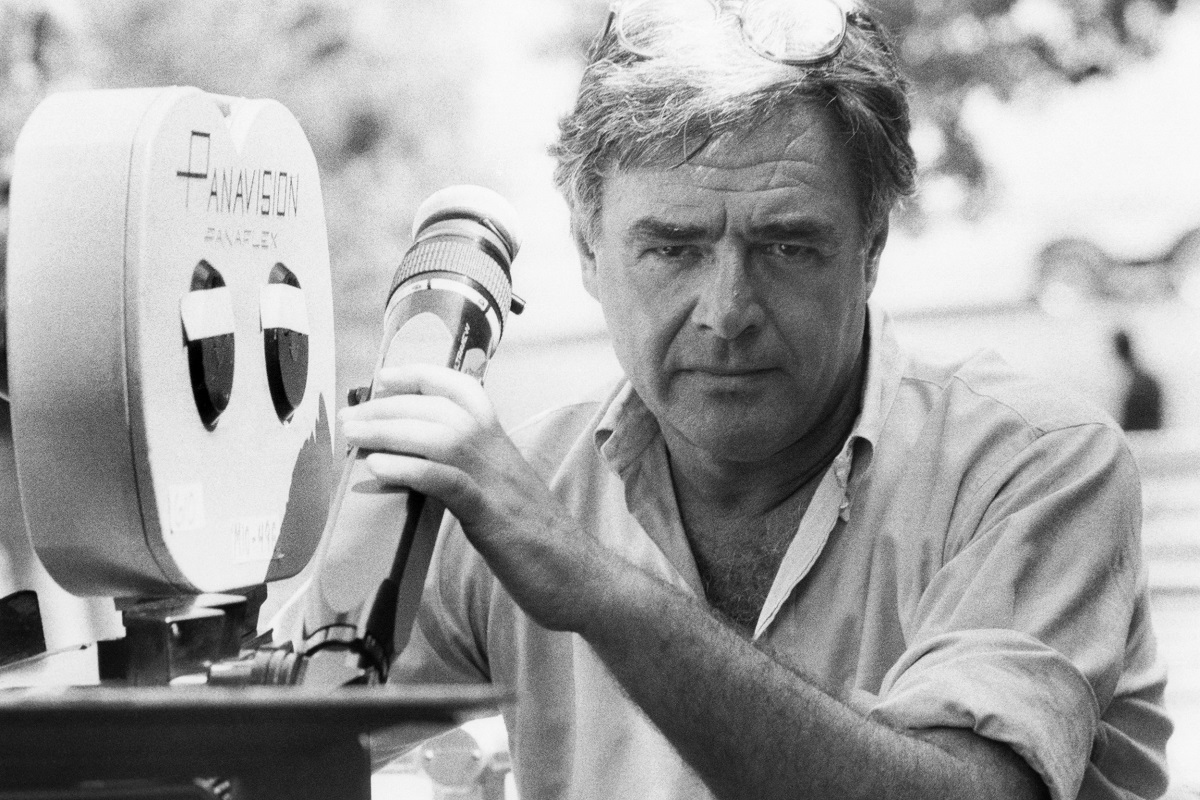

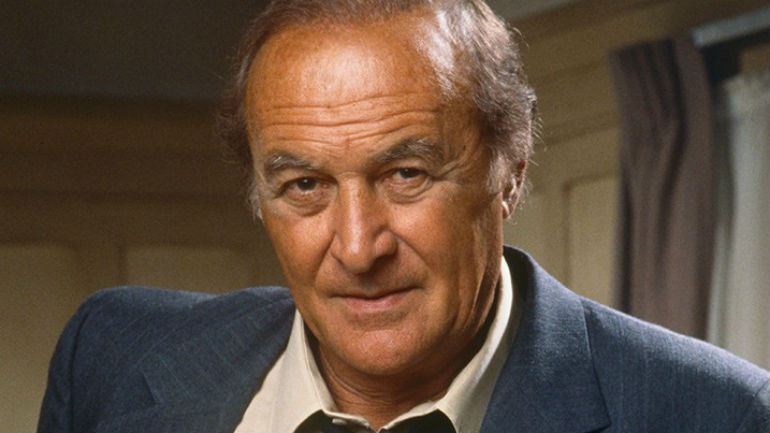

Roger Corman’s Greatest Legacy Was Giving So Many People Their Big Break

Matt Zoller Seitz

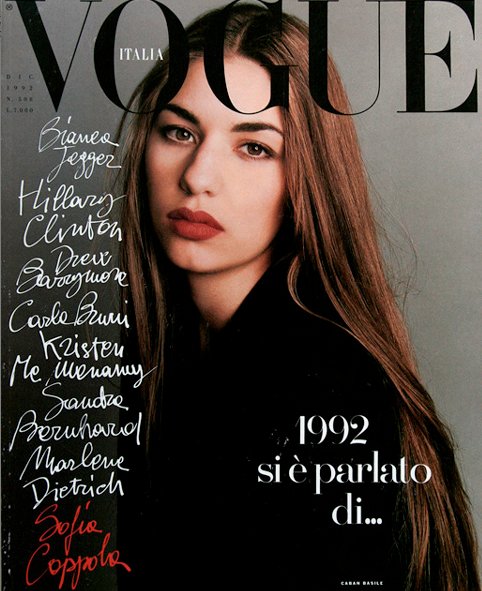

Tom Luddy (1943-2023)

The Editors

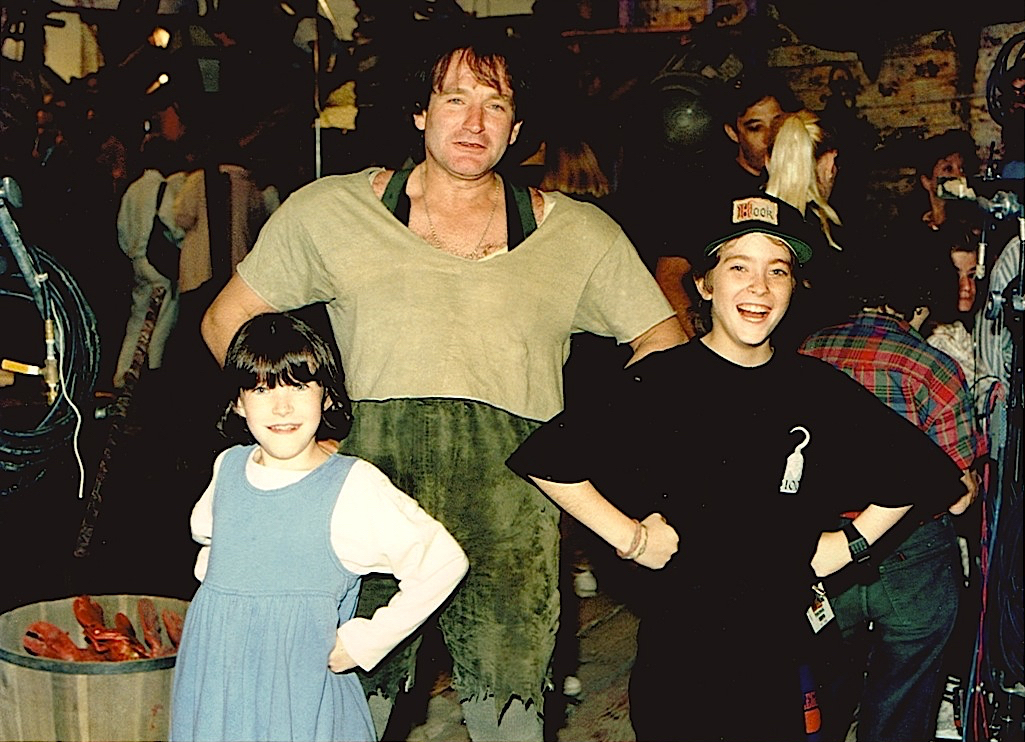

Defying Gravity: Dante Basco, Caroline Goodall, James V. Hart, Charlie Korsmo and More on the Thirtieth Anniversary of Hook

Matt Fagerholm

Richard Donner: 1930-2021

Peter Sobczynski

Monte Hellman: 1932-2021

Scout Tafoya

NYFF 2020: The Human Voice, The Woman Who Ran, French Exit

Odie Henderson

Hal Hartley on His Film Career, Modernist Influences, and Re-Watching His Work

Vikram Murthi

Home Entertainment Guide: September 5, 2019

Brian Tallerico

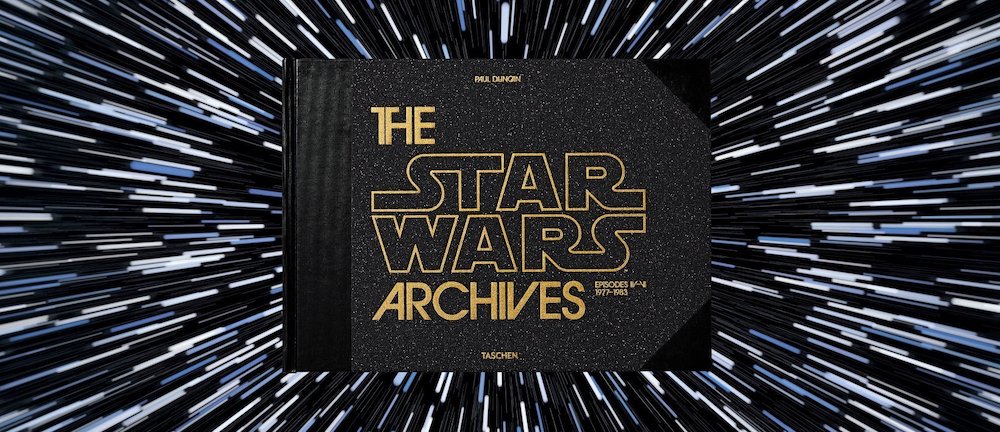

Book Review: The Star Wars Archives 1977-1983

Peter Cowie

CIFF 2018: Friedkin Uncut, The Great Buster

Peter Sobczynski

Amandla Stenberg and George Tillman, Jr. on Bringing Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give to the Big Screen

Nell Minow

The Greatest Show on Earth: Recap of the 2017 Telluride Film Festival

Meredith Brody

Charles Taylor on His New Book, “Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You”

Sheila O'Malley

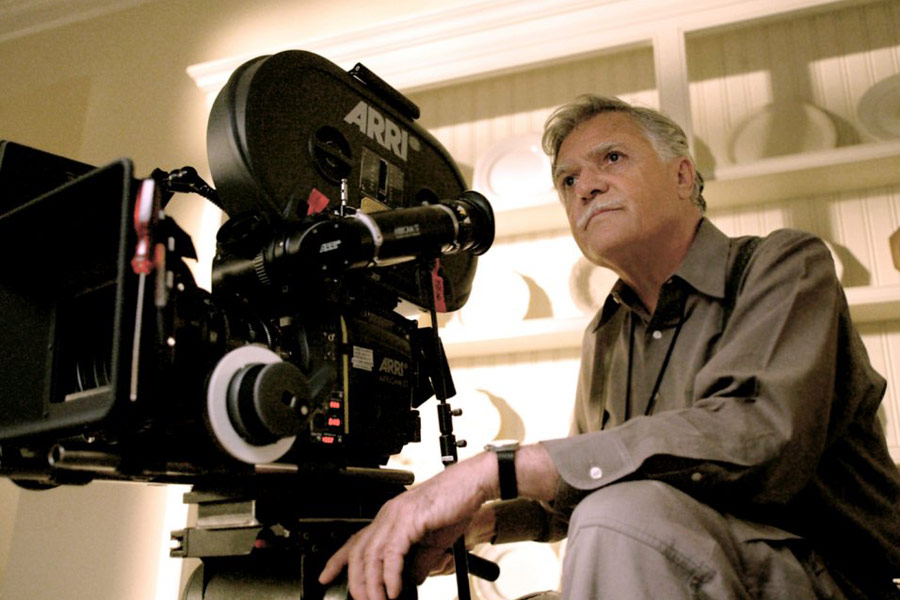

Michael Ballhaus: 1935-2017

Peter Sobczynski

Molly Haskell on feminism, censorship, screwball comedy, and life after Andrew Sarris

Matt Zoller Seitz

Thumbnails 6/17/16

Matt Fagerholm

Robert Loggia: 1930-2015

Peter Sobczynski

At Last! “The End of the World” is Here!

Peter Sobczynski

Who’s Who In Reviews: Peter Sobczynski

Chaz Ebert

Beyond Narrative: The Future of the Feature Film

Roger Ebert

Working From the Heart: The Career of Nastassja Kinski

Peter Sobczynski

The art of darkness: Robert Yeoman on Gordon Willis

Matt Zoller Seitz

Meet the Writers: Peter Sobczynski

The Editors

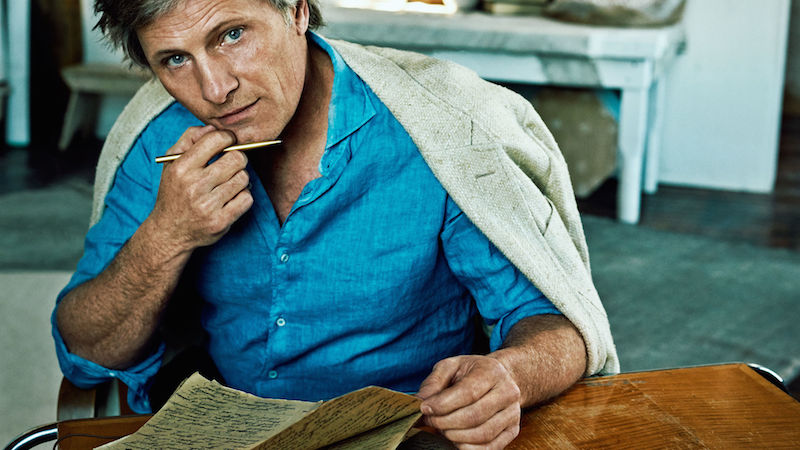

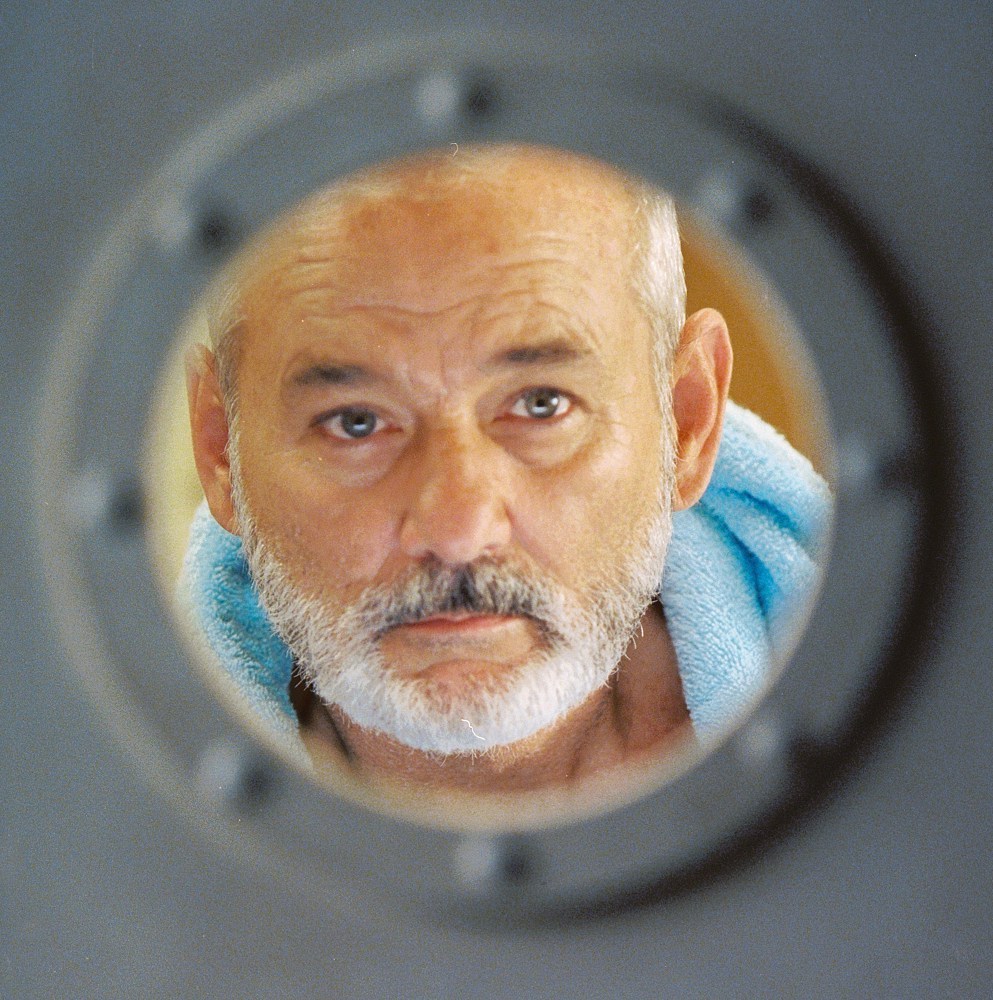

The Wes Anderson Collection, Chapter 4: “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou”

Matt Zoller Seitz

Thumbnails 9/4/2013

The Editors

Book Excerpt: Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses

The Editors

Thumbnails 6/14/2013

The Editors

Thumbnails 6/12/2013

The Editors

My Ten Greatest Movies

Omer M. Mozaffar

Steven Spielberg’s legacy

Roger Ebert

The Best 10 Movies of 1989

Roger Ebert

The Best 10 Movies of 1988

Roger Ebert

The Great Box-Office Scam

Roger Ebert

Apocalypse Now: An audio-visual aid

Jim Emerson

Shooting the rapids with Werner Herzog (Part 1)

Jim Emerson

How much spoilage does a spoiler really spoil?

Jim Emerson

George Lucas: Give it up

Jim Emerson

The direct-to-video king

Roger Ebert

Lee’s ‘Summer of Sam’ a sizzling look at ’70s N.Y.

Roger Ebert

Mission Probable: Oscar for Landau

Roger Ebert

Oscar Noms: Kramer & All That Jazz

Roger Ebert

Andrew Sarris, 1928-2012: In Memoriam

Roger Ebert

Quirky filmmaker soldiers on

Roger Ebert

Brando was a rebel in the movies, a character in life

Roger Ebert

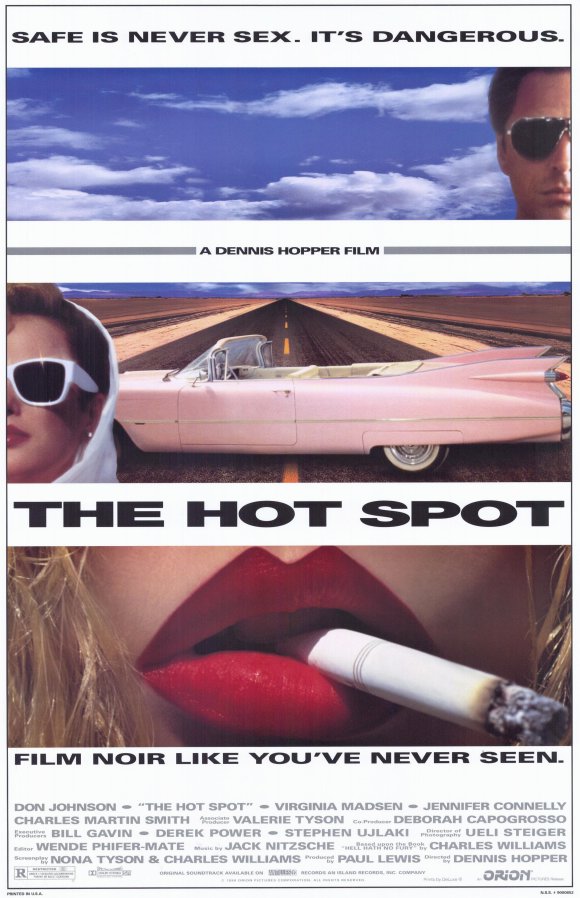

Hopper elicits cool era with his ‘Hot Spot’

Roger Ebert

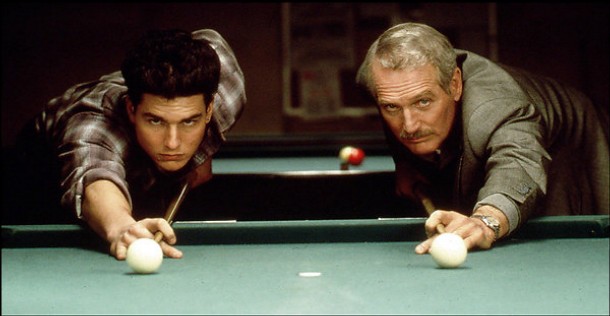

Tom Cruise: Color him bankable

Roger Ebert

Norman Mailer: Tough guy directs

Roger Ebert

Interview with Bette Midler

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (12/20/2007)

Roger Ebert

If at first you don’t succeed …

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (12/13/1998)

Roger Ebert

Popular Reviews

The best movie reviews, in your inbox