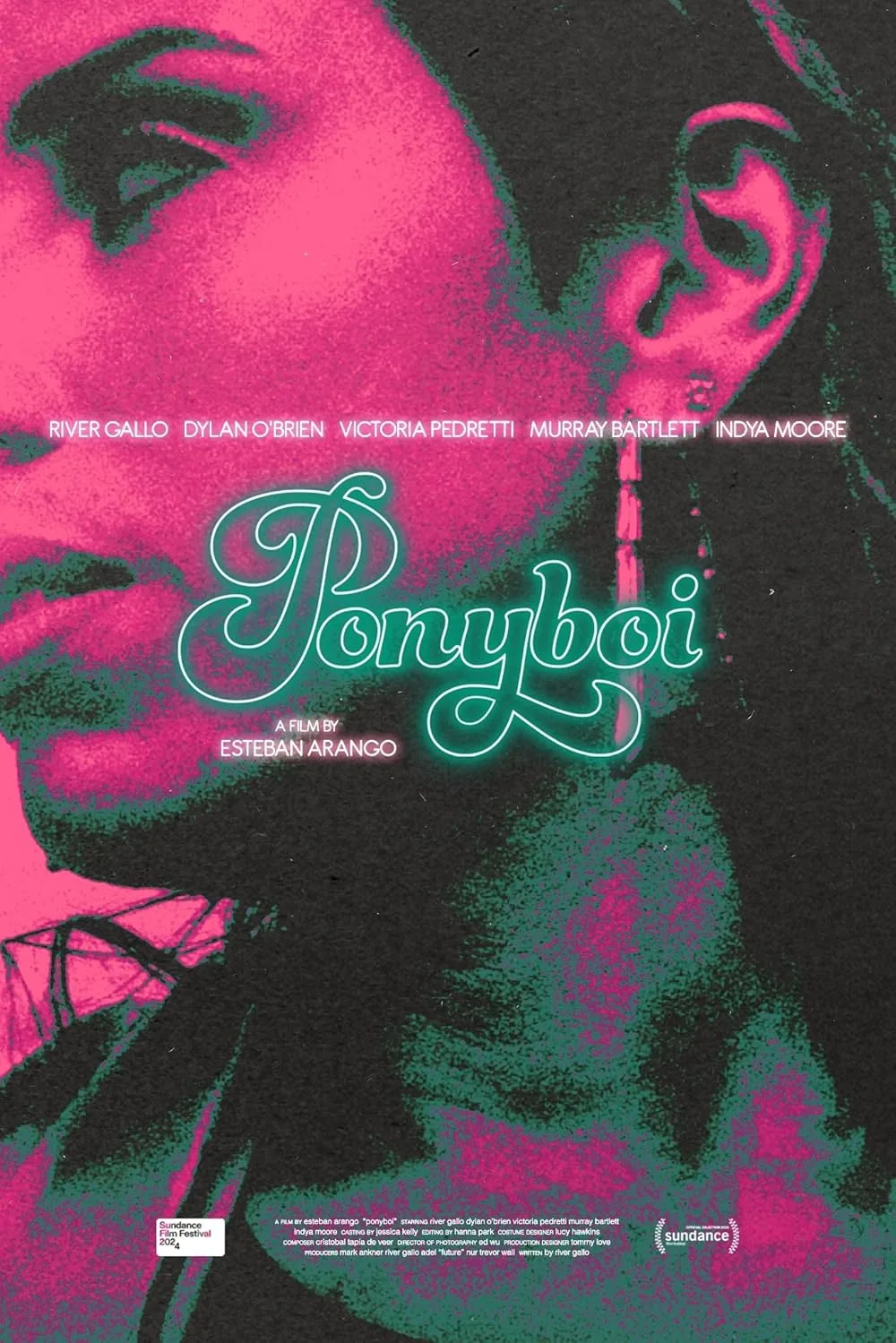

On the one hand, “Ponyboi,” directed by Esteban Arango and written by River Gallo (who stars as the title character), is a crime movie where very little happens that you can’t see coming a mile away. On the other hand, there’s this authentic strain of melancholy and romance in its mood, color palette, and needle drops, which launches “Ponyboi” above genre and into something else entirely. It’s a very uneven mix. The quiet character-based scenes are often mesmerizing, as are the dreamy sequences where time seems to stand still. When the plot makes its demands, the spell is broken.

Ponyboi is an intersex sex worker living in New Jersey, cruising for tricks at truck stops and docks, while also “entertaining” in the back room of a laundromat run by a drug-dealing pimp named Vinny (Dylan O’Brien), whose pregnant girlfriend Angel (Victoria Pedretti) is Ponyboi’s good pal. Angel has no idea Vinny is also sleeping with Ponyboi. Vinny has a small stable of girls working for him, and it’s all quite casual and friendly, until a series of events pile up, and when a couple of scary Mob guys, one of whom is wearing black and white spats like a Damon Runyon bookie, show up in the laundromat, Ponyboi is forced to go on the run.

“Ponyboi” is worth seeing for many reasons, the main one being Gallo. When the feature premiered at Sundance, Gallo, an openly intersex actor, said they were interested in expressing “the different ways in which I felt like an outsider in my life, with intersecting identities—being intersex, being Latinx, being from New Jersey.” Coming from such a personal place and such a unique set of circumstances, Gallo’s focus somehow translates as universal. This is an interesting phenomenon worth keeping in mind. Thomas Hardy’s novels all took place on practically the same patch of land. To the charge that his work was “provincial,” Hardy replied, “A certain provincialism is invaluable. It is the essence of individuality.” This is what the filmmaker has tapped into.

While there aren’t too many exterior scenes, the film is steeped in New Jersey air. It couldn’t be anywhere else. As someone who has lived in New Jersey for decades, in Bayonne, Union City, and Weehawken, the feeling is unmistakably familiar. In a day and age when so many things are filmed in cities meant to be stand-ins for other cities, when so many films have almost zero sense of place, “Ponyboi” wears its regionalism proudly. It’s not “background”. It’s not about good location scouting. It’s the feeling of it. New Jersey is its own thing, and Gallo knows it intimately. DP Ed Wu does not film “Ponyboi” as though it’s a gritty realist film. He goes full-on noir-romantic, with deep shadows melting into pools of color, blurry neon pouring through the windows, colored light falling on the actors’ faces. The film has a very intriguing look.

The deepest parts of the film are the scenes between Ponyboi and Bruce (Murray Bartlett), a guy in a cowboy hat driving a Mustang, who enters the laundromat one night. The two strike up a conversation. There’s an instant chemistry, but it’s an ambiguous one, not just sexual. It’s like two souls are meeting. The dialogue doesn’t sound like words on a page. It sounds like how people talk:

“I’m Bruce.”

“Oh, like Springsteen.”

“Are you a fan?”

“Every Jersey girl is.”

“What’s your favorite song?”

“That’s tough. Probably ‘I’m on Fire’. You know that one?”

It’s hypnotic. He encourages Ponyboi to sing a little bit, and the two sing “I’m on Fire.” They are standing in a grimy, fluorescent-lit laundromat, with a sleazy sex room in the back, and they have created a safe space of play and connection. Bruce exits the film, but he will return. There is a scene between them in a classic New Jersey diner, where they seem to be the only patrons, where the lights blaze through the windows, almost like the diner is a spaceship floating above the earth. The music is romantic, 1950s doo-wop.

Gallo co-directed “Ponyboi” first as a short in 2019. The short didn’t have all the bells and whistles of gangsters and drug deals. It’s a much simpler, close-to-home story. Ponyboi has vague dreams of getting out, of seeing the world, finding love. Bruce is the ultimate fantasy: a casually masculine person, in a cowboy hat no less, who accepts Ponyboi for who they are. The short kept its focus on Ponyboi, aside from any machinations of the plot. They are extremely watchable, vulnerable, and sweet, but also tough and resourceful. Whatever is happening always seems authentic.

Part of this has to do with a sense of place, as mentioned earlier. I’ve often bemoaned how so many actors seem like they don’t come from anywhere specific. Regionalisms and accents are flattened, erased. It’s so refreshing to watch actors like Natasha Lyonne, Annabella Sciorra, Barbra Streisand, Lady Gaga … who feel like they come from someplace very real. They haven’t erased their origins. Their origins are in their accents, mannerisms, and gestures. Gallo is in their company.

“Ponyboi” was a frustrating watch. The Ponyboi-Bruce scenes had so much more vitality than the plot surrounding it. There seemed to have been an obligation felt to add more stuff onto the story, bulking up the crime element, as though nobody trusted that following around an interesting character for a couple of days could hold an audience’s interest. Audiences are interested. Ponyboi is not someone we’ve seen on film before. There’s way more here to explore.