This message came to me from a reader named Peter Svensland. He and a friend have been debating about my qualities as a film critic, and they’ve involved a considerable critic, Dan Schneider, in their discussion. I will say that he has given the question a surprising amount of thought and attention over the years, and may well be correct in some aspects. What his analysis gives me is a renewed respect and curiosity about his own work.

This message came to me from a reader named Peter Svensland. He and a friend have been debating about my qualities as a film critic, and they’ve involved a considerable critic, Dan Schneider, in their discussion. I will say that he has given the question a surprising amount of thought and attention over the years, and may well be correct in some aspects. What his analysis gives me is a renewed respect and curiosity about his own work.

Dear Roger,

A friend and I would like to have your opinion. It’s basically so that we can settle an argument (and small side bet) with a friend over what your opinion would be. My friend and I have carefully co-drafted this email to try to eliminate one or the other of our biases. I hope we succeeded!

I have read your columns and watched your tv shows for many years now and have also enjoyed the few commentaries you’ve done on DVDs. Until now I have always been what is called a “lurker” on blogs; whether yours or other blogs on politics or the arts. Having said that, I want to admit that I usually preferred your old partner Gene Siskel’s opinions to yours. When you guys disagreed I probably sided with his opinion 80-90% of the time. But I always enjoyed your opinions even if I disagreed with them.

One of the things I have enjoyed about your love of films is your charity. I love how you will go out of the way to promote films you believe in (small budget and independent), and also people you support. I recall your championing of Barbara Kopple’s documentary about coal miners, and also how you promoted the Internet film reviewer James Berardinelli. Because of you I started reading his website on a fairly regular basis.

A friend of mine then pointed me to an interview Berardinelli did on film, where you were mentioned. It is a website called www.cosmoetica.com. It is run by a man named Dan Schneider. It is not specifically a film review site, as it has other pieces on literature, poetry, science, and the interview series Berardinelli was in. I have to say that, after reading the Berardinelli interview, I started reading the site (mostly the film stuff) and found it to be quite interesting. I tended to find myself agreeing more with Schneider’s opinions on films more than other critics. In fact, like with Gene Siskel, probably 80-90% of the time. It turns out that his website is quite popular and he seems to be quite controversial because he takes on the opinions of other critics, including you. He is rather scathing of Cahiers du Cinema, Andre Bazin, and many mainstream critics.

This is where my friend and I disagreed. He started comparing Schneider to the film critic Armond White. I looked back at your rip on White, earlier this year, and while I generally agree with your take on him, I think Schneider is a different kettle of fish. Whereas White seems to willfully disagree on the worth of a film merely to stand out, Schneider seems to have interesting rationales for his beliefs. Even when I disagree with his opinions (10-20% of the time) I have to admit he is logical and consistent, even if I think wrong. Therefore I argued that Schneider is not a willful contrarian like White, just someone who brings a different and unique perspective on films.

Then we got to arguing over his opinion of you. My friend is an unadulterated fan of yours; to a fault, I think. While I am a fan of your writing and career, as I mentioned, I think I preferred Siskel to you because he was more cerebral and you were more swayed by emotion. I think Schneider is more like Siskel, as well.

Then we argued over Schneider’s opinion of you. My friend thinks Schneider is very unfair in some of his criticisms of your career. But, I challenged him to look over the times he mentions you or your opinion about a certain film and we found 14 mentions. After some discussion we concluded that in the 14 mentions of you we could find on his website, Schneider was critical of you 6 times, defended your opinion or writing 6 times, and was in the middle twice. In essence, we settled nothing. It was a draw.

If I could sum up Schneider’s opinion of you it would be that, like me, he thinks you are too emotional. He feels you have a mediocre critical ability but are great with words. He feels you won your Pulitzer Prize for your writing not your critical ability. He also feels that you are a great film historian and one of the best DVD commentarians (is that a word?) going. I think you are a bit better critically, but basically I agree with the overall assessment. My friend thinks that any criticism of you has to be based upon envy because you write for a big newspaper and not online.

So, this is why we crafted this letter and I am emailing it. I believe that while you may bristle at some of the caustic criticisms, generally you will think they are rational, and not based in spite or the contrarianism of Armond White. My friend thinks any disagreement with your opinion is tantamount to a diss.

So, we decided to send you the links and pertinent comments, and let you decide. A steak dinner is riding on your decision!

First, the two middle of the road comments by Schneider:

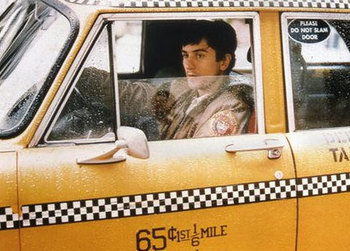

Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver“

Roger Ebert is perhaps the most famous film critic in America. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his writing. It should be noted, however, that that award was for the writing, not his analytical skills. What separates Ebert from most published critics is that he is better with words than most. A dozen or more of his reviews are classics whose words stick with me to this day, such as his review of Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver“, which ends this way:

“Taxi Driver” is a hell, from the opening shot of a cab emerging from stygian clouds of steam to the climactic killing scene in which the camera finally looks straight down. Scorsese wanted to look away from Travis’s rejection; we almost want to look away from his life. But he’s there, all right, and he’s suffering.”

This is a terrific piece of writing. Yet, Ebert is notoriously dense. He thinks that Steven Spielberg is a great filmmaker, and has panned many great films while praising schlock from the above mentioned hack, as well as the “Star Wars” films, and many other Hollywood junk fare, even as he recognizes, say, both the greatness and cultural relevance of the “Up Series” of Michael Apted. In short, his longtime partner, Gene Siskel, who never quite had Ebert’s way with words, nonetheless understood the art of film far more deeply, and, while not a better writer, was certainly a better critic.

Errol Morris’s “Gates of Heaven“

Schneider’s review of “Gates of Heaven.”

This fatal shortcoming is nowhere more evident than in Ebert’s infamous DVD blurb about Errol Morris’s 1978 documentary about pet cemeteries, “Gates of Heaven” (not to be confused with Michael Cimino’s monumental Western film flop “Heaven's Gate“), which declares this film one of the top ten films of all time. Not one of the top ten documentaries of all time, but films! Hell, it’s not even close to being as good a film nor documentary as Morris’s later “The Thin Blue Line” nor “The Fog of War.” Perhaps this was just a young critic trying to make his mark. But, the evidence for Ebert’s making outrageously dumb proclamations is long. One might argue this is a solid to good documentary, and that it even is an important one, for its portrait of weirdos unleashed a flood of documentaries, in the near three decades since, about losers, wackos, and society’s castoffs, as if there was some great significance to cultural failure.

Oliver Hirschbiegel’s “Downfall“

Schneider’s review of “Downfall.”

Critic-at-large, Roger Ebert, rightly took Denby to task for his puerility, stating, “I do not feel the film provides ‘a sufficient response’ to what Hitler actually did,’ because I feel no film can, and no response would be sufficient.” But, after such a concise summation, he then adds, of Hitler, “He was skilled in the ways he exploited that feeling, and surrounded himself by gifted strategists and propagandists, but he was not a great man, simply one armed by fate to unleash unimaginable evil.”

This is a remark clearly mindful of Louis Farrakhan’s claims, a few years back, that Hitler was a “great man,” that unleashed a firestorm, but it is also logically self-defeating, and shows that Ebert is not only not a student of history, but much better in phrasing words than thinking out their logical consequences. Hitler did not merely waltz onto the world stage, and have everything fall into his la-p- from admirers to world events. He had a precise blueprint, aka Mein Kampf, worked for years perfecting his “craft,” demagoguery, and actively shaped his future. He came within two or three bad decisions of wiping out Eurasian Jewry, and even more minorities, as well as the colonial powers of Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Like it or not, Hitler was a great man, as were Stalin and Mao, and Genghis Khan and Alexander the Great before them. Mass murderers all, but all great, as long as one is mindful that great does not only mean ‘good’ nor ‘decent,’ and that great men also can have great flaws.

Now, the six positive comments:

Alex Proyas’s “Dark City“

Schneider’s review of “Dark City.”

Film critic Roger Ebert, who is often oblivious to narrative pluses and minuses, is well known for having declared “Dark City” 1998’s best film. I would likely give that to Terrence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line” (at least for American releases), but he is correct when he notes the influence of American painter Edward Hopper on the film, as well as this observation: “Notice an opening shot that approaches the hotel window behind which we meet Murdoch. The window is a circular dome in a rectangular frame. As clearly as possible, it looks like the ‘face’ of Hal 9000 in 2001. Hal was a computer that understood everything, except what it was to be human and have emotions. “Dark City” considers the same theme in a film that creates a completely artificial world in which humans teach themselves to be themselves.”

The shot may not be a direct quotation from the Kubrick masterpiece, but it does echo my earlier claim that both this film and The Strangers are thoroughly drenched in the cinema of the 20th Century, and seem to have recreated the city in their idée fixee of cinema realities past.

Samuel Fuller’s “The Big Red One“

Schneider’s review of “The Big Red One: The Reconstruction.”

Yet, this film is not supposed to be about war, itself, as a subject, but the men who fight those wars. All great films focus on characterization, even if obliquely. It’s why a film like “Saving Private Ryan” fails, and this one succeeds brilliantly. In ending his review of the original film’s release in 1980, film critic Roger Ebert wrote:

“While this is an expensive epic, he hasn’t fallen to the temptations of the epic form. He doesn’t give us a lot of phony meaning, as if to justify the scope of the production. There aren’t a lot of deep, significant speeches. In the ways that count, “The Big Red One” is still a B-movie — hard-boiled, filled with action, held together by male camaraderie, directed with a lean economy of action. It’s one of the most expensive B-pictures ever made, and I think that helps it fit the subject. A war movies are about War, but B war movies are about soldiers.”

In many ways, Ebert is correct, at least about the original film. But, in the restored version we do get some speechifying, especially by the lone main German character, Sergeant Schroeder (Siegfried Rauch), who shadows Marvin’s character throughout the war. It’s a key role that was butchered in the original, but serves a vital purpose in humanizing the enemy in any war. We learn much about the German sergeant in his small scenes, and while he is not likable, he is certainly explicable.

Michael Apted’s “The Up Series”

Schneider’s review of “The Up Series.”.

It is a rare synchronicity that finds me in agreement with American pop film critic Roger Ebert. Usually, he shows no real understanding of the role good writing plays in filmmaking, and routinely praises the use of clichés, such as the tripe of Steven Spielberg and other Hollywood fare. However, when he declared The Up Series of documentary films, by Michael Apted, now out on DVD, “an inspired, almost noble use of the film medium, Apted penetrates to the central mystery of life,” I not only concur, but almost forgive him for recommending “Saving Private Ryan.” I said almost, now.

“Yosihiro Ozu’s “Story of Floating Weeds” and “Floating Weeds“

Schneider’s review of Ozu’s two “Floating Weeds” films..

…the commentary for “Floating Weeds,” by famed film critic Roger Ebert, by contrast, is outstanding, and far better. Ebert’s years in front of a television camera have taught him how to perfect a conversational tone so that you feel he’s whispering into your ear at a movie theater. He is knowledgeable, with a broader knowledge of film, in general, than Richie, and never gets too discursive nor too far afield from what is in front of the viewer. He also eschews the fellatric sort of commentary that too many film stars and filmmakers reflexively fall into. Were his actual written film reviews as incisive as his commentaries on the DVDs (such as “Citizen Kane” or “Dark City“) he has done, he would rank as the top published film critic around, not merely the most famous. Unlike Richie, Ebert never delves in to masturbatory film school minutia nor theory. Instead, he debunks much of it that Ozu’s work embodies the opposite of, and talks about Ozu’s use of “pillow shots,” which, as mentioned, are stylistically beautiful shots that do not advance a story, but merely allow the viewer a moment’s aesthetic rest between the dramatic situations. This contrasts greatly with the Hollywood obsession with having merely everything advance the action of the film.

Alan J. Pakula’s “All the President’s Men“

Schneider’s review of “All the President's Men.”

Roger Ebert, the famed film critic, probably framed the film’s problem best when he wrote:

“All the President’s Men” is truer to the craft of journalism than to the art of storytelling, and that’s its problem. The movie is as accurate about the processes used by investigative reporters as we have any right to expect, and yet process finally overwhelms narrative- -we’re adrift in a sea of names, dates, telephone numbers, coincidences, lucky breaks, false leads, dogged footwork, denials, evasions, and sometimes even the truth….yet they don’t quite add up to a satisfying movie experience. Once we’ve seen one cycle of investigative reporting, once Woodward and Bernstein have cracked the first wall separating the break-in from the White House, we understand the movie’s method. We don’t need to see the reporting cycle repeated several more times just because the story grows longer and the sources more important. For all of its technical skill, the movie essentially shows us the same journalistic process several times as it leads closer and closer to an end we already know. The film is long, and would be dull if it weren’t for the wizardry of Pakula, his actors, and technicians. What saves it isn’t the power of narrative, but the success of technique.”

Exactly. The real stars of the film are not Redford and Hoffman, but its music editor- David Shire, film editor, Robert L. Wolfe, but most especially its cinematographer, the great Gordon Willis.

John Boorman’s “Deliverance“

Schneider’s review of “Deliverance.”

Many strains of its themes can be seen in other “river” films as diverse as “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” “Apocalypse Now,” “Stand By Me,” “A River Runs Through It“, and “Mean Creek.” With the exception of the last film (a teen version of “Deliverance“), all of the rest of the films avoid propulsion by the Dumbest Possible Action. That so few critics, then or now, recognized this fact is typical. I was ready to say amazing or appalling, but who am I kidding? It would have been amazing had more recognized what a crock the film serves up. One of the few that did, surprisingly, was the Chicago Sun-Times’ often stolid film critic Roger Ebert, who wrote:

“Dickey, who wrote the original novel and the screenplay, lards this plot with a lot of significance–universal, local, whatever happens to be on the market. He is clearly under the impression that he is telling us something about the nature of man, and particularly civilized man’s ability to survive primitive challenges….But I don’t think it works that way….What the movie totally fails at, however, is its attempt to make some kind of significant statement about its action….Dickey has given us here is a fantasy about violence, not a realistic consideration of it. It’s possible to consider civilized men in a confrontation with the wilderness without throwing in rapes, cowboy-and-Indian stunts and pure exploitative sensationalism.”

Exactly. Ebert does not mention the Dumbest Possible Action trope because the term had yet to be coined, but the film is pure fantasy.

Finally, the six negative comments:

Woody Allen‘s “Stardust Memories“

Schneider’s review of “Stardust Memories“.

“The movie begins by acknowledging its sources of visual inspiration. We see a claustrophobic Allen trapped in a railroad car (that’s from the opening of “8 1/2,” with Marcello Mastroianni trapped in an auto), and the harsh black-and-white lighting and the ticking of a clock on the sound track give us a cross-reference to the nightmare that opens Ingmar Bergman’s “Wild Strawberries.” Are these the exact scenes Allen had in mind? Probably, but no matter; he clearly intends “Stardust Memories” to be his “8 1/2“, and it develops as a portrait of the artist’s complaints.”

This paragraph opens Ebert’s review, and in it he already summarizes the gripes I mention, and negatively biases an astute film lover against the film. While the reference to the Fellini opening is apt, the Bergman comparison is not, as the scenes do not match up. It’s about as apt as comparing any sci-fi space opera’s shots of a spaceship cruising along as an homage to the scene in “2001: A Space Odyssey” where we first see the ship Discovery One. It’s a generic comparison that aims to imply that there is nothing original in the scene, and doubly so. Then we get Ebert’s further linkage of Allen’s films with the overarching posit of Fellini’s film, as “a portrait of the artist’s complaints.” Yet, as the film progresses, we see that Allen’s film is nothing like that. In fact, whereas Fellini’s film ends resignedly, with life never able to equal art, Allen’s film ends utterly positively, portraying the total triumph of art over life, in its ability to supplement and better it.

Ebert then claims the film is yet another reworking of Allen’s relationships with women, as earlier films like “Annie Hall” and “Manhattan” were, but he does not see that this is only superficially so. “Stardust Memories” uses the main character’s sexual relations merely as a device to propel a deeper introspection that his earlier films barely touch upon. Ebert writes:

“The subjects blend into the basic complaint of the Woody Allen persona we have come to know and love, and can be summarized briefly: If I’m so famous and brilliant and everybody loves me, then why doesn’t anybody in particular love me?”

Yet, the main character has love and adulation aplenty, both in private and public, so Ebert is really missing out on the very antithesis of this film’s essence–which is the art– and what it can lead to, not the things it can bring: love, sex, fame, etc.

Then Ebert goes on into an astonishing misreading of the film:

“At the film seminar, the Allen character is constantly besieged by groupies. They come in all styles: pathetic young girls who want to sleep with him, fans who want his autograph, weekend culture vultures, and people who spend all their time at one event promoting the next one they’re attending. Allen makes his point early, by shooting these unfortunate creatures in close-up with a wide-angle lens that makes them all look like Martians with big noses. They add up to a nightmare, a nonstop invasion of privacy, a shrill chorus of people whose praise for the artist is really a call for attention. Fine, except what else does Allen have to say about them? Nothing. In the Fellini film, the director-hero was surrounded by sycophants, business associates, would-be collaborators, wives, mistresses, old friends, all of whom made calls on his humanity. In the Allen picture, there’s no depth, no personal context: They’re only making calls on his time.”

Well, this is true, only to an extent, and the reason for it is thus: the lead in the Fellini film (Marcello Mastroianni) was a damaged and unwhole individual, whereas the lead in the Allen film (Allen) is not. It is all the other people, about him, who are leeching off of him precisely because he “has it together” and they do not. In other words, Ebert simply does not like the situation Allen presents because he sees a superficial resemblance to the Fellini film, and is unable to grasp that Allen’s aim is not a repetition of Fellini’s, but a subversion of it, while going well beyond it. Mastroianni’s character’s friends do make calls on his humanity, but because the film clearly shows it’s an area the character may be lacking in–for he his a definite narcissist and a borderline sociopath. The Allen character is neither of these things. He is a great artist within the world of Allen’s film, evidenced by the snippets of that character’s films we see, whereas the bits of the Mastroianni character’s films we see are clearly something which makes one question is that character really still ‘has it.’

Ebert’s ‘analysis’ then totally derails, likely because of his utter misreading of the film because he did not get, or, more likely, did not “like” its aims:

“What’s more, the Fellini character was at least trying to create something, to harass his badgered brain into some feeble act of thought. But the Allen character expresses only impotence, despair, uncertainty, discouragement. All through the film, Allen keeps talking about diseases, catastrophes, bad luck that befalls even the most successful. Yes, but that’s what artists are for: to hurl their imagination, joy, and conviction into the silent maw. Sorry if I got a little carried away.”

First, the Allen character is trying to create a film–the one that opens “Stardust Memories,” and it seems a good one. His main interior angst, as a character, is that studio heads take the film away and butcher it. We see his creation goes well beyond the Mastroianni character’s, yet Ebert’s total lack of mentioning this is odd. Well, not really, since, as we read earlier, he sees the whole arc and point of the film as a rehash of earlier Allen works: “The basic complaint of the Woody Allen persona we have come to know and love, and can be summarized briefly: If I’m so famous and brilliant and everybody loves me, then why doesn’t anybody in particular love me?”

So, if Ebert cannot even get that correct, is it any wonder that he, and many even lesser critics, so totally botched their critiques of this great film? And, Ebert shows he has a basic and fundamental misunderstanding of what art is and what purpose it serves when he writes: “but that’s what artists are for: to hurl their imagination, joy, and conviction into the silent maw.” Not even his apology can excuse Ebert’s blunder. Art merely illumines the wisdom of life by condensing it from ponderous philosophy into forms that are simultaneously more accessible to the more intuitively intellectual aspects of the mind, while achieving this via satisfying the emotional aspects of the self that desire entertainment. Ebert’s definition buys into the Joseph Campbellian Heroic Artist Hokum that has long been disproved.

Ebert continues:

“Stardust Memories” inspires that kind of frustration, though, because it’s the first Woody Allen film in which impotence has become the situation rather than the problem. This is a movie about a guy who has given up.”

Apparently he did not watch the last two minutes of the film which totally and utterly subverts Ebert’s claim, which, itself, is based on the fallacy that the film depicts impotence–yet another example of Ebert trying to link the film to earlier film’s in the Allen canon, but without any rationale for it, save his own misreading.

He ends his review thus:

“Stardust Memories” is a disappointment. It needs some larger idea, some sort of organizing force, to pull together all these scenes of bitching and moaning, and make them lead somewhere.”

As stated, the larger idea is utterly missed by Ebert, because he commits the one fundamental flaw of criticism from which there is no recovery nor pardon: he has reviewed not the work of art that the artist has presented, but a work of art that the critic has hoped that the artist has presented, thus finding flaws not in the art itself, but in what the art is not. It is like criticizing an elephant for not having a long neck like a giraffe because the zoo guide went from the giraffe cage to the elephant cage, and told the zoogoers that the elephant was the larger animal, meaning in mass, whereas the critic took it “larger” to mean simply “taller.” As one can easily see, when such a thing occurs, the fault lies not with the zoo guide, nor his words, but with the inapt expectations of the zoogoer. See how difficult it is for great art to emerge when dealing with Lowest Common Denominator expectations and minds?

Michael Curtiz’s “Casablanca“

Schneider’s review of “Casablanca.”

By contrast, the other commentary, by film critic Roger Ebert, is his usual quality commentary. What makes it good is not that Ebert has such insights, for he repeats much of what Behlmer imparts, but he has a love for the film, and scene specific comments that illuminate things a casual viewer might miss. As I’ve stated before, Ebert has serious limitations as a serious critic of film, but he is eminently qualified as a film historian.

The reason for this is because Ebert is too emotionally dependent in his critiques; of the thousands of reviews he’s written, you can certainly point to a few dozen, maybe a hundred or two, that are gems–well written (and, let’s face it, the man won his Pulitzer for his wordsmithing, not his critical skills) and insightful about the film and its aspects. But, the truth is that that is an example of dart tossing. Toss enough darts, even backward, and over your shoulder, and a few bull’s-eyes will emerge. And dart tossing is just randomness, it’s not an intellectual critical facility that’s replicable. When he is detached and objective, Ebert will make a good technical comment about the left to right movement of a scene following Louie and Rick into Rick’s office, when he needs to get money from the safe, and the camera’s eliding a wall that reappears just moments later, even though, in reality, this would be impossible. But, much too often Ebert lets his emotions get the better of him, such as in some inanely embarrassing burblings about Ingrid Bergman, where he focuses on Bergman’s lips, as if they had any bearing on her acting in certain scenes.

The worst (or best) example of Ebert’s emotionalism actually comes from his own mouth, near the end of the commentary, when he discourses on “Casablanca‘s” place in film history. He compares it to “Citizen Kane,” and concludes that the Welles film is the superior work of art, but that “Casablanca” is the superior entertainment (a view which, despite all the disagreements I have with Ebert on this and other films, I share). As a corollary, he attempts to define what a classic film is, and concludes that a classic is a film one could not bear never seeing again. Note, that his definition is a wholly emotional and subjective one. Compare that with the definition of a great film (or any work of art) as something that successfully engages and enriches the mind and aesthetics through the excellence of its construction and/or performance.

Note, that while there is some subjectivity in how well such a thing will affect different individuals, there is an objectivity in the ways the construction and/or performance can be measured. But, Ebert’s biggest sin, in this commentary, aside from his near fetishism over Bergman’s bodily parts, is his constant denigration and misassesment of the acting of Paul Henreid. More than once, Ebert states how he does not “like” the character of Victor Laszlo, and how he “likes” Rick Blaine, despite Victor’s superior resume as a man. These emotionally biased likes and dislikes then lead into Ebert’s assigning character traits and flaws to the two that are simply not in the film, but merely Ebert’s justifications for his biases. Even worse, Ebert admits to not particularly liking the actor, Paul Henreid, although he gives no reasons (although one suspects that he is simply not Humphrey Bogart). This dislike, in turn, leads to equating the stiffness of the character of Victor with the acting performance of Henreid, which, as I have argued and shown, is a false equation. Despite these flaws, though, Ebert’s commentary is significantly better than Behlmer’s.

Theodoros Angelopoulos’ “Ulysses’ Gaze“

Schneider’s review of “Ulysses' Gaze.”

The film came in second at the Cannes Film Festival that year, winning the Grand Prix, not the Palm D’Or, but it has taken a beating from some critics. In this country, the most virulent review came from none other than that noted lover of Spielbergian tripe, Roger Ebert, who among other things, wrote:

“What’s left after ‘Ulysses’ Gaze‘ is the impression of a film made by a director so impressed with the gravity and importance of his theme that he wants to weed out any moviegoers seeking interest, grace, humor, or involvement….It is an old fact about the cinema- known perhaps even to those pioneers who made the ancient footage A is seeking- that a film does not exist unless there is an audience between the projector and the screen. A director, having chosen to work in a mass medium, has a certain duty to that audience. I do not ask that he make it laugh or cry, or even that he entertain it, but he must at least not insult its good will by giving it so little to repay its patience. What arrogance and self-importance this film reveals.”

Would that Ebert was so assertive about the vomit that the many Hollywood schlockmeisters he praises put out. Yes, this film is not a laugh riot, but there are some humorous moments, such as Keitel’s interactions with an old Albanian woman he lets share a Greek cab with him. As for grace, interest, and involvement? Well, it’s there, even if it requires a bit of intellectual cogitation on the part of a viewer, something that most Americans (and American critics) are unwilling to give.

Abbas Kiarostami’s “Taste of Cherry“

Schneider’s review of “Taste of Cherry.”

Even Roger Ebert, whose film criticisms are as scattershot as any critic’s I have ever read, grew tired of Kiarostami’s seeming game playing with the audience:

“….I am not impatiently asking for action or incident. What I do feel, however, is that Kiarostami’s style here is an affectation; the subject matter does not make it necessary, and is not benefited by it. If we’re to feel sympathy for Badhi, wouldn’t it help to know more about him? To know, in fact, anything at all about him? What purpose does it serve to suggest at first he may be a homosexual? (Not what purpose for the audience- what purpose for Badhi himself? Surely he must be aware his intentions are being misinterpreted.) And why must we see Kiarostami’s camera crew- a tiresome distancing strategy to remind us we are seeing a movie? If there is one thing ‘Taste of Cherry‘ does not need, it is such a reminder: The film is such a lifeless drone that we experience it only as a movie.”

While I disagree with Ebert’s overall rejection of the total film, and his claim re: the homosexuality gambit, his anger over the breaking of the fourth wall is justified, as is his claim of affectation, even if I do not feel the film is a lifeless drone. Ebert also disseminates the tale that Kiarostami filmed ‘Taste of Cherry‘ with himself asking non-actors to bury him, thus why we do not see Badii in the same shots with the others. But, this fact is disputed by other critics of the film.

Sam Peckinpah’s “Straw Dogs“

Schneider’s review of “Straw Dogs.”

Even the powerful Roger Ebert muffed his criticism of the film. While he correctly thought it one of Peckinpah’s weaker films, especially in relation to “The Wild Bunch,” his reasons were unfathomable. He wrote: “The most offensive thing about the movie is its hypocrisy; it is totally committed to the pornography of violence, but lays on the moral outrage with a shovel.”

The very thing that sticks out about the film is that it is amoral. The characters are shown doing crazy and violent things and little consequence is shown. That is not hypocrisy, it is anarchy.

Alfred HItchcock’s “Vertigo“

Schneider’s review of “Vertigo.”

In this film’s 1950s universe most problems are solved by taking a swig of alcohol, preferably brandy. Failing that solution, there are quacks who provide the most inane diagnoses possible. When Midge is done visiting the mute Scottie in the asylum, she stops in at his doctor’s office, to see what her ex’s condition is. Is she told anything profound? No, the diagnosis is the manifest sort that any thinking person over the age of twelve could reasonably give. The doctor informs her that Scottie is suffering from that pseudoscientific catchall, melancholia, as well as a guilt complex. Wow, Doc. It took how many years in college to come up with this sort of insight? Then, when Midge tells the doctor that Scottie was also in love with the woman that ‘died’, the doctor’s profound retort is that such a fact ‘complicates the problem.’ I guess he never spoke with his patient, nor even looked into any of the facts surrounding his case? Yet, even a critic as renowned as Roger Ebert wholly misses this huge and fatal flaw in the film, instead rhapsodizing like this:

“There is another element, rarely commented on, that makes ‘Vertigo‘ a great film. From the moment we are let in on the secret, the movie is equally about Judy: her pain, her loss, the trap she’s in. Hitchcock so cleverly manipulates the story that when the two characters climb up that mission tower, we identify with both of them, and fear for both of them, and in a way Judy is less guilty than Scottie.”

Uh….no. Absolutely not. This is like the BS that some critics spew that this film was somehow ‘confessional’, and that Hitchcock was deconstructing his own real or imagined misogyny. Had the audience been left guessing about whether or not Judy was ‘Madeline’, it would have been far more effective. This would have truly pulled the viewer into Scottie’s world–much more so than the visual razzle-dazzle Hitchcock uses to show Scottie recalling ‘Madeline’ when he kisses Judy. Of course, this is assuming we do suspend the disbelief that Judy could ever be such a perfect doppelganger for ‘Madeline’, without actually being her. Once the audience knows that Scottie knows what we do, that he is correct about Judy’s role in his fate, there is no dramatic tension, in the thriller sense, and we can only be left to guess how Judy will get her comeuppance- be it by death or the law.

To end this email, I submit it to you. My friend thinks that Schneider is just another Armond White, that he is a contrarian and merely envious at your financial and public success. I disagree. I think Schneider is hard on you (perhaps a little too hard, although he is much harder on other critics). I also feel that, unlike Armond White, Schneider is consistent (almost maddeningly so) in his logic. He just seems more controversial than White, but when you read him he’s a lot saner and deeper

My friend now refuses to even read Schneider’s opinions, but I think he’s in a snit because Schneider does not revere you as a god. Reading Schneider’s reviews has made me rethink what I know and get from film.

So, we leave it to you. A steak dinner is in the balance. Do you think Schneider is a contrarian Armond White clone or is he more like Gene Siskel, a cerebral critic first and foremost, whereas you are an emotion-first critic?

I suggest you buy one of those big T-bones and share it.

Dan Schneider is observant, smart, and makes every effort to be fair. I would agree that I am a more emotion-driven critic than Siskel or Schneider, and indeed many others. My reviews usually include a reflection of how I felt during a film, since film itself is primarily an emotional, not a cerebral, medium. For example, although like most everybody I found “Triumph of the Will” evil, I also lingered on how boring it was. If you’re not comfortable sitting through a film, what can you easily get from it?

I must say I still agree with my opinions as quoted by Schneider, and I conclude he is more analytical and less visceral that I am. Readers find critics who speak to them. What is remarkable about these many words is that Schneider keeps an open mind, approaches each film afresh, and doesn’t always repeat the same judgments. An ideal critic tries to start over again with every review.

There are three things on which we adamantly disagree. (1) I do not have a broader film knowledge than Donald Richie, and Schneider may be the only person who has ever thought so. (2) I disagree with his dismissal of Spielberg. The man who made “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial” is not a schlockmeister purveying tripe. (3) The third is Ingrid Bergman, and my “burblings” about her lips. A critic who doesn’t acknowledge the role of her face and presence in a “Casablanca” will, I fear, date just about anybody. Our critical differences I leave to you. I invite you to continue your discussion in the Comments below.

In the matter of Ingrid Bergman, I offer the final word to Miss Bergman.

A scene from “Ulysses’ Gaze.”

A scene from “Taste of Cherry“

A scene from “Stardust Memories“

Get the <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/widget/roger-eberts-journal-rebert”>Roger Ebert’s Journal</a> widget and many other <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/”>great free widgets</a> at <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com”>Widgetbox</a>! Not seeing a widget? (<a href=”http://docs.widgetbox.com/using-widgets/installing-widgets/why-cant-i-see-my-widget/”>More info</a>)