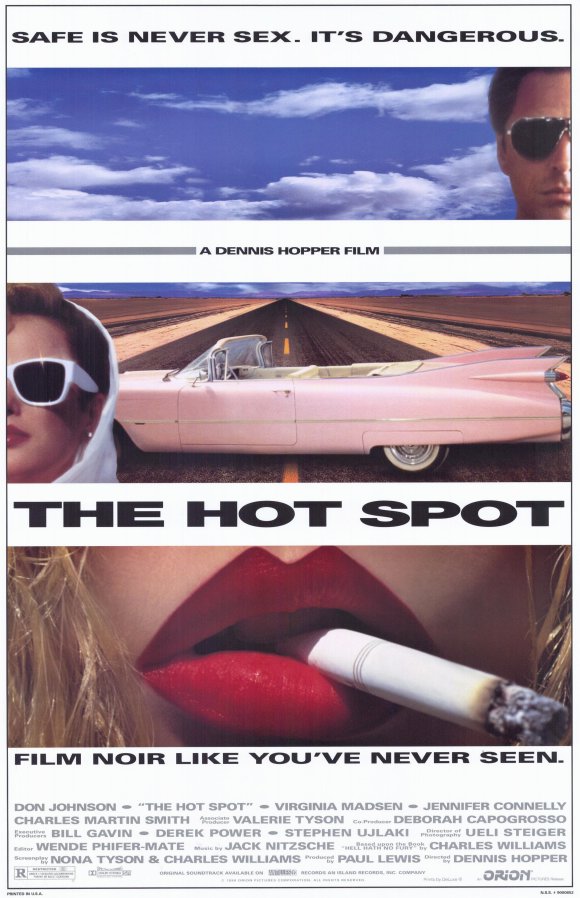

Francois Truffaut once said that it was impossible to pay attention to a film shot in the house where you were born because you’d always be noticing that they wallpapered the bedroom. I knew I was in for the same sort of problem in the opening scene of “The Hot Spot” (opening Friday in Chicago). Dennis Hopper‘s new thriller was made in 1990 but its psychic center is 1957, and Don Johnson, who plays a mysterious stranger from out of town, roars onto the screen in a 1957 Studebaker Golden Hawk.

This is the only car I have ever loved. In 1957, when I was a kid working in a sporting goods store after high school, I’d go next door to the Studebaker dealer and just stand there and look at the car. I felt awe. In “Rain Man,” Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman are driving down the highway in that old Buick, and they pass a ’57 Hawk going in the opposite direction, and Hoffman, the autistic with the steel-trap memory, correctly identifies it. And I shouted out, yes!

And now here is a movie where the hero drives a ’57 Golden Hawk through the entire picture. And here is Dennis Hopper, talking to me about his movie, telling me the screenplay was originally written for Robert Mitchum, back in the 1960s. Somehow it’s almost as well that Mitchum didn’t make the film. A movie containing both Mitchum, the central icon of film noir, and the Golden Hawk, the most beautiful American production sports car since World War II, would have encompassed more than any one film could safely contain. It would have been perfect. I could have stopped going to the movies.

Hopper was up at the Toronto Film Festival for the premiere of his movie, and I walked into the room and asked him flat-out why Don Johnson was driving the ’57 Hawk.

It was a question he did not sound surprised to hear. “Because I like the car,” he said. “I think it’s the best-looking car ever made. It was designed by Raymond Lowey, the same guy that designed the Coke bottle. It’s the greatest-looking car ever made. It really is.

“Why it’s in the movie, is, I put it in. The movie is based on a book called Hell Hath No Fury, written by Charles Williams in 1952. The screenplay was written in 1961 for Robert Mitchum, also by Williams. If you look at the movie, it will appear that it takes place in the present day, because Johnson is a used car salesman and he’s selling recent cars. But I didn’t really change anything, because I didn’t want to. At heart, it’s a film noir from the 1940s or 1950s. I put them all in 1940s-looking clothes. I figured, in a small town in Texas, not a whole hell of a lot has really changed, you know?”

The movie is one of those exercises in style, sex and shadows that were familiar in the postwar years, before high-tech violence came along and took all of the fun out of sin. It’s a sultry melodrama starring Johnson as a man without a past. He drives into town (in the ’57 Hawk) and gets a job in a used car lot by selling a car to a customer even before he’s met the guy who owns the lot. The owner is a slow-thinking fleshapoid with a bum ticker, who lives in a big house up on the hill, where his young and reckless wife (Virginia Madsen) is bored, bored, bored by her endless routine: Get up, slip into a negligee, drink and smoke all day. She needs a real man. The first time she looks at Johnson, she’s like a butcher trying to decide where to make the first cut on a side of prime beef.

Down at the used car lot, Johnson also catches the attention of another girl (Jennifer Connelly), a shy, virginal kid with soft brown hair that floats down to her shoulders, and big brown eyes that blink ever so slowly at the concept of lust. Johnson’s partner at the lot is another salesman (Charles Martin Smith), who somehow senses that Johnson will flash through this job like a meteor, on his way to better things — or death.

The plot involves all the great old noir concepts, such as an evil man who lives in a shack outside of town and knows a dread secret out of the virginal girl’s past, and has on occasion been the lover of the bored car dealer’s wife. It also involves a plan to commit the perfect crime by sticking up a bank in broad daylight. And it includes a lot of scenes where women look yearningly at the hero through plate-glass windows, and seem ready to come right through the glass after him, and bleed to death if that’s what it takes.

“Virginia Madsen drives an old car, too,” I observed. “A ’58 Cadillac.”

“Yeah, right,” Hopper said, “and there’s a scene that’s not in the picture – I hated to, but I had to cut it out; the movie was running four hours – a scene where he first comes into town, and they drive past each other, and slow down, and look at each other’s cars, and she flicks her cigarette at him and drives off, and he almost runs into a truck that’s backing out.”

Madsen plays the Lana Turner type.

“Yeah, exactly. Lana Turner is just what I had in mind. Of all the young actresses, she’s the only one who has that kind of style. That ’40s movie star kind of quality. She has it. And Jennifer Connelly, the young girl, she has a different style. It’s almost invisible acting. She doesn’t push but she’s there. I hate to compare her to Montgomery Clift, but it’s there, that simplicity.”

Hopper is holding court now, enjoying the sound of his words. He has the air of a man who has triumphed over great adversity, as indeed he had. He is eight years clean and sober, after hitting a bottom so hard that he actually spent some time locked up in the proverbial rubber room. We’ve talked about that before. Since then, he has enjoyed a career renaissance that leaves you almost breathless, wondering what he might have accomplished if he hadn’t spent those years of oblivion.

His first career – his first lifetime, really – was as an actor of alienation in movies like “Rebel Without a Cause” (1955). He played the kid in a lot of Westerns (how many people know he was in “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” and “True Grit“?). In 1968, he single-handedly ushered in the whole era of low-budget “youth pictures” with the great success of “Easy Rider.” He was here and there in the 1970s, often playing the spaced-out character he had become, in movies like Francis Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” and Henry Jaglom’s “Tracks.” Then came the lost years, followed by his comeback in 1980 as the director of “Out of the Blue.” As an actor, he has been unceasingly busy, starring in movies such as “Blue Velvet,” “Hoosiers,” “River's Edge,” “Black Widow” and the recent “Flashback,” in which he played a 1960s survivor. His career as a director resumed with “Colors,” the 1988 Sean Penn cop drama, and now here is “The Hot Spot.” And that’s not all. People magazine likes to run cover lines like, “He’s back with a new film, a new wife and a new baby!” And in Hopper’s case, that’s true.

Anyone who grew up as Hopper did, in the late 1940s and 1950s, knows the feeling of a film noir inside out. The key element in many of those movies, I think, is the tension between the bland Middle Americans in the supporting roles and the potential for evil in the leading characters. In a time when everyone conformed, the man who was willing to break the rules was sensed as a danger, even if he never acted on his impulse.

Perhaps Hopper thought he could find that old film noir innocence if he set his film in the little town of Taylor, Texas. To a degree, he does. To another degree, he simply pretends it is still 1951 and the values are all the same, no matter how new the cars are that Don Johnson is selling.

“Orion Pictures brought me this project to see if I might be interested in directing it,” Hopper said. “I read the script, and I thought, `Yeah, I can make a movie out of this.’ I gave it to Paul Lewis, my partner, who works with me on everything. We’ve been together since `Easy Rider.’ He read it and told me there was a 1961 script based on the same book, and it was a much better script then. I said, `Don’t tell me better script. This is a go project. I can make a good movie out of this.’ He said, `Well, OK, but I’m telling you there’s a better script.’

“It turned out Paul had broken the script down for Mitchum in 1961. He knew all about the project, but it was never made. And when they rewrote and updated the script last year, they decided they would take this guy with no past and do the one thing they should never have tried to do, and that is to give him a history. There’s a flashback where we learn the reason he robs the bank is because when he was a kid, the bad banker came and took the farm away from the father. Well, finally Paul got me to read the original 1961 script, and he was right. It was better. So we decided to talk Orion into junking the new script and doing the old script while we were already actually on location.”

So what we have here, in a sense, is a movie in a time warp: A 1961 film noir for Robert Mitchum, made in 1990 with Don Johnson. Not that Don Johnson on his best day will ever be a match for Robert Mitchum, but of course on the other hand we do have the bonus of the ’57 Hawk. And Virginia Madsen could have held her own against any film noir heroine in the book.

Hopper’s direction is clean and economical in the movie, most of the time, and then he breaks out occasionally into tricky moments with light and shadow.

“I do very simple sorts of things,” he said. “My films are all shot at eye level. I have one scene where the camera goes up at the car lot, but it’s like a joke thing. It rises up when he’s proving he can sell a car. Usually it’s all eye level stuff. There’s no tricky fun or weird shots or stuff. I’m not doing Orson Welles. I keep it simple. The only thing I do that most directors don’t do is, I use the Steadicam a lot, so the cameraman can walk around and follow the action. I do masters, closeups, over the shoulders, and it’s simple style. I’m back with John Ford and (John) Huston and (Howard) Hawks – and (Henry) Hathaway; I learned a lot from Hathaway when I was acting in `The Sons of Katie Elder.’ ”

That’s a nice shot, I said, from inside the cabin. While the violence is taking place, we see headlights through two different windows, lighting the acting first one way and then another.

“I work things out at the moment,” Hopper said. “I block the scene, and then I become the camera, and I move all through the scene, and then I show the Steadicam guy my movements. I’m a very visual person. I also walk through all the actors’ parts. I just feel on my feet, how it can be shot.”

Are you still basically an actor, or are you becoming more of a director?

“The ideal would be to direct a movie, and then act in a movie, back and forth, but that’s pretty difficult. I love acting. I really love it. It’s really relatively easy for me now, even the most complex roles, but directing is lot of work. In the fear of not being allowed to direct, I will probably push the acting away, because right now I really want to direct. I feel that I’ve wasted so much time, that I should have made more films.”

You’ve gone through this personal renaissance since you got out of the rubber room, I said. It sounded brutal but we knew what I meant. Did you ever read a poem by Raymond Carver, called “Gravy”? Carver was a guy whose whole career was concentrated in the last 10 years of his life. He was completely unknown until then, a drunk, and then he sobered up and became this great short-story writer. He was supposed to die 10 years earlier, so he called those 10 years “gravy.”

“It fits the way I feel,” Hopper said. “It’s amazing. I was looking out of the plane on the way here today thinking. I was thinking I had no life or any memory really until now. I mean it’s amazing, and every day it gets better. But there’s always this fear of not being able to make the films, not being able to do the work, because it’s inherent in the profession that maybe you’re not going to be able to work anymore. I don’t think anybody, no matter how successful they get, ever loses that fear. If you’ve ever had a period of time, where you weren’t allowed to direct – maybe because you were doing drugs and alcohol, but you didn’t know that was their reason – then the fear is always with you.”